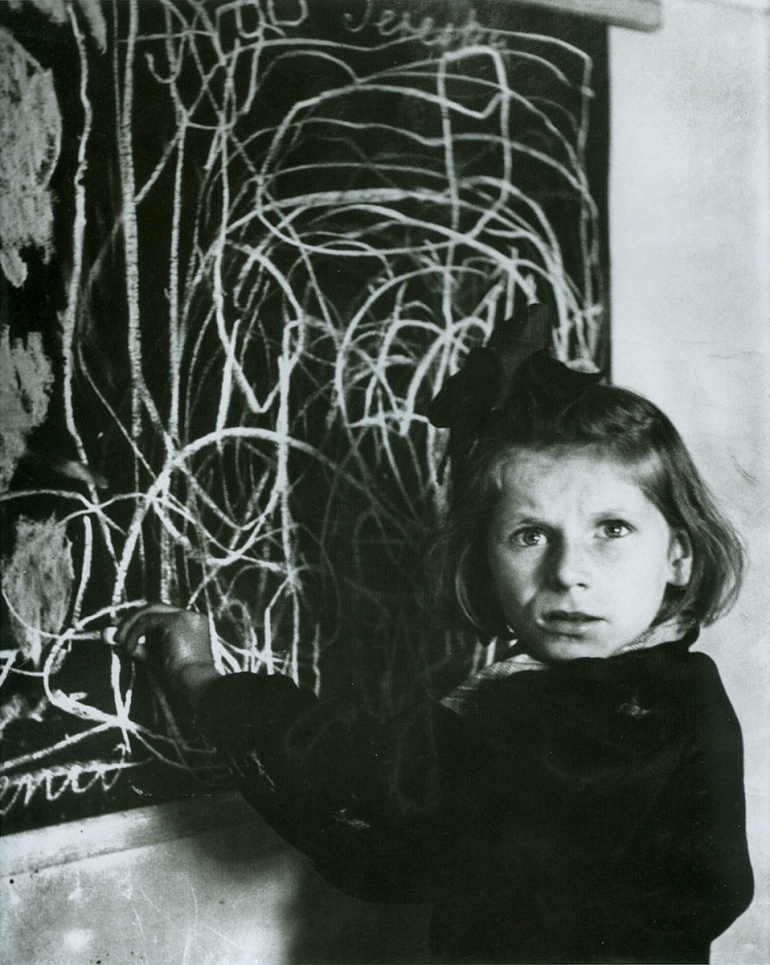

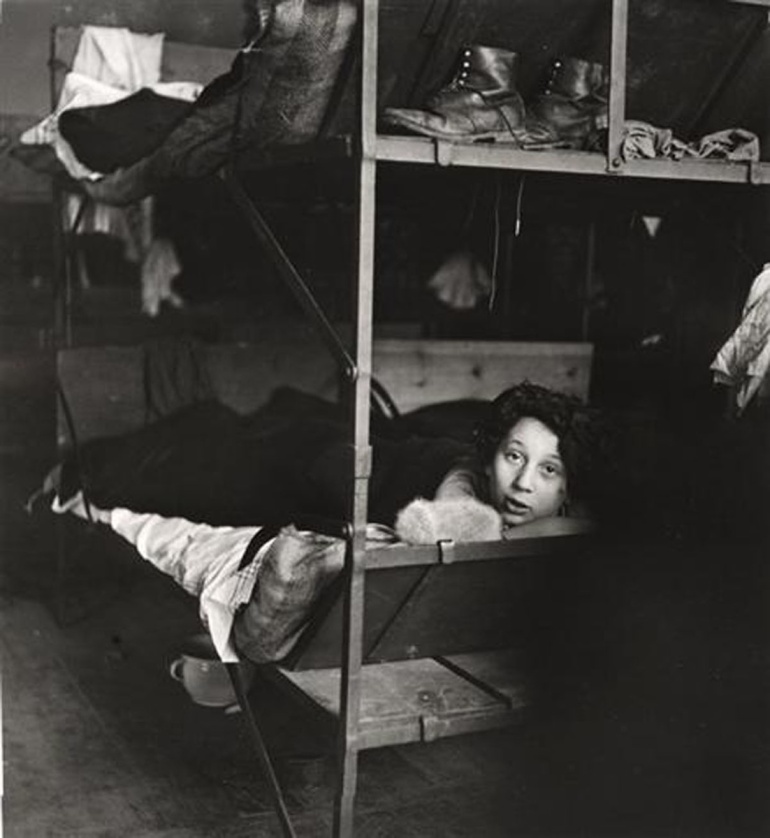

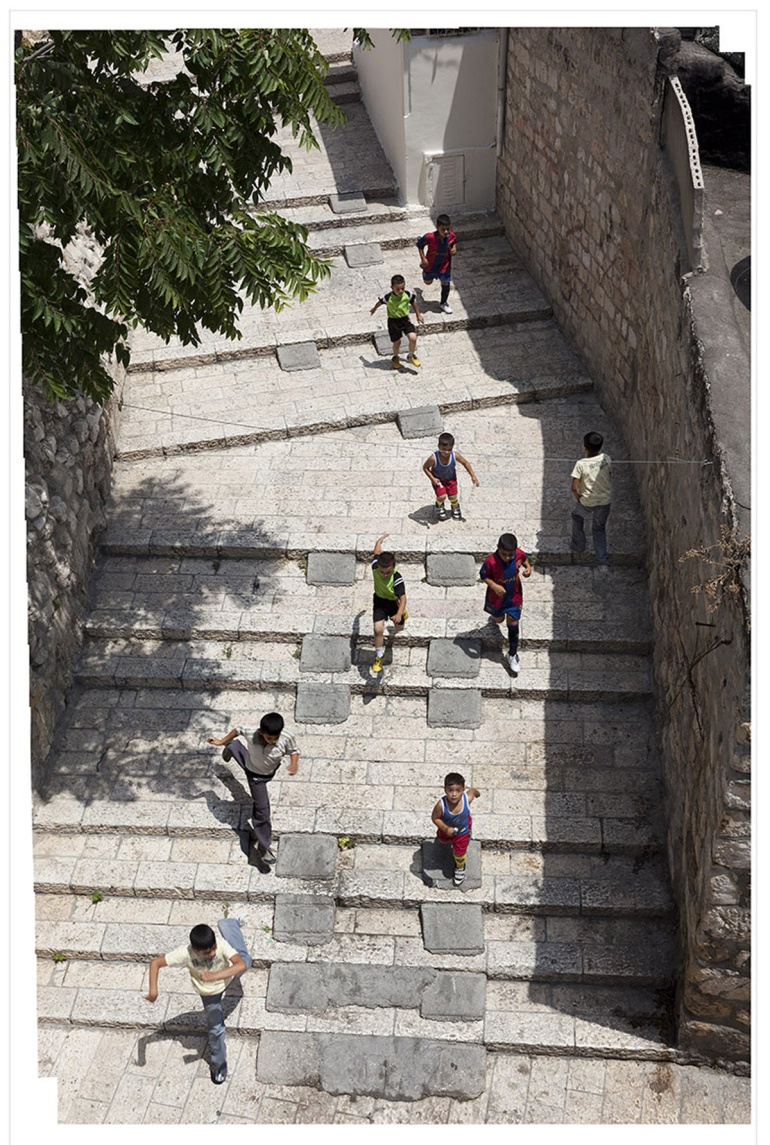

