Yad Vashem’s Art

Obscenity is not the usual province of art. And yet behind almost all Holocaust art lies the obscenity of the crime, the stench of genocide. This simple fact makes it singular in the history of art, a deep contradiction of art’s traditional civilizing role even as its horror fuels the artwork with power and urgency. We cannot afford to ignore it.

Yad Vashem, the preeminent memorial and museum of the Holocaust in Jerusalem, has opened a Museum of Holocaust Art as part of its massive renovation that was formally dedicated on March 15, 2005. The new art museum covers the years from 1933 until 1947 while Holocaust art produced after that is seen in the adjacent Exhibition Pavilion. The scope and scale of this undertaking is unheard of within the world of Holocaust museums and memorials. It implicitly recognizes the central role that art played in reaction, protest, survival and continued recognition of the Holocaust as the epochal event of our time. Situated immediately at the end of the central exhibition area, this collection, only a fraction of Yad Vashem’s vast holdings in artwork, emphasizes the important ways culture can begin to understand the Holocaust.

Moving through the exhibition certain artists emerge as familiar voices. Charlotte Salomon (Jewish Museum retrospective, March 2001) is featured in a major exploration of her landscapes from 1939-41 done while fleeing the Nazis in southern France. Her better known work is obsessively autobiographical and wildly idiosyncratic while this selection establishes her as an artist of considerable skill and abstract aesthetic sensitivity. Her murder by the Nazis and our loss seems even greater. Arnold Daghani’s Portrait of Musia Korn at Age 18 is a hauntingly stark graphic image that nonetheless preserves a fine tuned aesthetic. Later in the exhibition Daghani’s One of the Five Tailors from the Bershad Ghetto in 1943 utilizes the tools of a fine artist to bring to life the cramped, mean and oppressive world of the ghetto. Bruno Schultz, who would be murdered by an SS officer in 1942, exposes the roots of societal breakdown that predate the Nazis by at least a decade in The Enchanted City II (1920-22), a Goyaesque vision eerily prescient of the obscene decadence to come.

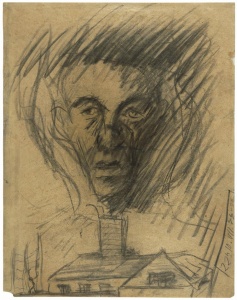

Inmate art is particularly harrowing because of the terrible proximity to the machines of death. Nonetheless, Bedrich Fritta displays a consistently calm visual intelligence, his closely observed views of walls, gates and barracks of Terezenstadt bringing seemingly innocent structures to life as oppressors and portents of what awaited the inmates of the “model camp.” Yehuda Bacon memorialized the Czech transports to the gas chambers in an image of a ghostly head that appears rising from a chimney. He survived and went on to teach at Bezalel Academy in Israel. This drawing was done when he was a sixteen year old inmate.

The subject of religion in this obscene landscape is unflinchingly explored in a few important images. Zinovii Tolkatchev’s Taleskoten (1944) is an iconic image of a tallis katan caught on a barbed wire fence, fluttering in a ghastly breeze, emblematic of the destruction of Eastern European Jewry. It appears as the tattered flag of religiosity accusing God of leaving mitzvahs unrewarded in this world. As part of the Soviet liberating army (he was official artist of the Red Army) Tolkatchev drew some of the most graphic images to emerge from the camps. They will Never Fall Silent (1945) is a quiet document (drawn on Auschwitz kommandant stationary) of suffering at the gates of death.

Felix Nussbaum is a major presence and his Camp Synagogue (1941) remains one of the most disturbing images of his oeuvre. Repeating motifs of three (strands of barbed wire; a bone, a can, a boot and three of five figures in striped tallis, two bare headed and one covered) locks us into a morbid dance of irony, questioning how faith can survive as the prisoners trudge towards a tin roofed shed for morning prayers.

An unexpected revelation is the large selection of Biblical images by Carol Deutsch done between 1941 and 1944. This artist, greatly influenced by the 19th century William Blake, possessed an obsessive vision of biblical narratives featuring innovative aerial perspectives (In the Tabernacle) and strangely inventive visions of Pharoah’s daughters (And When She Saw the Ark) as 1930s maidens. While his work is ultimately too sophisticated and predictable, his images by their sheer presence nonetheless challenge Nazi totalitarianism.

Isaac Celnikier addresses the silence of God in Et vous Dites Que Dieu Est Absent ! of 1946. Over ten years later he continues a similar exploration in Ghetto with Angel (1958-64). This large work, unfortunately tucked away in an auditorium, summons the shock of Manet’s Execution of the Emperor Maximilian with figures on the right taking deadly aim at a couple cowering on the far left. A winged angel interposes itself between the victims and the executioners. While the work feels episodic it still carries tremendous power in its starkness, passionate paint handling and sheer scale that presumes the presence of angels (metaphorical or actual) in the death throes of the ghetto.

The very obscenity of this subject matter has a hypnotic effect on those touched, burrowing into the soul of those unfortunate enough to expose their emotions to what for most of us is incomprehensible. Zoran Music survived the camps and did drawings of inmates dead and dying. Twenty-five years later he returned to the subject with an important series We Are Not the Last (1970). The same images are revisited and, in a heartbreaking and passionate manner, repeated to explore what may be characterized as a symphony of death. Natan Nuchi, son of a survivor, is represented by a digital image of a figure in a vast field of visual static, a cacophony of meaninglessness (Untitled, 1997) that is representative of an obsessive body of work this artist developed over close to 20 years. Naftali Bezem worked on Jew Digging His Own Grave (1955), changing, adding and subtracting, until the image conveyed just enough horror to allow letting go of it.

As artists began to move away from the absolute reality of mass murder, metaphor became an important tool to approach the subject. Rosemarie Koczy’s three drawings from the series Je vous tisse un linceul (1996) depicts single figures, bent over, twisted and crouching. It would feel expressionistic if they were not so convincing in evoking the suffering each victim felt in the struggle to survive. The obscene distortion of that which is so uniquely human makes the suffering relentless, uncertain that death would suffice to end it. Similarly Menashe Kadishman’s Falling Leaves (1997-2001) presents us with an unacceptable view of Jewish slaughter. Individuals, each with their own hopes, dreams and lives are reduced to anonymous ciphers. The very weight of the rusted cast iron makes it difficult if not impossible for us to move past them or help them. The victims of the Holocaust will not go away, we cannot avoid them and yet we cannot redeem them.

The Museum of Holocaust Art at Yad Vashem brings us within an uncomfortable proximity to many of the underlying issues of the Holocaust. It is hoped that its scope and dedication may harken to a new era in which Holocaust art takes its place among the seminal cultural expressions of our age, guaranteeing that neither Jew nor Gentile will ever forget.