Megillah Esther by David Wander

Such a nice story the Megillah Esther is, don’t you think? The poor Jews are in exile far from home and get into a bit of trouble with God for not being so careful about their kashrus. Their only sin was attending a treif banquet the headstrong King Ahashverous made for the whole kingdom. And then sweet but unlucky Esther gets rounded up and taken to be the King’s queen. Esther and a goy! Oh, my! What was poor Mordechai to do? On top of that the evil Haman gets in power and decides to kill all the Jews. Oh, my! Oh, my! Well, something had to be done and so brave Mordechai and Esther save the day, make the King see what’s what and everything ends happy and fine. What a nice story and we get to celebrate, eat, drink and dress up as Esther and Mordechai!

Not so fast. According to painter and book artist David Wander and his Megillah Esther, currently on view at the Hebrew Union College Museum, the tale is of starkly different proportions; dark, violent, forbidding and thoroughly modern. He has created an artist’s book that unfolds to a length of 55 feet and abounds in hangings and executions. The Hebrew text of Esther is embedded on rice paper and surrounded by a cacophony of images that interpret the grim terms of Jewish survival. We get to celebrate only because we have just escaped from certain death and have not been annihilated. Where the narrative takes us, and Wander’s images force us to recognize, is none other than the timeless confrontation with evil, there embedded in Haman, now seen in Hitler, totalitarian dictatorships and the Ku Klux Klan. They are all vicious and dangerous and must be annihilated before they can attack us. Blood must flow.

David Wander has been exhibiting his paintings and pastels for well over twenty years, producing intense color-filled landscapes and Judaica. Additionally he is a master printmaker and book artist. Notably his Holocaust Haggadah (1985) is found in many public collections and his Jonah Drawings (2000) have been widely exhibited and reviewed in these pages. His works are found in many museums including Yad Vashem, Jewish Museum, New York and Israel Museum, Jerusalem.

Most significantly Wander’s Megillah begins with a cover in low relief that depicts a black and white checkerboard. This motif permeates the 12 illuminated panels that follow, signifying that we are about to enter a deadly game, one in which there is a confusion of good and evil, God’s hand is hidden and nonetheless a game the Jews must win to survive.

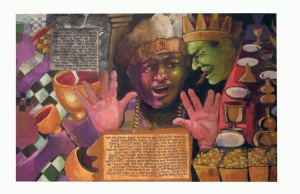

A title page of preliminary brochos establishes an ominous and threatening background of monochromatic Assyrian animal idols. The text begins surrounded by the foolish King Ahashverous wearing the tzitz (golden head plate), the word kodesh clearly upside down, and his hands in a mock priestly blessing. He shares his defilement of holy vessels with the sickly green-faced Memuchan, midrashically identified as Haman himself. The debauchery pervades the image in lurid color as the next panel depicts Vashti’s severed head, the checkerboard motif asserting the deadly machinations of royal power struggles. In a corrupt totalitarian state no one is safe from assassination.

The arbitrary nature of royal power is depicted in the next complex panels, first showing Esther crowned by an unseen king. Simultaneously the confrontation between Haman and Mordechai is contrasted with the two hanged conspirators who dangle over an open book, foretelling their pivotal role in the narrative. As the evil decree against the Jews is promulgated the checkerboard powerfully asserts itself, rectangles of text juxtaposed with playing pieces that rest uncomfortably on the lines, creating uncertainty as to exactly where the players have moved as the verse says, “The King and Haman sat down to drink; but the city of Shushan was bewildered” (3:15). The royal signet ring is given to Haman and destruction seems assured for the Jews.

A merciless grid of text and rectangular images reaches a fever pitch as Mordechai warns Esther “Do not imagine that you will be able to escape in the King’s palace any more than the rest of the Jews” (4:13). Her fate inextricably linked to her people, Esther must now navigate the maze of royal courts that we gaze into from above, seeing at the bottom the hand of Esther reaching out to the extended royal scepter, granting her audience with the powerful monarch even as a puzzled Haman looks on, wondering the meaning of three cups of red wine set out for the banquet to come. One will never be drunk.

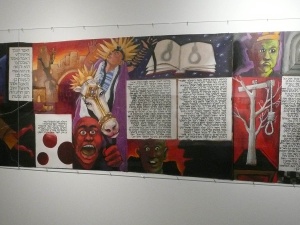

This panel is dominated by the tree bearing the hanging noose, quickly flowing into the next set of panels that bring us to the triumph of Mordechai. The tone of the images changes here, becoming simpler, more direct and palpably more terrible. The double shadows of the hangman’s noose now appears on the open record book, prelude to Mordechai’s honorific procession on the Kings’s horse. In Wander’s vision Mordechai is triumphant, hands raised in celebration and affirmation of his Jewish identity expressed in tallis and tefillin, the very straps of which that visually echo the ever-present noose.

In what is normally thought of the dramatic climax Wander seems to pull back. Queen Esther denounces Haman from the shadows and an unseen hand pushes the evil one onto the couch the queen rests on, further sealing his fate of hanging seen immediately next to the text that proclaims his demise.

The next four panels constitute a grim masterpiece, eerily bringing the narrative into the present, first with an elucidation of the transfer of power from Haman to Esther and Mordechai. The royal signet ring is removed from dead hand of Haman and given to Mordechai. Most significantly this transfer of power is shown in a series of seven royal seals, red wax impressed with the royal crown, each document splattered with the anticipated blood of the enemies of the Jews.

Mordechai presides over a field of upright knives and swords, surveying the slaughter about to commence in “royal apparel of blue and white with a large gold crown and a robe of fine linen and purple” (8:15). Many of the knives are already reddened with the victims blood in a stark and unforgettable image. This stands as a powerful introduction to the hanging of Haman’s ten sons, here seen as klansmen, all hooded now in death and removed from the terror they originally espoused.

In light of all this violent retribution never has a megillah ended so hopefully, enlisting a duet of Jewish symbols that assure a bright Jewish future. As the text panels now march to the conclusion a famous midrash is depicted within the text in a simple line drawing. It depicts the mountain that was suspended over the nation at Sinai, now lifted and symbolizing our acceptance of the entire Torah, reflected in the verse, “…the Jews confirmed and undertook upon themselves…” (9:27). A lone royal scepter (seen as a Torah pointer in the form of a hand) points to the inevitable result of Jewish courage, determination and submission to Torah; two Shabbos candles glowing brightly in the window of what can be none other than a Jerusalem home. The megillah has brought us in peace to our true home. And through David Wander’s Megillah we now know with certainty that this road is often uncertain, dangerous and violent. And since God’s hand will continue to be hidden, our faith and determination have to be all the stronger.

The Whole Megillah: New Images from an Old Book

Drawings by David Wander

Hebrew Union Collage – Jewish Institute of Religion Museum

One West 4th Street, New York, NY