The Problem with God

The problem with God is His holiness. After thousands of years of countless trials and many too many unmentionable “sufferings of love” (Berachos 5a) the Jewish people continue to love Him even as many flee His embrace. From the Binding of Isaac to the martyrdom of Rabbi Akiva and the last Jews of the Warsaw Ghetto, God’s seeming distance, his hester pannim, confounds the masses and sorely tests the pious. When He is the most distant, and therefore the most Holy, the slaughter of innocent Jews that ensues becomes tragically a chilul Hashem, defaming his holy Name.

Yossel Rakover Speaks to God by Zvi Kolitz and Death Triumphant, a painting by Felix Nussbaum, both struggle with this most perplexing issue of the Jewish people. The first, a short story purporting to be a last testament of the son of a Ger Hasid fighting in the Warsaw Ghetto, refuses to relinquish belief in God. His experiences as a hunted Jew, a survivor from a German air assault that killed his wife, infant child and two children to the terrible depravations of the ghetto that claimed his last three children has left him spiritually exhausted, proclaiming that; “Life is a tragedy, death a savior; man a calamity, the beast an ideal; day a horror, night—a relief.” As a man of faith the cruelty he has suffered has turned all certainties upside down. He lashes out at the world that seems determined to annihilate him.

Yossel’s accusations encompass Western civilization, bitterly observing that Hitler is “a typical child of modern man. Humanity as a whole has spawned him and reared him, and he is the frankest expression of its innermost, most deeply buried wishes.”

At forty-three he humbly states that he “served God enthusiastically” only asking to worship Him, “bikhol livovekho, bikhol nafshekho ubikhol miodekho.” After all his deprivations and sufferings his belief has remained unshaken even though his relationship with God is deeply compromised. He feels that God “owes me something, owes me much.” Claiming that to cite our sins as a reason for this suffering, “God is maligned when we malign ourselves.” After all, we are his people and when God’s people suffer, God’s name is besmirched.

In his last moments Yossel reflects upon the nature of vengeance, both human and Divine, the very nature of being a Jew and finally the excruciating nature of choseness. He is the last fighter alive in one room in one house in Warsaw in 1943. His desperation elicits a proud affirmation; “I believe in Israel’s God even if He has done everything to stop me from believing in Him,” adding that “I bow my head before His greatness, but will not kiss the rod with which He strikes me.” The courageous determination to demand to know when “You…again [will] reveal Your countenance” is unequaled in Holocaust literature.

Mark Altman’s English and Yiddish production of Yossel Rakover Speaks to God (staged reading at the Diaspora Drama Group) on June 7th will explore exactly these excruciating themes. The poignant voice of Yossel will ring out that evening, a seminal testimony and clarion call from the grave of sixty-five years ago. Except for the fact that Yossel is a fictional character created by Zvi Kolitz. This character, invented by Mr. Kolitz for a Yiddish newspaper in Argentina in 1946, took on a life of its own. The story was subsequently published in English and Hebrew without any attribution to Mr. Kolitz and became known as an anonymous testimony from the ashes of the Warsaw Ghetto. Fiction had taken on a life as its own, as Emmanuel Levinas commented; “a text both beautiful and true, as only fiction can be.”

Felix Nussbaum traveled a remarkably similar path to a distinctly different conclusion. Nussbaum was born in 1904 in the German town of Osnabruck. He was characterized from an early age as a depressive personality and pursuing his artistic studies his early work was occasionally characterized by a haunting presence of impending death. The Nazi ascent to power spelled the end of Felix’s aspirations to German artistic achievement. His work from this decade vacillates between a kind of primitive and acerbic social commentary and a more than competent 1930’s realism. His increasing use of symbolism reflected the devastating advance of fascist control across Europe even as he attempted to escape its jaws by emigrating to Switzerland and finally Belgium in 1937. More and more Nussbaum utilized masks and self-portraits to reflect and deflect the impending doom.

