The Paintings of Leah Ashkenazy

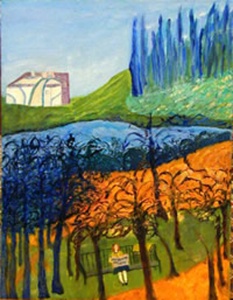

You see, there is just something about that little girl that I can’t get out of my mind. How does she face those fire-breathing beasts? Her certainty shakes me and leave me sleepless. Is it because the two monsters threaten the funny little house with the all-seeing eyes and yet mysteriously ignore the little girl. Again the little girl. How can she calmly walk in the field, just off the road yet, and not run from the terrible monsters that hover over her?

The paintings of Leah Ashkenazy haunt me with questions. And perhaps most importantly, they are the questions that are among the most important questions to ask. But even more significantly, they offer glimpses of answers gleaned from a lifetime of living. Leah Ashkenazy was born in Rumania and lived her childhood there throughout the war. Now, so many years later, she lives in Borough Park, a widowed grandmother who delights her grandchildren with the strange and amazing paintings she has been making for the last four years.

This painting, The End of Childhood, is a complex commentary on the Shoah and how it effected the children that lived through it. It contains a child’s perspective without being child-like. The Nazi killing machine is depicted as mythical beasts, awesome and, paradoxically, silly at the same time, much like goose stepping soldiers.

Nonetheless, it is fearsome, breathing fire that has consumed the city on the left with the crying souls floating up in the billowing smoke. In this vision of destruction every element is animated since every element in this life has meaning and content. And just as the house that is about to be destroyed, was destroyed as were the thousands of Jewish homes and wooden synagogues and are gone forever; so too the little girl, as did some little girls and boys, survived. Poignantly, the painting raises the terrible questions of those who happened to survive. Why did some survive? The artist answers by devoting her artistic work to telling her grandchildren. It is clear that they must know.

Ashkenazy tells us how a survivor becomes aware of the terrible history that occurred around her in May 1944. She sits on a park bench and reads a newspaper that proclaims: “Nazi Gas Six Million Jews.” The beautiful lush park is singular for its denuded trees. It is calm and she is alone. Above her stretches a wonderful landscape; a lake, fields, an idyllic mountainside lined with elegant blue trees and a fantastic structure awaiting inhabitants. Are we looking into a heavenly future or a Europe empty of its Jews?

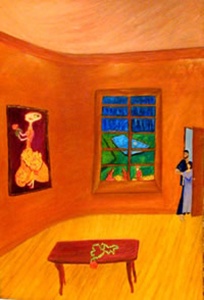

In Leah Ashkenazy’s paintings the future is lived out in her visions of the lives of her children and grandchildren. The Necklace presents a young couple peering into an enormous room. It contains a large modern painting on one wall and a table in the middle of the otherwise empty room. On the table there is a mysterious green necklace with an orange pendant. This is the precious inheritance for the young couple and the three children playing outside the window. The drive to make Art and the precious jewels of a poetic vision are perhaps why some survived. Still, such answers, even when offered, remain elusive.

Even more elusive is this grandmother’s cry; Where are the Children? The title evokes the fear and horror of the war years and yet is transferred to the security of her house in Borough Park. It is a bright fantastic vision of the interior of grandmother’s house, the patio doors opening on to a spring afternoon. The interior is adorned with a lush crimson carpet and the walls with her paintings. And where are the children? They are just glimpsed playing, perhaps even flying, through the skylight above. It is precisely this kind of playful suspense that Ashkenazy works so well. The strong bold compositional elements such as the dominant yellow walls that run straight across the painting are pierced by the patio doors, the skylight and the illusionistic paintings. Are they paintings or perhaps also windows into another world? Each of these elements challenges the reality of the wall existing in space. Her skillful combination of abstract design, evocative images and challenging titles creates an interior narrative that continues to draw us into the world and drama of these paintings.

Finally, Leah Ashkenazy is a teacher of Torah. In the largest sense that the history of the Jews is also Torah and in the more specific meaning seen in The Saving of Moses. Here Batyah, Pharaoh’s daughter, is the main character. She has rescued Moses from the waters of the Nile and holds him in his basket possessively perched atop her head. The determined look on her face reveals that she seems to sense his destiny, emphasized by the tablets of the Law that just happen to line up right above her head on the horizon behind her. We see Miriam and another family member gesturing helplessly on the distant shore. This wonderfully fresh Biblical painting, rendering a simple landscape and straightforward figures clad in contemporary dress brings us again to the current scene. Could it be that the Jews needed Batyah, a non-Jew, to help start their redemption? Sometimes, whether as children or as helpless adults, we are cast adrift and need the help from the righteous among the nations.

Leah Ashkenazy only recently started making paintings. Before then she had raised a family, went to college in her forties, majored in Comparative Literature, wrote extensively and got a Masters degree from Brooklyn College. And then a chance encounter led her into painting. She studied with Chava Roth (reviewed in this column last year) in Borough Park and with Larry Poons and Philip Sherrod at the Art Students League. Her teachers have been excellent, especially since they consistently advised her to focus on and develop her very special vision. But her vision is more than just “special” in a simply personal way.

The twentieth century has been a horror. The defining moments for the Jews have been the merciless slaughter of the Holocaust and the rebirth of a vibrant Jewish people out of those ashes in the creation of the State of Israel and in the Diaspora, even in the face of rampant assimilation. Leah Ashkenazy has taken the Holocaust and its aftermath and dealt with it directly and creatively. Unflinchingly. This is something almost no other artist has been able to do to date. She says she paints two kinds of paintings: tzuris and grandchildren. I would respectfully differ with her. Rather what she paints is the survival of our people in the one place it matters. The Jewish family. The answer is in the grandchildren, all our grandchildren. Now I think I can understand how that little girl in The End of Childhood can walk so calmly beneath the beasts. She knew she would grow up to become a mother and then have grandchildren. And she would paint them wonderful pictures of how it was and how it will be for the Jewish people.

Published in The Jewish Press