Meer Akselrod: Painting his People

Empathy and memory meet in the work of Meer Akselrod (1902-1970), the Jewish Russian artist who defied aesthetic convention and totalitarian dictates to relentlessly pursue his personal artistic vision of painting the Jewish people. His quiet courage in the face of epochal changes that convulsed his Russian homeland cannot be overestimated. They are amply attested to by his artwork, not the least of which are two pen and ink drawings, Pogrom, from 1927-1928, currently at the Chassidic Art Institute.

Pogrom #41 depicts a woman about to be arrested on the steps of her house. Her child clings to her baggy dress as she raises her hand in submission and fright. The hood of her scarf obscures half her face, exposing only her fear and desperation. Akselrod’s expressive use of a black ink wash on the left side echoes the anticipated grasp of her attacker. We can easily see this encounter is not going to come out well.

It is important to historically place this work. Akselrod was then living in Moscow and taught and exhibited at the VKHUTEMAS, the Soviet art and design school (similar to the Bauhaus) set up by Lenin in 1920. These drawings most probably reflect his experiences and/or reports of pogroms in Belarus in the aftermath of the Russian Civil War (1917-1923). Whether this drawing is from his own experiences or just reflections of these terrible events, he has fully involved us in the fate of this woman and child. Our empathy is deeply evoked.

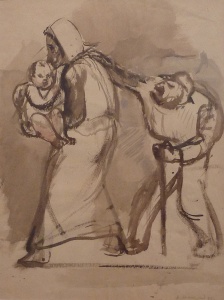

A rather different experience is seen in Pogrom #40. Here we witness an attack unfolding in a bizarre scenario. Akselrod’s Rembrandt-like rapid strokes depict a short brutal man grasping a fleeing woman’s shoulder. She is carrying an oddly contented baby while this little man, his fist holding a cane, is about to attack her. Even though he is so much shorter that she is, still he is terribly dangerous, clearly driven by his demented hate. As we are drawn into this unfolding scene we understand that it is the centuries old irrational hate that fuels the pogroms that decimated our people then and continues to attack us even today. Akselrod’s unflinching depiction arouses a historical memory shared by all Jews.

Driven by a fearful Russian government from their provincial Belarusian hometown of Molodechno during the First World War, Akselrod’s family wandered Russia and finally settled in Minsk in 1917. As a developing artist he gravitated to Moscow and quickly became part of its thriving post-revolutionary artistic environment. He was quickly lauded as a major talent and yet insisted on charting his own aesthetic course. He did not seem to be influenced by the uniquely Russian modernism flourishing at the time, expressed by fellow landsman Marc Chagall or the emerging abstractions of Kandinsky and El Lissitzky. Those artists and others (many of them Jews) would blossom into the highly influential Russian Constructivism, itself espoused in the VKHUTEMAS Institute that Akselrod taught in. And yet he stood apart. Independent.

Akselrod’s obsession was with his people. He would sojourn out into the countless Jewish settlements in the countryside, searching for his subjects. Mark (Meer) Moiseevich demanded; “No, We must live in a house, among the locals. To see the way of life. Get to know people. We must try and earn their trust and… persuade them to pose for us…” When he was told there were plenty of Jews to paint in Moscow he replied: “No, they’re not right. The types you’re talking about have become too familiar. There is no freshness of perception. It’s all evaporating, slipping away, while there the Sholom Aleichem atmosphere has been retained…” He saw his job as preserving a vanishing Jewish culture. And over and over he produced “a study of the prominent characteristic of types of Jewish poverty… [significantly] an insight into the very essence of national character.” The work of the 1920s and 1930s was touched by the expressionism of the times filtered through the influence of the School of Paris, distantly seen from mother Russia. And yet he insisted on his Jewish brethren as his subjects because that world must be preserved. Akselrod’s artwork would not succumb to the newest dictates of official aesthetics, the Social Realism to celebrate the Party and the cut-out Heroes of the Revolution.

A brilliant example is a simple portrait in profile of a young man done in 1928. Almost classical in proportion and its central placement on the page, this drawing in nonetheless quite modern in its selective approach, only giving us the essential information to define clothing, pose and character. However it is the deep introspection of the lad depicted that sets this drawing quite apart, inviting us into his interior universe of hope, expectation and anxiety. Placing this young Jew in the dangerous turmoil of Soviet Russia moves this artwork into the realm of historical commentary.

Akselrod’s skills as a portraitist were evident early in his career and helped sustain him as a working artist. Interestingly they extended to inanimate objects as well, as we can see from his frontal depiction of The Red House in Minsk (1928). Again there is a classical balance of the composition that allows us to move around the spaces of the painting without getting lost, as it were. The three-windowed dormer crowning the roof is echoed by the woman seated on the bench in the foreground, firmly holding the center of the image, top and bottom. We are intrigued by the contrast between the solid brick house and its incongruous aspects of ruin and disrepair on each side. Since we don’t know its use or function, the Red House remains a delightful mystery.

From the mid-1930’s Akselrod was involved with the famous Moscow State Jewish Theater and its regional affiliates as a set and costume designer. This was one of the few places in Stalin’s Soviet Union that a Jew could express themselves in Yiddish and admit some form of Yiddishkeit. For an artist like Akselrod it was an aesthetic oasis in a sea of Socialist Realism. He worked on many different projects, including Sholem Aleichem’s “The Enchanted Tailor.”

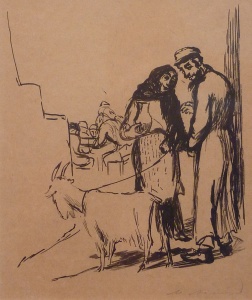

It was with this material that Akselrod flourished even under the harshest conditions. In 1941 he was exiled to predominantly Muslim Alma Ata, Kazakhstan, a location over 2500 miles from Moscow, near the Chinese border. A common wartime tactic of Stalin was to move vulnerable industries far from the German front and to punish troublesome artists and intellectuals with internal exile. Nonetheless the drawing from the “Enchanted Tailor” series done in this time is a masterpiece of succinct illustration. His crisp economy of line and confidence in every detail lends a liveliness and spirit to the image that evokes the narrative even if you are not familiar with the text. A portly Hasid is pontificating on his porch while a poor stranger schlepping along with his trustworthy goat listens, seemingly unable to pass quietly by. Indeed the story concerns a poor tailor who is sent by his wife to buy a goat to help feed his family and has innumerable mysterious adventures in attempting to return home. Akselrod captures the heart of the story perfectly.

Towards the end of his life Akselrod turned his attention to a subject that directly related to his earlier concern with pogroms: the Holocaust. Here the sufferings of his people were couched in images that were slowly emerging in the artistic consciousness of the time, mainly the use of the crematorium chimney. It is in Smoke (1969) that the artist seeks to combine the horror of the slaughter and cremation of millions of Jews and the survival of a “saving remnant.” The Jews depicted in the foreground in concentration camp stripped uniforms seem to walk away from the fearsome furnace behind them. They propose a kind of collective memory and empathy for those of us who did not live through those events, but knew them from afar.

Meer Axelrod worked constantly hard and purposely earning his living as a Jewish artist in some of the most difficult and challenging times imaginable in Soviet Russia. He maintained his vision to preserve a record of the Jewish people in Russia both as he experienced it and as it had been in the societal breakdown of one hundred years earlier. His piety was to his people; their joys, sufferings and struggles. It is a memory we do well to honor.

I am deeply indebted to the monograph Meer Akselrod by Elena Akselrod (Mesilot, Jerusalem, 1993) and the Chassidic Art Institute for information, background and images of Meer Akselrod’s work.