Nussbaum, along with his wife Felka Platek, were exiles, refugees from their native land and, more importantly, refugees from the sanity of their past. His art became the art of the refugee; haunted, despairing and wrenching. In 1940 he was arrested and interred at the camp of Saint-Cyprien for four months as a German national. During a selection between Aryan Germans and Jews, he escaped and fled through France to his wife in Brussels, Belgium. The camp, its inmates and horrors became an unavoidable subject for Nussbaum.

Aside from depicting the all too familiar deprivations of internment camps, Nussbaum did a remarkable painting of Camp Synagogue in 1941. It is a deeply brooding meditation on the repercussions of Jewish faith by an artist whose closeness to Judaism seemed to be mainly enforced by the racism of Nazi rulers. Five men, all clad in talisim, trudge towards a tin roofed building under a dark and foreboding sky. One man is isolated even from his fellow Jews, hunched in solitary devotion, perhaps the symbol of the artist himself.

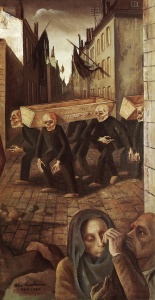

As a stateless person and a Jew, his status in Belgium deteriorated in 1942, a rope hanging appearing as a symbol of approaching doom at the hands of the occupying Gestapo. In 1942 Nussbaum is given refuge by a Belgian sculptor until he flees underground. Finally in 1943 he and his wife go into hiding. The Organ Grinder (1943) begins the paintings in which the figure of Death has assumed prominence. The Damned, painted in January 1944, depicts a hodgepodge of hidden Jews, now terribly exposed for deportation in the claustrophobic streets of their country of refuge. It has become increasingly obvious that there will be no escape.

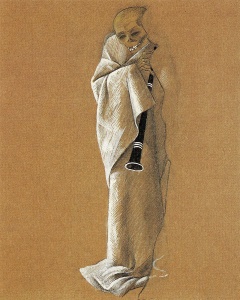

His last painting dated Tuesday, April 18, 1944, Death Triumphant, is extensively prepared for with numerous sketches of various skeletal figures, each beautifully draped, playing or holding musical instruments. These drawings are arguably some of the most moving and devastating images of futility ever produced. The dead mock the living with mankind’s pathetic culture, music played with no one left to listen. The quest for life is snuffed out in the whirlwind of anti-Semitic hate.

Felix Nussbaum confronted God’s terrible hiddenness just as Yossel did. Felix could not find a faith to express in his vision, only Death triumphs over all culture, all hope, all life. And yet Yossel knows Felix well. Addressing God, Yossel pleads “Do not put the rope under too much strain, because, God forbid, it might snap. The test to which You have put us is so severe, so unbearably severe, that You should—You must—forgive those of Your people who, in their misery and rage, have turned away from You.”

The problem with God is that in His awesome holiness He has given us a terrible choice. Do we act rationally and turn our backs on him when he seems to abandon us? Or must we scream through the howling abyss and insist on His answer even as the silence engulfs us?

***

Zvi Kolitz, author of Yossel Rakover Speaks to God, passed away September 29, 2002 after an illustrious career as a film producer (Hill 24 Doesn’t Answer, 1954, Israeli film) and theatrical producer (Rolf Hochhuth’s ground breaking play, The Deputy, 1963) in addition to works of fiction and philosophy and 32 years as a columnist for the Algemeiner Journal. Felix Nussbaum was murdered with his wife in Auschwitz in August, 1944.

Yosl Rakover Talks to God by Zvi Kolitz, Vintage, 2000 (with commentaries by Paul Badde, Leon Wieseltier and Emmanuel Levinas)

Yosl Rakover Talks to God; A Reading produced by Mark Altman, Tuesday June 7, 2005

The Diaspora Drama Group at Common Basis Theater; 750 Eighth Avenue (46th Street); 212 868 4444; www.diasporadrama.org

English version directed and performed by Tony Award Winner Vivian Matalon; Yiddish version with David Mandelbaum directed by Amy Coleman

Felix Nussbaum: Art Defamed, Art in Exile, Art in Resistance: A Biography edited by Karl Georg Kaster, Rasch Verlag, Bramsche, 1994