The Braginsky Collection

Five hundred years of Jewish manuscript and printed book illumination are presented in Highlights from the Braginsky Collection scheduled to open at Yeshiva University Museum on March 17, 2010.

This breathtaking exhibition, excellent catalogue and innovative website (braginskycollection.com) demonstrate concretely that Jewish visual artistic creation continued to flourish in Europe (and elsewhere) from the 15th century (marking the cessation of illuminated Spanish Haggadah production) until the advent of the Enlightenment that ushered in the birth of modern Jewish visual culture in the 19th century. It reveals the vibrancy and creativity of Jewish cultural life all too frequently overlooked and ignored. Perhaps most significantly this exhibition documents how central visual creativity was to various European Jewish communities.

Rene and Suzanne Braginsky have spent the last 30 years collecting illuminated manuscripts, printed books, ketubot and megillot to create a unique concentration of artworks that defines the visual culture of the Jewish people in a very special manner. This selection of 108 objects from their collection under the sensitive curatorial direction of Sharon Liberman Mintz (Curator of Jewish Art, JTS) and Emile Schrijver (Curator, Biblioteca Rosenthaliana, Amsterdam) uncovers at least three trends of the Jewish artistic production that span five centuries. First of all is the comfort level of Jews with the surrounding European culture, secondly the high level of technical, intellectual and aesthetic production and finally the proactive role of women in Jewish communal life. Well beyond simply affirming a history of cultural achievement, this exhibition actively encourages the production of Jewish art today, giving invaluable credence to the notion that Jewish art has a deep and fertile history throughout the long and tragic European Diaspora. As vibrant creators of a visual and literary culture, Jews, who lost their homeland and were barely tolerated in the lands of their exile, have resolutely refused to lose their identity and commitment to visual creativity.

One significant strength of the Braginsky Collection is its holdings in the 17th and 18th century school of manuscript decoration of central and northern Europe. The exhibition section “Manuscripts and Printed Books” contains no less than 30 illuminated texts and, while many are anonymous, we can still identify the work of 10 known artist-scribes. These artists frequently produced multiple works: Moses Judah Leib ben Wolf Broda of Trebitsch, 1723 (7 manuscripts), Aaron ben Benjamin Wolf Herlingen of Gewitsch, 1725 (over 40 manuscripts), Nathan ben Simson of Mezeritsh, 1730 (25 manuscripts), Joseph ben David of Liipnik, 1739 (16 manuscripts), Uri Fayvish ben Isaac Segal,1750 (12 manuscripts), Barukh ben Shemaria, 1795, Hijman Binger, 1796, Charlotte van Rothschild, 1842, Victor Bouton, ca 1860; to name only the artists and their works who are known to us now. Clearly, considering the ravages of European history and the Holocaust, these are but a few of many heroic but uncelebrated Jewish artists.

The diversity and creativity of these works are awesome. The Harrison Miscellany, ca. 1720, is unique for its 60 full page anonymous illuminations from Genesis that face Hebrew prayers, poems and sayings most likely originating in the Jewish community of Corfu, Greece. While the artist was probably not Jewish the production of this luxury volume by an individual in the Corfu community indicates a deep affiliation with European visual culture.

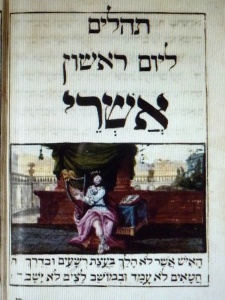

Tehillim, 1723, inscribed and illuminated by “one of the most accomplished 18th century scribe-artists,” Moses Judah Leib ben Wolf Broda, is a gem of delicacy. The page for the first day, “Ashrei,” depicts David seated on a palatial terrace playing his harp while gazing at what may be his own psalms to guide his music. The image is simultaneously dramatic in its contrasts and rich colors and contemplative as it explores the relationship between music, the inspired artist and sacred text.

No less innovative is the Herlingen Haggadah, 1725, by Aaron Wolf Herlingen of Gewitsch which features 60 painted illustrations. Since the title page shows not only Moses and Aaron but also Miriam featured prominently with her life-giving well, Emile Schrijver in the catalogue speculates that this masterpiece was created for a woman named Miriam. Additionally the depiction of the 12 different stages of the Seder features a scene repeated with small changes has a feminist bent. We see a set table, framed with heavy drapery, at which four contemporary individuals, three men and one woman, are seated. On the left is an older man, perhaps a guest, seated next to a young man. Next is a poised woman seated next to an adult, probably her husband. What is noticeable is how much she is involved in each action, holding her own wine cup at Kiddush and benching, washing along with all the others, actively gesturing as a full participant in all aspects of the Seder. Later in the illuminations another woman is prominently seen next to Moses as he leads the people out of Egypt. There is certainly a woman’s touch here. Another illuminated work that may be by the same artist-scribe Herlingen is a Birkat ha-Mazon that includes other blessings, including Shalosh Mitzvot Nashim, specifically women’s blessings, indicating that it was intended as a gift for an obviously literate woman.

