The Abstract Omer paintings of Yitzhok Moully

I have always had a problem with the Omer. Doing the mitzvah of counting the omer was of course pretty easy. Remembering to start the second evening of Passover and remembering to stop the day before Shavous took a little concentration but somehow I always managed. No, for me the nagging problem was always why was I doing this in the first place, other than the fact it was a biblical (according to the Rambam) commandment. Of course I understood that in some way our counting echoes the bringing and waving of the first barley crop in the Temple the second day of Passover. But we didn’t do that 49 times. Admittedly there is the Midrash Rabba and Midrash Tanhuma that relates that the Jews were told in Egypt that they would receive the Torah 50 days after the Exodus, and therefore passionately counted down the days to Matan Torah. But why did God make that a commandment once we already had the Torah? And I surely didn’t need to count 49 days to figure when Shavous arrived: God already commanded us to keep a calendar.

It would seem that the rabbis shared my puzzlement and so in the Zohar the kabbalists started to link our counting with 49 permutations of the sefirah, lending a mystical and esoteric aspect to the mundane act of counting. Conveniently, the seven lower sefirot can be associated with the seven weeks between Passover and Shavous, and each day of the week also is associated with a specific sefirah. Combine the two and you have a complex esoteric system. One reason given for this system was the need to relive the ascent through 49 “gates” of impurity of the Egyptian bondage to the purity of revelation at Sinai. Now this system certainly added meaning to a simple count but, not being a kabbalist, its personal application is elusive.

Nowadays we think of ourselves as distant from the merit of receiving the Torah, so the notion of day-by-day self-improvement between Passover and Shavous has become paramount. A number of ethical tracts have responded to this (Amazon lists at least 10 from every conceivable point of view) including Chabad’s Rabbi Simon Jacobson’s The Spiritual Guide to Counting the Omer. Not surprisingly contemporary Jewish artists have begun exploring this subject, including Jacqueline Nicholls (reviewed here September 2012). For the last three years she has been doing a drawing a day for each day of that year’s omer cycle. In 2011 she was inspired by an exhibition seen at MOMA and performed “a daily ritual of walking, finding the lost, discarded, remnants lying the street, bringing them back to my studio and drawing them–each one tagged ‘I am still alive.’” Last year she did drawings Gather the Broken, each broken object drawn in conjunction with Amichai Lau Lavie’s commentary. Inspired by this work, Chassidic Pop artist Yitzchok Moully has been producing one abstract painting a day for this year’s Sefiras haOmer. The results have been intriguing and impressive.

Moully is a Chabad rabbi in New Jersey who has been exhibiting his Pop Art inspired canvases since 2007. While the Abstract Omer images, each 12” x 12” acrylic on canvas, are his first fully abstract series, his earlier works of Jewish themed images feature similar bright colors and heavily symbolic approaches to subjects. Moully is deeply at home with the volatile mix of kabbalah, personal introspection and abstract painting. These works have been featured on the Huffington Post’s “live Omer counting blog” and are a significant example of the spread of Judaism’s esoteric explorations.

The underlying theme of his Omer Map is that by becoming conscious of the sefirot of each day and concentrating on its two qualities of the Divine, one can apply such a meditation to one’s personal growth, daily becoming more complete as a human being and refining ourselves in preparation to receiving yet again the Torah at Shavous. As I write this, the Omer Map is not yet finished, being a work in progress.

The 7 weeks are arranged vertically, advancing right to left. The artist has followed the Rabbi Yitzchak Ginsburgh’s understanding of the Zohar in assigning each sefirah a specific color; for example allowing the white of Hesed to arrange a vertical collection of the first week, all utilizing a background of white. Each day’s permutation is made up of that week’s “foundation,” abstractly relating to the color of the daily influencing sefirah. In making Malchus a combination of all the preceding colors, Moully correctly expressed its traditionally designation as blue and black.

The first thing one notices is the enormous variety of his abstractions, especially considering the restraints placed on his use of color by the predetermined color assignments of the Zohar. He has painterly abstractions, color-field abstractions and graphic abstractions. Additionally he has posted textual meditations on each day that appear as you place the cursor over each image. These are usually 2 sentences that examine the relationship of two basic sefirah qualities and frequently challenge the viewer to examine their current behavior and possible improvement. While Moully’s texts are loosely based on Simon Jacobson’s books as well as weekly omer thoughts of Rabbi Mendy Herson, his own voice comes through especially in light of his abstractions. Day 19 is Hod of Tiferet, meaning Humility of Beauty (authenticity). Moully’s text advises us “to be authentic to our inner voice, our guiding principles, but it must include humility… we are not better than another because of the good we do…” The painting’s yellow (beauty / authenticity) is struggling with an invasion of orange (humility) that threatens to take over, even sometimes mixing with the beautiful yellow. The abstraction is in fact a struggle that reflects the tension between these two essential qualities.

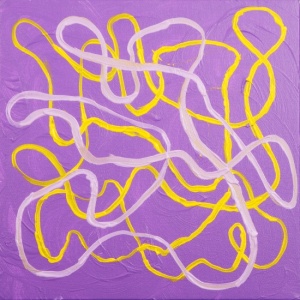

Day 24 is Tiferet of Netzach, meaning Beauty of Victory/Endurance. The text claims that “authentic (beautiful) endurance demands being true to yourself over the long haul. Endurance is not for the sake of endurance, but because it is a tool to expose the real you. Be authentic in your endurance–all the time. That is the challenge.” This painting presents a complex version of this aphorism. The impastoed violet background (victory/endurance) forms a foundation for the lyrical yellow (beauty) calligraphy that dances on its surface. But then another layer of broader light-violet swirls traps the yellow, providing a kind of ultimate victory of endurance and strength. In its abstract way the painting is pointing to a perhaps inescapable reality not easily overcome.

By adding the “language” of the visual to the dynamic of divine qualities and personal introspections, Moully has opened a complex and creative door to the daily process of counting the omer. While not all of his abstractions were equally successful and double worded translations are a challenge, there is no doubt that the attraction of a lush visual field definitely made the daily omer more engaging. The very struggle to unpack the riffing symbols of different color combinations played out against esoteric kabalistic concepts demands a concentration and immersion easily worthy of the biblical mitzvah.

Additionally this complexity seems to address the original question of why we were commanded to count 49 separate times in the first place. The repeating 49 mitzvahs demands that we delve into their very complexity, now recast in a visual exploration. Moully’s Abstract Omer paintings opens that enormously fruitful door.

www.moullyart.com