Chagall Redux

Chagall’s reputation needs no burnishing and yet refinements are always welcome. Indeed the Nassau County Museum of Art has mounted a wonderfully extensive survey of Chagall’s works with a unique emphasis on his 1957 Bible series of hand-colored etchings that significantly casts many aspects of his work as uniquely Jewish. Amid the complexity of Chagall’s entire oeuvre, this is deeply significant in the exhibition history of non-Jewish institutions.

The current show at the Nassau County Museum of Art is sensitively curated by former director and guest curator Constance Schwartz. The first floor features an exciting survey of many of his early works from both private and public collections (including A Pinch of Snuff from 1922—a rabbinic figure about to take a olfactory hit) all of which emphasize the wide range of Chagall’s imagination and pure joy of image making. Further along we see examples from his etchings of Gogol’s Dead Souls, his problematic images of “universalist” crucifixions, clowns, circuses, and many playful pastiches of his signature motifs; flowers, lovers, flying animals and other fantasia all held together with vividly beautiful color. It is tour-de-force of Chagall the master conjurer of instant visual delights.

From a biographical perspective Chagall’s last painting, Job finished on March 28, 1985, the day he died, is perhaps the most moving. At the age of 97 Chagall, who had continued to create artwork seemingly unabated, was “deeply aware of his own mortality,” and therefore this work and its subject takes on added significance. The gouache on paper was actually a preparatory image for a massive tapestry that was in fabrication at the time for the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, where it has been since 1986. This commissioned work, created in close collaboration with the renowned weaver Yvette Cauquil-Prince, depicts Job and his wife and was dedicated to the disabled of the world, a more than fitting appropriation of the tragic story of Job. Poignantly it is a reflection of Chagall’s own tortured struggle with faith, Jewish identity and the vicissitudes of 20th century history.

Upstairs on the second floor 50 of 100 hand-colored images from Chagall’s 1957 opus Bible are displayed in quiet splendor. Next to each 24” x 18” image is the biblical text. In a superficial way we are well accustomed to these images. As we have recounted many times in these pages, Chagall first began his Bible etchings from 1931 to 1939. Interrupted by the war and exile he returned to France in 1952 and finally completed the black and white etchings in 1956 when they were published, along with a separate limited edition of etchings that were hand-colored by Chagall himself. This selection at the Nassau County Museum of Art is on loan from the Haggerty Art Museum of Marquette University in Milwaukee.

It is crucial to note a fundamental difference between the black and white edition and the hand-colored images currently on display. Aside from minor printing variations between sets, all of the black and white images are identical. The opposite is the case with the hand-colored etchings, each is totally unique since each was thoughtfully and sparingly colored one by one. And most importantly, each was the artist’s refinement and comment on work he had done up to 24 years earlier.

Almost 60% of the etchings were originally done before Chagall’s exile, the War, the Holocaust, and the devastating death of his beloved first wife Bella.

The Chagall hand-coloring his interpretations of the biblical narrative was a deeply different man from the man who first created them.

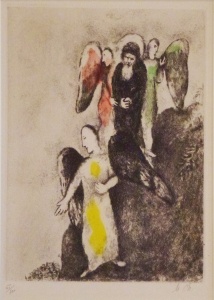

Descent Towards Sodom isolates the patriarch Abraham as each angel, one red, one green and one yellow, contrasts with the somber blacks of our forefather’s cloak. The mood is filled with a mournful tension as Abraham realizes the terrible and total destruction about to occur.

Interestingly the theme of violence is further developed in Moses Spreads Darkness over Egypt. Here Moses is depicted as slightly cross-eyed demonic prophet, his staff raised heavenward, while the angel, here accented is a flash of pinkish red, is positively aggressive.

Violence is again evoked in Crossing the Sea as we observe the Children of Israel led by a yellow clad angel while Moses in pure black and white orchestrates the miracle in the lower left. While the sky blue of much of the sea seems to conflate sea and sky, the red of the drowning Egyptian army fully seals their watery fate.

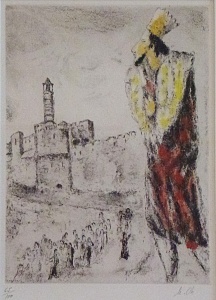

In many of the Bible images Chagall abandons direct narrative and instead focuses on certain psychological “portraits” of biblical characters. King David is transformed here by his yellow crown, face and mantle that elegantly contrasts with his earth red and black gown. He now towers over his people arrayed before the anachronistically depicted Tower of David.

Chagall’s powers of empathy are of course central to his ability to depict such a vast range of biblical personalities.

Elijah Touched by an Angel is perhaps the most heartbreaking image in the suite. The prophet in Kings I 19:5 has fled the murderous Queen Jezebel to the wilderness of Beer-sheba and despaired of his life, proclaiming, “It is enough! Now, Hashem, take my soul…” When in absolute weariness Elijah falls asleep, an angel comes and gently touches his head, commanding him ‘to get up and eat for you have far to go and much to do yet.’ Chagall’s Elijah is a Chassidic rebbe from deep within the artist’s own past and a prophecy of his own future. Even at the age of 70 Chagall had almost thirty more years of making some of the richest Biblical art the 20th century had ever seen. His legacy is shown to great advantage in this stunning exhibition.

Nassau County Museum of Art

One Museum Drive, Roslyn Harbor, New York

Nassaumuseum.org