Jacqueline Nicholls: New Works

Jacqueline Nicholls, a Jewish artist from England, presents us with a formidable challenge. Namely; what is the role of a contemporary Jewish Woman artist and how does one confront patriarchal dominance? She presents her response to both queries in her current exhibition at the JCC Manhattan beautifully curated by Tobi Kahn and organized by Tisch Gallery director Megan Whitman. The results are breathtakingly forceful, subtle and insightful.

For Nicholls a Jewish woman must be armed with a deep and abiding knowledge of Torah, Tanach and Talmud, hand in hand, if she so chooses, with an artistic immersion in what has been called the Feminine Crafts, i.e. the fabric arts and traditional “Women’s Work.” This Jewish artist affirms that she must be especially articulate in Jewish texts to practice a “counter-voice to turn the narrative” and indeed that is what she does both in her choice of subject and exposition thereof. Her explorations are exhilarating.

The exhibition has three components: “Gather the Broken;” meditations on the Omer; “The Kittel Collection;” studies of a ritual garment and; “Ghosts & Shadows;” considerations of women in Talmud.

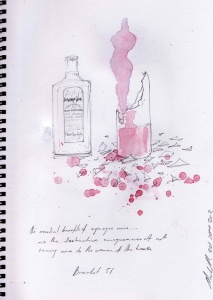

The series of 49 Omer meditations explore the multiple aspects of loss that the days between Passover and Shavuos engender. As an aspect of the semi-mourning that the Omer demands so too Nicholls looked to the minutia of her daily existence for inspiration. Her emphasis on that which is broken reflects, “only by acknowledging the broken, imperfect aspects of daily life [can]… creativity and a new life can be revealed.” This new and renewed life is of course accomplished on Shavous in the acceptance of the Torah at Sinai.

This year she created this series of small drawings, one created each day of the Omer and posted on her blog, accompanied by a daily poetic commentary of Amichai Lau-Lavie. The strength of these drawings, aside from the pure skill of her draftsmanship, is that Nicholls manages to totally personalize the obsessive ritual of Omer counting in a way that internalizes both the ritual and the meaning of each individual day even while making a unified work of art. This asserts a uniquely Jewish notion that from brokenness creativity arises.

The kittel is a ritual garment that cloaks us in white in the effort to convince ourselves that we can actually be “white,” as Isaiah (1:18) proclaims that; “Come, now let us reason together, says Hashem. If your sins are like scarlet they will become white as snow.” So too the other times when we use the kittel to bury, to marry, to pray on Yom Kippur or lead the congregation on momentous occasions. We don the costume of purity in the effort to become pure. In a similar manner Nicholls has created a series of 10 garments based on the kittel template to explore how a garment can be used to transform meaning and identity in the Jewish tradition.

The Shame Kittel is little more than a simple apron, stained black at the bottom edge and discolored a sickly yellow up around the neck. Buried in the yellow is an array of epithets used against the Jews by anti-Semites of all ages. What Nicholls is affirming is that an important part of Jewish identity is never forgetting what those who hate us say about us. Nonetheless a number of the other kittels are more positive, especially the Majestic Kittel and the New Kittel. The latter offers its seams stitched in gold and an embroidered label in gold with the Shecheyanu prayer, emphasizing our thankfulness to God for giving us new and beautiful things to wear.

Perhaps the most moving kittel is the Mourning Kittel as it transforms the shirt of mourning into a lurid expression of mourners’ emotions. Not surprisingly one of the sleeves is shredded from a frenzy of kriah, the mourners’ ritual tearing of garments. The collar is high and closed tight by a dense coil of metal wire around the neck, deeply expressive of the choking pain of loss. Finally in the center of the ragged garment, somewhere between the chest and stomach, the seams come together to form a hollow that sinks into the interior of the garment. It is as if this is where the pain of bereavement has burrowed into the very substance of the mourner. The symbolic power of this garment is awesome.

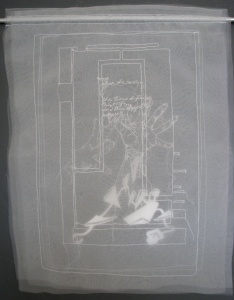

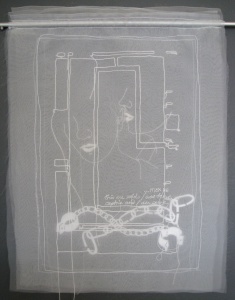

In both the Omer series and the Kittel Collection Nicholls utilizes the vocabulary of Jewish ritual to talk about larger issues. In “Ghosts and Shadows: The Women Who Haunt the Talmud” she hones in on ten female characters who “turn” the overwhelmingly male narrative voice of the Gemara into a discourse that recognizes female agency and power. She does this utilizing a completely unique medium consisting of multiple layers of translucent material (silk organza), each 15” x 20”, that beguilingly combine white sewn text, image, embroidery and the actual outline of the Vilna Talmud page being used, each sewn as a distinct layer.

