Unconditional Love: Cairo Ark Door and Falk’s Paintings

Unconditional love is a concept that sets the bar of human conduct and forgiveness at a dizzying height, challenging the very fabric of human credulity. The same stress exists when applied in a religious context, fueling extreme expectations of the Divine/Human relationship. In a rather curious and unexpected parallelism two current exhibitions express and explore aspects of unconditional love, each with surprising results. While Yeshiva University Museum’s exhibition of the Ark Door from the Ben Ezra Synagogue reflects that community’s steadfast loyalty to living in the “forbidden” country of Egypt, so too does Alan Falk’s pictorial exploration of the Song of Songs and the Dybbuk proclaim their respective unconditional and undying love.

Threshold to the Sacred, curated by Dr. Jacob Wisse (Yeshiva University Museum, Director), is ostensibly about the historically remarkable wooden Torah Ark door that has been traced to the 11th century ark of the Cairo Ben Ezra Synagogue, likely in use when Maimonides frequented that house of worship. However in reality the exhibition examines the larger Jewish community of Fustat, now known as the medieval center of old Cairo. The diverse complexity of this diasporic Jewish community is brought to life by a host of ancient objects and documents, many of which were retrieved from the famous geniza found within the Ben Ezra Synagogue walls. Their place in Jewish history is unique in its halachic tension, achingly poised between cultural diversity, transgression and praise of Hashem.

The community of Fustat, which dates from the 7th century C.E., (the beginning of the Islamic presence in Egypt), proudly associates itself with the Exilarchs of the Jewish diaspora as evidenced by a detailed genealogy from the Cairo geniza tracing their lineage back to King David and Adam, the first man. Perhaps equally significant is the persistent notion that the Jews who lived in Egypt were proud to be living at the site of the great miracles of the Egyptian exodus, an idea expressed in the poetry of Yehuda haLevi. (Could this have required them to recite the special blessing for seeing a place where our ancestors were blessed with a miracle?) In our twice-daily remembrance of the Egyptian exodus in the Shema, conceivably we should fondly remember Fustat where our brethren lived on the shores of the Nile for close to 800 years. Of course there is a serious flaw in these splendid notions.

The Torah explicitly prohibits returning to Egypt in three verses: Exodus 14:13; Deuteronomy 17:16 and 25:65; “You shall not see Egypt again.” The Gemara, Succah 51b, recounts the terrible consequences of one such communal transgression, the annihilation of the Alexandrian Jewish community by the Roman Emperor Trajan in 116 CE. In spite of the many attempts at explaining how Torah giants such as the Rambam and the Radbaz could in good conscience reside in Egypt, the tension between the reality and the halacha remains. It was expressed by the Rambam himself (1138-1204) who spent the last 40 years of his life in Fustat and who allegedly signed his name; “Moshe ben Maimon, he who transgresses the prohibition ‘You shall not return on that way anymore.’”

Notwithstanding the Torah injunction, the Egyptian community thrived and became an international center of trade, especially under the Fatimid period (909-1171). The diversity and excitement of that period is revealed in period documents from the treasure-trove geniza itself. Both the Rabbanite (reflecting the Talmudic rabbis) and the Karaite (rejecting the normative authority of the rabbis) factions of the Fustat Jewish community are well represented in geniza documents, reflecting a united Jewish community that nevertheless maintained separate synagogues. Additionally, the Rabbanite community was composed of Jews that followed the customs of Babylonia and those who followed the customs of Palestine (such as the Ben Ezra), each with their own synagogues. Even a casual perusal of these incomparable documents reflects the permeability of a highly diverse Jewish community. Proudly positioned in the midst of this Jewish diversity stands the Ark Door itself.

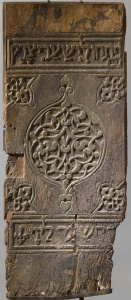

The wooden door, the only one surviving from a pair, measures 34” X 14” X 1” and has been scientifically dated to the 11th century when the synagogue underwent a major renovation. Based on visitors’ descriptions, this specific door was in use well into the 19th century. It was jointly acquired by Yeshiva University Museum and the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore in 2000 and has been under conservation and research at the Walters Art Museum since then. The verses carved top and bottom from Psalm 118: “Open to me the gates of righteousness,” and “This is the gate of the Lord,” also likely date from the 11th century (based on the particular abbreviation of God’s name used here), while the central abstract design was almost certainly created hundreds of years later from 14th century Islamic book design.

Another fascinating detail is the back of the door, also elaborately carved with a ‘spinning’ decorative design, but here adorned top and bottom with the Birkat Kohanim. Evidently there is a Sephardi minhag of allowing the aron doors to remain open during the birkat kohanim: thereby in this scenario allowing this verse to face the congregation when the kohanim are actively blessing them. This detail suddenly brings us into the actual use of the ark door and, with a little bit of imagination, into the middle of a morning service.

The objects and documents of this exhibition, a small selection reviewed here, convincingly bring alive the Fustat community and its larger environs. They express their unconditional love of serving God and His people; forever reminded, no matter how harsh the current conditions were, of Egyptian bondage and ancient Exodus that occurred in their hometown.

