Robert Feinland’s Paintings

One thing is certain about Robert Feinland. He has shuls on his mind. His career has spanned over 40 years, exploring landscape, cityscape, sculpture and abstraction. For many of those years he has focused on the relentlessly changing urban landscape of New York, feeling the necessity to document and, in some way preserve, the physical fabric of the city he loves. A selection of recent paintings, most concentrating on the Crown Heights community, is currently at the Chassidic Art Institute. Many of the images are of shuls.

Brooklyn born, he was in a way typical of the 1960s hippie generation until a chance encounter on the subway with a Chabad Chassid changed his life. Seeing the way Feinland was dressed, the chassid simply said, “Hey man, you have to go talk to Rabbi Schneerson.” The man wouldn’t leave him alone until Feinland agreed. He went to Crown Heights and was very impressed with the totally unique world of Jewish religiosity. For a while he attended HaDar HaTorah, the newly founded Chabad yeshiva for baalei teshuva. While he never did speak to the Rebbe, he was for quite awhile immersed in Jewish religious life. As the artist comments; “I did come in touch with my soul through my experience with 770 in the 1960s.” Life has never been the same for him.

During the 1980s Feinland began painting the Lower East Side, concentrating especially on the downtown synagogues. His technique, plein air painting (working outdoors in front of the scene first favored by the early Impressionists), demands that he return over and over to the motif until he is satisfied with the painting. Perhaps out the rigors of this discipline and the repeated confrontation with the physical presence of the scene, he has developed a unique approach to depicting urban landscapes. The curvilinear perspective he uses is at first unsettling, reminding the viewer of wide-angle (fisheye lens) photography. But of course his dedication to on-site observation is anything but unthinkingly photographic. Rather he is determined to fuse the optical effects of seeing a street scene up close with the attendant awareness of its inherent social importance. Incidentally, this technique was first discussed by Leonardo di Vinci, ca. 1500, and its multiple perspective points is paradoxically considered as an approximation of how the human eye actually sees.

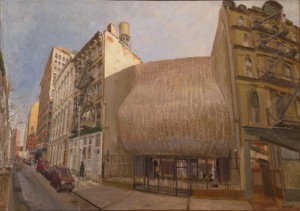

Synagogue For The Arts (2000) demonstrates the use of curvilinear perspective to visually situate a Jewish house of worship on an otherwise drab Soho street. When a visitor stands in front of the shul, one just sees it as an odd bulging structure sandwiched between 19th century cast iron facades. But of course in order to see the synagogue in context of its neighbors one must scan the block horizontally and then up and down to get a sense of its physical presence. And that scanning of multiple points of view is exactly what Feinland is representing in his painting. By curving the street and its buildings he provides the experience of profoundly encountering this shul. The visual experience of the painting creates an approximation of confronting the incredibly anomalous and dramatic sculptural nature of the shul’s architecture. This is made even more dramatic since the painting depicts the shul in the late afternoon when it is in shadow, thereby emphasizing the mass of its form without the obviousness of morning sunlight.

Aside from this formal analysis, Feinland may be ironically commenting on how the shul actually came to be there on White Street in Manhattan. Originally there was a synagogue for the civic center workers on Duane Street that was razed to make way for the Jacob Javits Federal Office Building. This shul was “imposed” upon the adjacent commercial properties as part of the eminent domain settlement. Thus the “distorted perspective” of urban planning and resulting need to address its consequences.

Feinland’s painting of the Millinery Center Synagogue (2005) is part of a similar social commentary. Here the narrative is one of valiant resistance. The forces of development, exemplified by the blurred rushing traffic in the foreground, confronted the brave little congregation of the Millinery Shul and, as is dramatically expressed in Feinland’s painting, it has become “the little shul that could” to resist the relentless real estate development of the late 1990s. The leadership refused to sell its property in the face of a plan for massive redevelopment for the entire block. It remains a synagogue there today. While it struggles, it continues to function providing multiple much needed Mincha and Mincha/Maariv services.

