Zaslavsky’s Jews

Jewish artists do the darndest things. The Chassidic Art Institute, expertly directed by Zev Markowitz, is currently showing Venyamin Zaslavsky, a Ukrainian Jewish artist who has devoted the last 20 years to depictions of pious Jewish life in Jerusalem and the Holy Land. Considering his own homeland, the Ukraine, and its historic prejudices, his choice of subject matter is counter-intuitive at best. And yet Jewish artists do the darndest things.

Zaslavsky was born in 1936 in Kiev, the Ukraine. After the war he attended the Ukrainian Academy of Arts and mastered the deeply conservative and academic approach to the visual arts still prevalent under Stalinist socialist realism. As a result of his education and his innate creativity from 1967 until 1991 he was the principle artist of the Kiev Opera Theater creating costumes, sets and theater designs for more than 70 productions. Additionally he taught theater design at the Kiev Art Institute, produced numerous Ukrainian landscapes and was a member of the Ukrainian Union of Theater Arts. He was, by all accounts, a great success.

And then in 1991 he started creating paintings focused on pious Jews depicted in Israel. Perhaps the two most reviled subjects possible in his native Ukraine. And yet Zaslavsky persisted. It should be noted that the date of Zaslavsky’s artistic reawakening also coincides with the demise of the totalitarian and anti-Semitic Soviet Union and the relative freedom under the subsequent independent states. And yet this does not explain his radical shift in subject matter. Just because a subject became marginally permissible does not explain why he delved headlong into Jewish subjects. Rather one can only assume deeply felt issues of the heart and soul that demanded expression and simply could no longer be suppressed. Zaslavsky yielded to his Jewish passion and threw caution to the winds.

The current exhibition at CHAI provides a sampling of his recent work that reveals important insights into this neglected 75 year-old artist. His scenes of Jerusalem predominate with the Western Wall crowds, Bar Mitzvahs, colorful back alleys and side streets well represented. Over the years he has represented other parts of Israel including Safed. The defining element in almost all these works is the presence of religious Jews, usually Chassidim, with children. In fact children are everywhere.

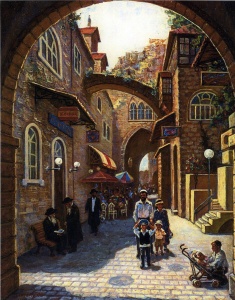

Beit Berger, a large Satmar cheder in Jerusalem, is lovingly depicted in Zaslavsky’s painting as literally overflowing with children. A group of boys are being escorted by two teachers and a woman down the stairs and into the courtyard in front of the school while a host of their classmates watch them from the balcony above. Some of them are gesturing through the railing while others have settled down with their tiny feet sticking through the same railing. One can almost hear the cheerful din of happy children. In a major compositional motif the movement in the painting begins up in the crowded balcony, moves down the stairs and then follows still more children as they walk under the archway and back into the painting; finally up the steps to a waiting group of older boys. In what is practically a “portrait” of this institution, the variety of clothing and mix of different kinds of people on the street, even including a woman who is simply out shopping, is refreshing insight. And while it is almost certain that this painting, as with many others, was done from photographs, the artist has taken great care to compose all the figures into small groups that relate to one another in a well-organized organic flow.

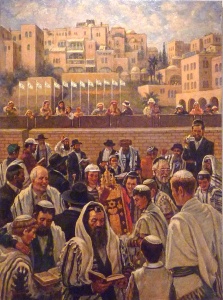

The same compositional care is taken is his iconic Western Wall that shows no less than 150 people praying, visiting, coming and going throughout the Western Wall plaza. The greatest concentration of figures is predictably in the men’s section right in front of the wall. Spreading out from there across the plaza are various groupings; three Chassidim clad in streimels and talleisim stride towards the entrance, two black hats in the foreground likewise approach while numerous men walk away with one, two or more children in tow, some with strollers, others escorting what seems to be a class of kids. Brightly dressed tourists observe the crowd and right in the middle we can make out a man photographing his family with the Wall as holy backdrop. And in a polite gesture to Jewish sensibilities, the artist has even removed the troublesome Dome of the Rock Mosque. For all of its “realism” we can observe that the image was taken from an older photograph since it shows the old earthen ramp to the Temple Mount itself that collapsed in 2004 and was replaced with a temporary wooden structure.

A quick survey of Zaslavsky’s paintings in the last decade shows his continual fascination with the Old City. The Jaffa Gate provides a backdrop for many themes including Chassidim dancing, strolling; coming and going. A tourist camel ride is likewise juxtaposed with the famous landmark as well as a beautiful rendition of palm trees shading a family picnic. While many of these works are clearly aimed at the tourist trade and armchair-bound nostalgia seekers, they all possess a charming sincerity as well as a deft sense of composition, color and light. As an expression of their charm and humor another painting features a Bar Mitzvah at the wall, faithfully being videotaped by a Yeshivish family member. The artist carries his art’s religiosity with a sensitive and light touch.

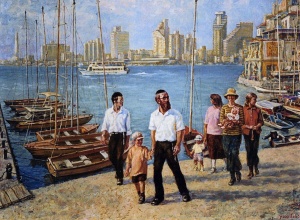

Significant also is Zaslavsky’s somewhat expansive vision of orthodox Jews in their dress and actions. While almost all the principle actors in his paintings are clearly religious, a painting of two couples visiting the Jaffa waterfront is refreshing in its modernity. The Yeshivish husbands contrast with the bobbing sailboats and Tel Aviv’s modern skyline behind them. Their wives and a friend following are stylishly dressed in a way that also firmly roots these Jews in the contemporary world.

Other subtle examples of modernity are found in one of his recurring Old City images. Old City Stroller is full of predictable charm; time-worn stone facades and arches shelter an outdoor café, Chassidim chatting in the shadows while a young family with two children approach a stroller and a young man taking care of an infant. The stroller, in the context of this sentimental image, is itself unusually modern, clearly not a traditional baby carriage. But the yellow and red Kodak sign unmistakably roots us in the late 20th century.

Equally part of the legacy of the 20th century is the curious phenomenon of Lubavitch weddings in front of 770 Eastern Parkway. A good Lubavitch friend of mine informed me that “The minhag of holding weddings at 770 began sometime in the mid 1960s. By that time, the Rebbe’s schedule became so hectic that the only way for him to logistically serve as Mesader Kiddushin was if the wedding was held in front of 770. It was not long after that that the Rebbe stopped being Mesader Kiddushin altogether, but the custom of holding weddings in front of 770 has remained ever since.” And lo and behold, Zaslavsky decided to make a painting of exactly that. 770 Wedding is a pictorial document in which the place, 770 Eastern Parkway, is pictorially as important as the huppah and wedding party below. The bride is joyful and all the men in the wedding party are happy and satisfied at this blissful event. A smattering of girls and boys and young women complete the foreground of the celebration.

Zaslavsky has spent a substantive amount of his creative career looking into the heart and soul of the religious Jew’s world. He depicts this world with empathy and concern, never flinching from its modern trappings and complications. Indeed its modernity and contradictions are inevitably bound up in his realistic academic matrix, expressed in contemporary images that confront tradition in totally unexpected ways.

Such is the reality of the Jewish artist. They create the darnest things.

Zaslavsky’s Jews

Chassidic Art Institute

375 Kingston Avenue

Brooklyn, New York