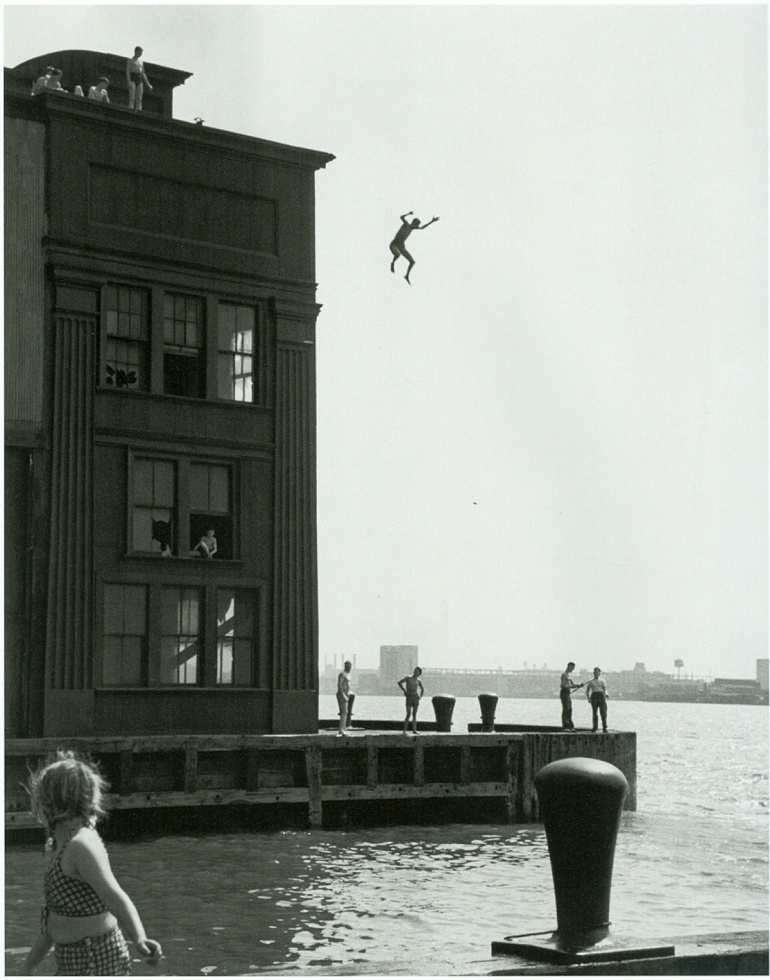

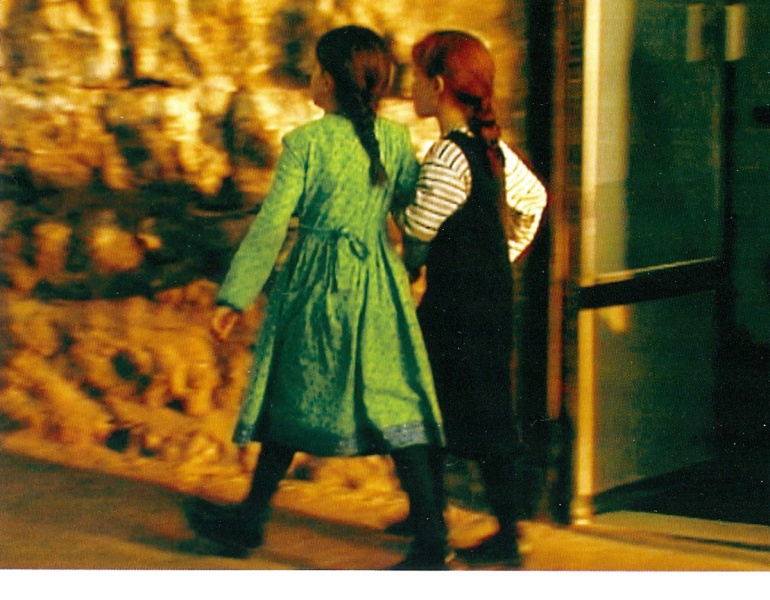

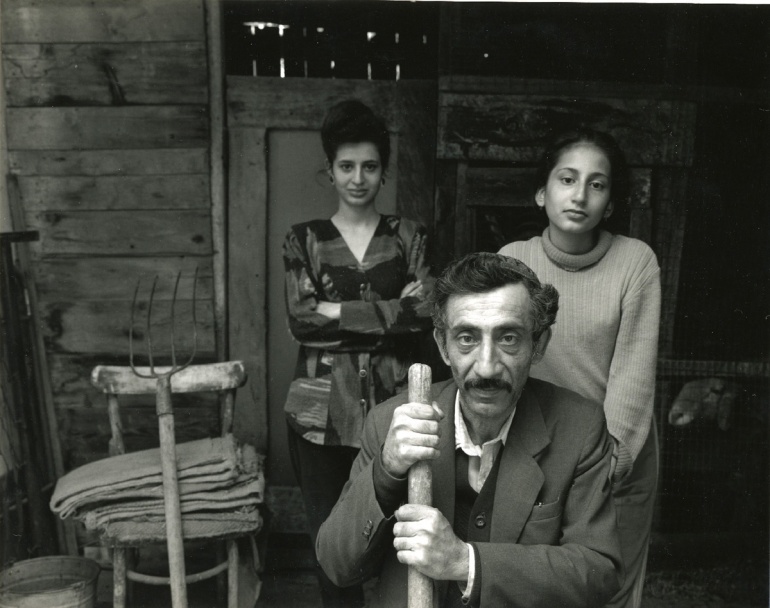

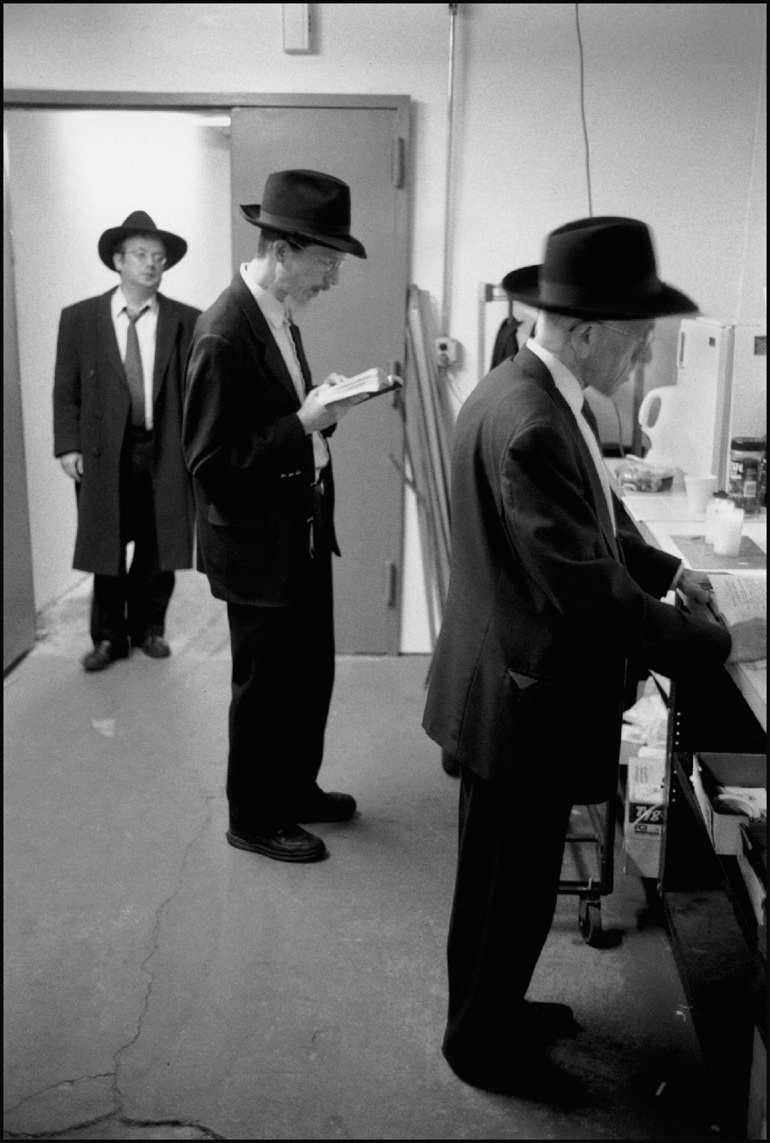

We Went Back: Photographs from Europe 1933-1956 by CHIM

Two masters of modern photography are on view at the International Center of Photography; Chim (Szymin); aka David Seymour and Roman Vishniac. They are both Jewish and just happen to bring astute but radically different visions…