View from the Shoah

A well-known Midrash tells of the destruction of Jerusalem and how the Divine Presence removed itself from the holy precincts of the Temple. Stage by stage the Divine Presence retreated from the holy land of Israel as the Land was defiled and the Jews were exiled. We are told, as a kind of consolation, that the Divine Presence has gone into exile with us and metaphorically awaits redemption.

The Midrash transforms this event because it cannot countenance the reality of Jews exiled alone without a palpable connection to their God. It is too much to bear. Natan Nuchi’s art similarly re-imagines the consequences of an event that no one can countenance.

Natan Nuchi, an Israeli artist living in New York, has been painting single figures that evoke Holocaust victims for the past twenty years. As a son of a survivor his youth in Israel was characterized by the absence of grandparents and his parents’ oppressive silence about the immediate past in Europe. The shame of Jewish victimhood was unconscionable for most Israelis. The majority of his creative life has been spent in trying to extricate himself from the murder of six million Jews. Paradoxically, he has been continually drawn back to the victims by painting them one by one.

In 1984 he created The Binding of Isaac, an enormous spray enamel painting on canvas depicting Isaac cradled, pieta-like, in his father’s arms. Abraham looks passively into his son’s terrified eyes seeming to say, “Who is this victim?” Much of Nuchi’s subsequent art asks a similar question by seeing the “textual” reality of the millions murdered in the visage of one metaphorical individual.

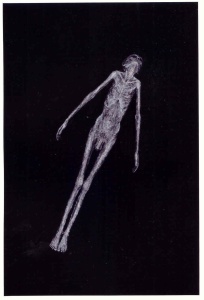

Untitled (1994) is emblematic of the works of that decade. Like souls unable to find rest, single figures float vertically, horizontally or diagonally in a black void. Males and females are shorn of all personality with their arms limp at their sides and feet stretched out, passive victims so starved that one can see through their flesh.

There are no identifying marks or symbols to link them to the Holocaust, only the emaciated specter of suffering proclaims our era. For Nuchi their anguish is universalized as an accusation against all because the evil that the Shoah unleashed continues to live in the soul of man. Sensibly, his paintings from in this series are mostly untitled. Once perpetuated it is forever possible to be repeated and for Nuchi, that has changed everything. He has brought the millions unburied back to haunt our consciousness because, after all, the victims and their suffering define the Holocaust. He refuses to mitigate the tragedy with reassuring visions of survivors or vignettes illustrating morality triumphing over evil. His unflinching paintings tell the story that evil won and the majority of Europe’s Jews were murdered. He cannot avert his eyes.

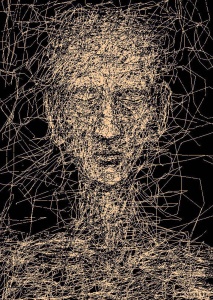

In 2000 Nuchi presented a haunting collection of 15 digital drawings. These Iris prints were computer generated using a computer mouse to draw the image. A haze of computer graphic static coalesces into heads and figures that assault us with their vulnerability and suffering. The background here is no longer an existential void but is agitated and bristling with nervous strokes and slashes as if the silence of shame will no longer be tolerated. These prints begin to strike out at the surrounding world, demanding acknowledgement of a social context and, by implication, a social responsibility. The computer technology, evidenced in the ever-present pixels deliberately left visible, emphasizes psychological distance and “cools” the images of emaciated heads and screaming mouths so we can bear to look at them.

One, Face, 7 (1998), peers across time and memory as if glimpsed from another universe. White splotches threaten to disintegrate the image, a reminder that our memory of the event may be in danger of expiring. Guarding against this, Nuchi will not allow us to forget the victims.

Face With Eyes Closed (1999) covers an entire wall (80” x 60”) and is a commemoration to the victims of all the scratches, offenses and indignations that Jews were forced to bear before they were murdered. Their suffering becomes their identity even as Nuchi attempts to resurrect them. Without reducing the enormity of the tragedy he forces us to confront individual lives that were reduced to abject horror. For Nuchi, the irreducible text of history must be transformed by the metaphor of art. There can be no other way, the reality is too terrible to gaze at, and therefore the medium of art and computer technology must intercede to allow us to acknowledge the victims of Europe’s evil. In image after image Nuchi places a layer of aesthetic process between the gristly horror and us so that we may not so easily forget, so that we will remember the victims. His use of artistic metaphor exactly parallels the Midrash in its attempts to penetrate an unbearable historical reality.

Last year Nuchi created another series of Iris prints that radically altered his view of the victims of the Holocaust. Suddenly color; violently optimistic colors of yellow, light blue, green and ochres invaded the images to challenge the gray, black and white universe of death that previously reigned. These exciting prints fundamentally challenge the formal means of the earlier images. The images are a frontal assault on our consumeristic society that banishes anything grim or disturbing. By combining his unrelenting repetition of single abandoned figures and anguished heads with unabashedly joyous color Nuchi creates an almost unbearable tension between the security of the lives we live here in America and the horror that is only fifty years old. He seduces us with the sensuality of color as we are trapped in the consequences of the last century.

In one of the latest prints, Figure 4, a lone individual stands confronting a haystack of blazing yellow harvest. The figure is black, dense and unrelieved against the blinding beauty of nature. It is as if one of his lost, untethered figures had found their way into an unimaginable future. Mysteriously the image becomes more complicated as we notice two enormous fingers intruding right and left.

Fingers and digits have reappeared in Nuchi’s paintings and works lately. He has been obsessed for years with small drawings of fingers, digits as metaphorical human forms. In notebook after notebook his drawings proliferated. Some pages would have three or four, some fifty or sixty digital human forms made up of a finger, nail and cuticle. Now these radical fingers have emerged in the main body of his work.

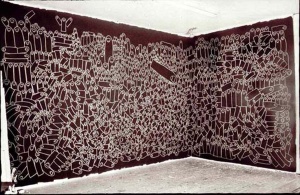

In January 2003 Nuchi did a chalk drawing on the two largest walls of his studio. One wall is 11′ x 18′ and the other measures 11′ x 9′. Each wall had been painted flat black. The massive drawing contains hundreds of fingers that make up a figurative social universe. It is tentative and impermanent. At first a mystery, it slowly reveals itself. It is a kind of aesthetic response to the Holocaust.

The wall drawing, Untitled (2003) is a massive assembly of digits composed of interconnected groupings. They have been gathered here for some unfathomable purpose. Some of the digits appear larger than the others and one even seems to be held aloft and carried in a procession. In the context of the rest of Nuchi’s work this massive image is singular for its multiplicity of figures and their connections. They represent a society that is tragically denied to the earlier single victims. These works, including dozens of recent paintings and drawings, are a startling response to Nuchi’s unremittingly isolated Holocaust victims.

The victims of the Holocaust cast a long shadow from the twentieth century into the present. They are inescapable. They are not forgotten in Natan Nuchi’s work. In his latest work he may have finally found a response to the victims that will free his soul from their merciless grip.

Natan Nuchi may be contacted at [email protected]

Lecture: Friedman Society at Jewish Museum; October 27, 2004