Why Pictures?

Most Hebrew books have no pictures. Nobody misses them. In fact most books have no pictures, Hebrew or otherwise. The authority of the text is more than sufficient to communicate the ideas, sensations and emotions that literature specializes in. Picture books are ultimately different. The presence of pictures can serve to decorate, illustrate, elaborate, comment or perhaps contradict the adjoining text, thereby making picture books potentially much more complex because of the constant interchange between text and visual, both of which clamor for our attention. So the question arises why should certain Hebrew books have pictures… i.e. what is accomplished?

Supreme Hebrew Printed Books, on exhibition June 17, 18 and 20th, followed by an auction at Kestenbaum & Company, offers some answers. This collection of 86 books and documents pays special attention to rare books printed in the 16th – 18th century with a supplement of an equally important selection of Americana, including Hayyim Isaac Carigal’s (a well known rabbi from Hebron) “Sermon Preached at (Touro) Synagogue, Newport, Rhode Island” for Shavous in 1773.

The wide ranging European selection includes a rare Constantinople 1509 edition of the Mishneh Torah (valued at close to $100,000), a 1540 Constantinople edition of Jacob ben Asher’s Arba’ah Turim, two 1768 books written and printed by Jacob Emden and a 1569 first edition from Cracow of the first halachic work by the Rem’a. Also on view is the first printed edition of Shimon ben Yochai’s Sefer Ha Zohar from Mantua, 1560 and two first editions of Ovadiah Sforno’s commentary on the Torah printed in Venice. The scope of the Kestenbaum exhibition is truly breathtaking.

In the midst of this cacophony of masterpieces is an illustrated gem, the renowned Meshal ha-Kadmoni (Fable of the Ancient) by Isaac ibn Sahula, (touted in the Kestenbaum catalogue as “The illustrated Hebrew book par excellence”). While that designation might be challenged, this small volume hosts eighty woodcut illustrations that supplement and enlarge the text of the 13th century collection of animal fables. The book takes the form of a dialogue written in rhymed prose (known as maqama, a form popular in contemporary Castilian Islamic culture) that addressed an educated and sophisticated Jewish audience of youth, lay adults and women readers.

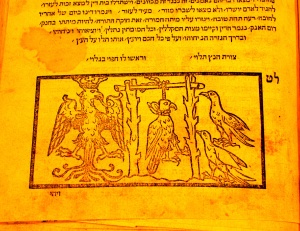

The question on the tip of our tongues is of course, what do the pictures add? Considering the extremely erudite nature of this text, a sophisticated entertainment laced with Biblical, Talmudic and Halachic quotations, it is highly unlikely that the pictures were meant as illustrations for illiterate readers. Rather they add nuance to the allegories by fixing some of the concepts in concrete visual form. A case in point is the depiction of the eagle (nesher) seated on his royal throne while his Sanhedrin of birds accuses the crow of murdering other birds. No bird comes to testify in on the crow’s behalf and he is condemned to death by hanging, which is tellingly illustrated. The halachic details of courts of law, witnesses and judgment are all presented in the form of a fable of the birds even as the illustrations snap the concepts into a kind of alternative reality. The hanging crow, looking almost absurd, framed by two bird witnesses on one side and the kingly eagle on the other vividly encapsulates the allegory. At the same time the image is intensely memorable because of the inherent absurdity of animals acting like humans. It becomes a lesson visually fleshed out in a timeless reality, confirming the very substance of the allegorical mode. There are other illustrations that utilize humans in medieval dress that have a similar effect of universalizing the parables, but none have the power of the animal images.

A totally different use is made of images in one of the nine Haggadahs in the exhibition. The seminal Amsterdam Haggadah of 1695, the first illustrated with copper-plate impressions would become the visual template of the Haggadah for at least 150 years. Many of the images, created by the proselyte Abraham ben Jacob, were derived from engravings of Matthaeus Merian in 1630. These images seem to place themselves in a contemporary and “real” world. There is the depiction of naturalistic space, recognizable buildings and palaces, even as the actors and actresses play out their roles of oppression and liberation. These images are not fabulous but simply down-to-earth as they constantly allude to contemporary reality of the 17th century. They challenge the text to be contemporary, just as the Haggadah tells us, “each individual must see himself as if he went out from Egypt.”

The proof is, of course, in the details. Each plate has one or two verses at the bottom identifying the subject. In the midst of the text that tells of how the Jews cried out to God and He “saw our affliction” and “our burden” the copperplate engraving depicts the building of the store cities Pisom and Raamses along with Moses slaying the Egyptian as he “looked this way and that” and “struck the Egyptian.” Unlike the Fables the pictures do not illustrate the text at all. In fact they have no direct textual base in the Haggadah. Rather they set the biblical scene, establishing through a pictorial narrative that combines two distinct verses a paradigm of oppression and violent reaction. While the general theme in both text and image is oppression, the image encourages violent resistance, quite different from the thrust of Haggadah’s narrative.

The clarity of the etchings in this first edition allow for crucial details to be seen, such as in the image of the Murder of the Firstborn “and Pharaoh commanded…every son born you shall throw [into the river]” This is combined with the finding of Moses by Pharaoh’s daughter. Again it is ambiguously placed in a text that deals with God’s strength of salvation “With a mighty hand…” that describes plagues that rained down on the Egyptians. In contrast the image concentrates on the grief and sorrow of the parents seen on the far shore as a horrifying procession of drowned babies float down the river. In the distance a contemporary Renaissance city is seen nestled in the hills as figures casually cross an arched bridge. The placement of this image in this context contextualizes God’s salvation, reminding us of the terrible suffering that proceeded it. That oppression is firmly placed in the contemporary world. Utilizing biblical texts the artist comments and in fact criticizes the Haggadah for its omission. Interestingly the original image from the non-Jew Merian omits the dead children and the wailing mothers, simply depicting the finding of Moses. The Jewish image is inherently more powerful as it conflates two related narratives and effectively links the salvation of Moses by Pharaoh’s daughter with God’s salvation of the Jewish people.

Not all picture books can ascend to these heights of textual commentary. Some remain simply decorative, giving visual joy to the reader. Others are content to illustrate a text, providing visual markers, mnemonics that root themselves in the reader’s imagination. As we have seen, other books with pictures can elaborate or comment on the text, joining it as a full partner in the creation of meaning and content. Whatever kind of picture book we encounter it is surely wise to pause and ponder that frequently the addition of images to text is considerably more than just making a pretty picture.

Supreme Hebrew Printed Books

Kestenbaum & Company

12 West 27th Street, New York, N.Y.