The image centers on two little buildings on Sixth Avenue just north of 38th Street, the Millinery Center Synagogue and its four-story neighbor to the right, surrounded by empty lots ready for development. A sidewalk bridge already threatens to the south and the empty northern lot’s diagonal crane reaches skyward pointing the way to the inevitable future. Pictorially, all of the towering forces in this urban environment are arrayed against this diminutive bastion of faith.

Feinland returned to the roots of his faith in the last decade as he concentrated on urban paintings of the Crown Heights neighborhood. The Mikveh at Union Street and the venerable Chovevei Torah synagogue naturally figured in his gaze. Not surprisingly 770 Eastern Parkway became a major motif for Feinland to explore. After being away for so many years, his repeated visitations over the last 14 years have earned him the reputation as a well-known neighborhood artist.

Almost half of Feinland’s paintings in this exhibition contain the iconic 770, depicted from different angles and at different seasons. The largest is a diptych, Conversations Under the Moon and was completed this last year after at least 20 outdoor sessions. It was well worth all the effort.

Feinland has again bent the space in the painting, applying an arching curvilinear perspective, to provide us with a palpable sense of almost two city blocks; from 770 itself, to the Yeshiva and World Headquarters and past the modernistic Jewish Children’s Museum to the row houses that stretch to the corner of Albany Avenue. He has also broadened our view to include the Eastern Parkway Pedestrian Mall lined with park benches. The sidewalk is populated with dozens of young men, many talking on cell phones, and a handful of women with strollers, all enjoying what appears to be a sunny Spring morning. One is struck by the visual tension between the left panel whose perspective seems to “normally” recede in the distance, and the street in front of 770 that sharply curves to accommodate a more frontal view of the architectural symbol of the Lubavitch movement. It is deeply significant that Feinland’s diptych manages to simultaneously resolve the perspectival conflict and yet maintain its tension. Central to the concept of curvilinear space is the notion of simultaneously different visual points of view. Here the two-part image combines the iconic 770; the Rebbe’s seat of power and holiness; and the street stretching away into the more mundane world of the surrounding community.

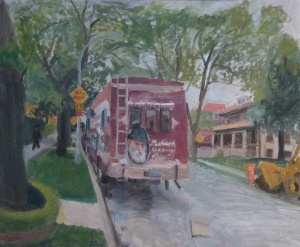

As is not surprising in Crown Heights, the Rebbe is never far from anyone’s consciousness. Mitzvah Tank is a quiet visual essay on the ubiquitous image of Rabbi Schneerson. A parked Mitzvah Tank (which is essentially a traveling shul), seen from the back, dominates the simple view of a tree-lined Crown Heights street. Situated in what is almost exactly the center of the painting is the Rebbe’s familiar image next to: “Moshiach is Coming Now!” In the simplest of ways Feinland expresses a fundamental belief of an entire community.

About three blocks from 770 is the Rebbe’s personal house, now sitting unused. Feinland’s intense curvilinear image seems to echo a considerable amount of the controversy and tension over the great leader’s legacy. In the sweep of the three houses shown, his house is cast into dramatic relief, seeming to tower over the viewer just as the jagged tree on the foreground curb stabs the sky above. It is a painting of sharp angles and twisted forms that are held in place by the green grass lawn and stately pine tree immediately in front of the house itself. Like many of his best paintings, it manages to combine complexity, drama and commentary in a beautiful image.

As we all know the command to “draw close to Hashem” is a fundamental religious act. Once that was originally satisfied by offering sacrifices at the Temple and now, without a Temple, we minimally fulfill it by learning Torah and daily prayer. Robert Feinland’s synagogue paintings bend space with a curvilinear consciousness, bringing close houses of Jewish faith and belief, allowing the viewer to be brought close both visually and mentally. In his way his work becomes another avenue through which we can “draw close to Hashem.”

Chassidic Art Institute

375 Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, New York