On Taanis 23b, the Gemara relates a story about Abba Hilkiah, a grandson of the famous Honi the Circle Drawer. This sage was constantly beseeched by the Rabbis to pray for rain, as he did when necessary and was always successful. Once he was sent for but instead led the messengers on what seemed like an illogical wild-goose chase. At the end of this journey he came to his home whereupon his wife greeted him bedecked in her precious jewelry. He had her enter the house first and then he bid her to join him on the roof to pray for rain. She stood in one corner, he in the other and the rain began to fall on her side. When asked to explain his wife’s strange appearance upon greeting him, he assumed it was to keep him from looking at other women, thinking her as but an object of desire. Thereupon her success at beseeching God for rain opened his eyes to her real virtue. He then explained that she was clearly more meritorious than he since she stayed at home and gave bread to the poor which they could enjoy immediately while all he did was to give the poor money which they had to wait to enjoy. Nicholls quotes the narrative on the top layer and through the outline of this Talmud page we can glimpse the wife with rings on all her fingers and copious necklaces even as two challah loaves hover like clouds over falling shafts of wheat. In this narrative that easily could have been missed amongst many other elements of the story, a woman’s worth is closely linked with elemental acts of kindness and resulting access to the Ruler of the Universe.

In Rebbe’s Maid: The One Who Stood Between Heaven and Earth the heroine likewise operates counter to prevailing Rabbinic wisdom. Kesubos 104a relates the last days of Rebbe. The Rabbis decreed a public fast and forbade anyone from saying that Rebbe had died. His maidservant, a wise and pious woman, ascended to the roof and beseeched Heaven to allow him to live. But when she saw how terrible was his suffering, even struggling to take off and put on his tefillin, she changed her prayer and asked Heaven to take him. But since the Rabbis did not cease their prayers, she took an earthenware vessel and smashed it from the roof to the ground. The sound startled the rabbis, interrupting their prayers, which allowed Rebbe to die. She acted in wisdom, kindness and mercy and therefore we learn from her that when “one suffers greatly from an illness, and there is no chance that he will live, we are required to pray for his death” (Artscroll Kesubos 104a, note 7). Nicholls has depicted the old woman’s outstretched hands as she has just thrust the pot off the roof. On another layer we see the broken shards among Rebbe’s tefillin. Again it is a woman who understands what the men do not and effectively turns the narrative.

While each one of the narratives that Nicholls chooses explores another aspect of hidden women in the Talmud, Shmuel’s Daughters: The Ones Who Knew What to Say to the Rabbis perhaps best illuminates Nicholls’ own methodology. Ketubos 23a continues an exploration of the principle of ha’peh she’assar, literally “The very mouth that has forbidden is the mouth that has permitted,” wherein a prohibited state is established solely through the word of a particular person, that person has the right to report that the prohibition does not apply in their case. Here, tragically, Shmuel’s daughters were abducted and then returned, paradoxically by their captors. The daughters one by one entered the study hall and separately testified, “I was captured but I am pure.” They were believed and allowed to marry a cohen. When their captors later entered the study hall, R. Chanina exclaimed, “These women are the children of a halachic master;” indeed they were the children of Shmuel. The Gemara has no idea what actually happened to the women in their captivity. All it admits is that through their knowledge of the principle of ha’peh she’assar the women skillfully cleared the path to their desired of marriage of a cohen. Nicholls’ image is deceptively simple; the foreground shows the broken chains of their captivity or more likely the chains of their suspected defilement in contrast to a simple stitched line of one daughter whispering in the ear of the other the key to their halachic freedom. For these women of the Gemara, it is Torah knowledge that liberates them much in the same way Nicholls spins her artistic magic through sophisticated Talmudic thinking.

Jacqueline Nicholls is an intriguing artist. Brought up as a well-educated Modern Orthodox woman, the vast repository of Jewish text and sensibility are second nature to her. She has now tackled the Daf Yomi with her very own Draw Yomi blog, creating a drawing for each daily daf she studies. Equally familiar to her is the language of postmodern art making with seasonings of text, image, and diverse materials, especially those found in the ‘women’s arts.’ She sees the Talmud as being naturally feminine, deeply aligned with Women’s Work since it is fundamentally non-linear, constantly switching between the minutia and the global, much in the same way as weaving or embroidery must keep in mind the big-picture while it concentrates on each and every stitch.

She is an inspiration of what a thoroughly informed modern Jewish art can be. It seems like a truly new dawn is breaking.

JCC Manhattan

334 Amsterdam Avenue at 76th Street: Laurie M. Tisch Gallery

www.jccmanhattan.org

Jacquelinenicholls.com