Alan Falk has a significantly different understanding of unconditional love in his current exhibition of paintings and watercolors depicting the “Song of Songs” and the “Dybbuk” currently at the Jewish Religious Center at Williams College. His approach to Song of Songs concerns the “romantic and magical aspects of love” that he finds in the fabled poem that is “a universal love story about the awakening and consummation of love between a youthful shepherd and a young Shulamite woman” [All quotes are from the artist’s catalogue introduction]. This of course flies in the face of Rabbi Akiva’s injunction that while; “The entire universe is unworthy of the day on which the Song of Songs was given to Israel. All the Writings are holy, but the Song of Songs is the holy of holies…” (Yadaiim 3:5) therefore, “One who recites a verse of the Song of Songs and renders it a kind of (ordinary) song…brings misfortune to the world” (Sanhedrin 101a). Rashi went so far as to translate the Song in totally allegorical terms solely expressing the constant and undying love of God for Israel.

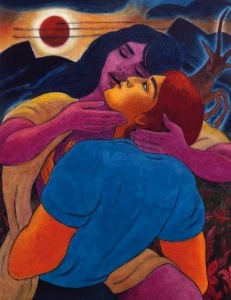

Nonetheless Falk has based his illustrations on a contemporary secular translation by Chana Bloch and Ariel Bloch, striving to evoke a vision of “unconditional love and a harmonious relationship between us and the natural world…[that] can be a holistic path to healing our world.” While the twelve watercolors he shows here are but a selection from an ongoing series illustrating the entire poem, I would imagine they are representative of his goals. Both the shepherd and the Shulamite are featured together in all but three of the images, almost always locked in variations of a loving embrace. While this might be expected, the theme of longing, so dominant in the poem, seems missing. When the Shulamite is featured alone, she is a direct reflection of the poetic verses: i.e.; “Who is that rising from the desert like a pillar of smoke…” we see the female figure encircled by smoke rising from the sandy desert; “An enclosed garden is my sister, my bride…” shows a modest woman kneeling in an orchard. This reflects the fundamental problem of attempting to make art from already existing art, i.e. the inherent poetry of the Song itself.

Falk’s choice of graphic novel techniques; utilizing mostly flat color with little modulation, highly cropped images replete with explicit pictorial symbols unfortunately tends to deplete the poetic potential of the visual medium, trapping the images in an illustrational mode. Paradoxically in a poem known for its strong female voice, at least some of Falk’s images betray a male gaze, subverting at least one aspect of unconditional love desired.

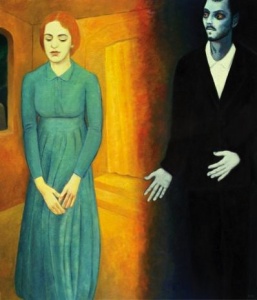

S. Ansky’s The Dybbuk, or Between Two Worlds: A Dramatic Legend in Four Acts (1912-1917) presents a radically different prospect. While the tragic tale of two lovers, Channon and Leah, has an infinitely more complex prelude than the figures in Song of Songs, most importantly the final consummation of their relationship, the dybbuk (Channon’s soul) fusing with the soul of his beloved, Leah, results in their mutual death. In its way this form of unconditional love leading to the ultimate “unity and shedding of duality through an act of love” is pure romanticism quite foreign to Judaism’s fervent affirmation of life in this world.

Falk’s four oil paintings from The Dybbuk successfully encapsulate the spirit of Ansky’s narrative, depicting the development of Leah’s character as it is affected by the tortured soul of Channon. The last painting shows them in blissful union soaring over the nighttime village synagogue in a spiritual “resurrection.” The scene in which the dybbuk within Leah verbally attacks the father of her intended groom is a nightmarish evocation of a schizophrenic episode. Equally unnerving is Leah’s tortured reclining on the graves of the ancient martyred lovers. In each of these images there is more than a little tinge of madness that permeates the drama. Most of all in the first painting: The Dybbuk: Leah and Channon, in which Channon’s first awkward confrontation with Leah from the shadows of the brilliantly lit shul, the haunted red-eyed gaze of Channon convinces us of the impossibility of a love unhinged and driven by totally external dictates (the irrational vows made by their fathers before they were even born). In these images Falk’s lurid color and illustrational style well serves the tragic narrative, driving home (perhaps paradoxically) the perverse consequences of untempered unconditional love.

Threshold to the Sacred: Ark Door of the Ben Ezra Synagogue, Cairo

Yeshiva University Museum – Center for Jewish History

15 West 16th Street, New York, N.Y.; (212) 294 8330

Sunday, Tuesday and Thursday: 11 am – 5 pm

Monday: 5:00 pm- 8:00 pm; Wednesday: 11 am – 8 pm

Friday: 11 am – 2:30 pm; FREE Monday, Wednesday (5 – 8 pm) and Friday

www.yumuseum.org : $8 adults, $6 seniors & students

Until February 23, 2014

Between Two Worlds: Alan Falk: The Song of Songs and The Dybbuk

Jewish Religious Center at Williams College, 24 Stetson Court, Williamstown, MA

Until November 30, 2013