Perhaps the most startling work in this section is the Charlotte von Rothschild Haggadah, 1842. It features ten sophisticated full page and eight smaller text illustrations, producing the “only Hebrew manuscript known to have been illuminated by a woman.” The work is probably based on preparatory sketches by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim and is therefore highly finished and conservative in style. Nonetheless for Charlotte von Rothschild to have acquired the technical skill and aesthetic sensibility to produce such a finished work is especially remarkable. It is clear that she utilized not only the finest artistic ideas of her time but also relied on a working knowledge of 18th century Jewish illuminated manuscripts.

One thing that makes this exhibition even more remarkable is that while in person only one page of manuscript is visible, the website, braginskycollection.com, allows one to electronically peruse multiple pages of each illuminated manuscript, zooming in on details at will. It is noteworthy also that each artwork is accompanied with a clear and scholarly introduction, effectively opening up the images to a deeper understanding and appreciation. The erudite catalogue contributions of Elka Deitsch, Gabriel M. Goldstein, Sharon Liberman Mintz, Shalom Sabar, Menahem Schmelzer and Emile G.L. Schrijver have been invaluable in preparation of this review.

The exhibition continues with an entire section devoted to 22 ketubot, all of which are by anonymous artists dating from 1648 to 1905. The styles are diverse and intensely creative, freely combining local decorative elements with illustrations of biblical allusions, midrashic scenes and poetry. The majority seen here are from Italy where the figurative elements of the Baroque are keenly felt. One from a Sephardic family in Livorno, 1748, is framed with an elaborate intertwined pattern, known as a “love knot,” crowned by a floral decoration that is dominated by two multicolored birds, a symbol of the loving couple. Also included are ketubot from Sephardic communities in Amsterdam, Bayonne, France, and Gibraltar.

The Megillah Esther, the final exhibition category, is unique among sacred scrolls in that it does not contain the name of God, thereby rabbinic authority has frequently allowed it to be decorated and used in the ritual reading on Purim. The 17th and 18th centuries were a Golden Age in which Jewish artists produced many such scrolls. Shalom Italia (1618–1664?) was instrumental in popularizing printed border decorations that included illustrations from the textual narrative. Engraved borders allowed for hand coloring, individual additions and ultimately streamlined production of a elegant yet economic ritual object. Parallel to this technique was the continuation of hand made illuminations, such as one finely drawn megillah in sepia ink from Amsterdam, 1675, featuring 38 elaborately detailed scenes. In another megillah with an elaborate printed border from Amsterdam, 1701,

is the extensive creative use of midrashic material; an example is Vashti being executed by strangulation by two women, her rebellion seen as threatening the stability of marital harmony. Jewish artistic creativity knew no technical bounds, only the exultation of their inspiration.

One Esther scroll dated around 1740 in Vienna excels in pen and ink illuminations combining fine tracery of foliage and bird and animal motifs with striking Turkish costumed narrative figures and scenes. The beauty and intricacy of this scroll is indicative of the production of these luxury ritual objects for “wealthy Court Jews who acted as financial agent for ruling members of the Hapsburg Empire.”

Finally at the New York venue of this exhibition (Yeshiva University Museum, NY until July 11, 2010, preceded by Bibliotheca Rosenthaliana, Amsterdam and followed by Israel Museum, Dec 2010–April 2011) four additional manuscripts will be shown, one of which makes history. It is the Estellina Megillah, Venice 1564, the earliest known complete decorated Esther scroll (sold at Sotheby’s in December 2009). By the standards of this exhibition it is a modest work of art, decorated with female caryatids along with male and female satyrs that form columns dividing the text and decorative arches connecting them, quite the norm for Renaissance book illumination, bearing little relation to the Esther text. What is extraordinary is the colophon or signature panel that states that this megillah was completed on Tuesday, 3 Adar, 5324 in Venice and was written by Estallina, daughter of the Katzin Menahem, son of the Rosh Katzin Jekutiel. She was a member of a prominent Venetian family, clearly literate and skilled enough to write a megillah herself. Rabbinic opinion is divided as to whether a woman may write a kosher megillah. Those permitting it reason that since women are obligated in hearing it, they are eligible to write it. Whatever the case, this megillah is extraordinary evidence of women’s engagement in the material and spiritual aspects of Jewish communal life over 400 years ago.

Go and enjoy the riches of the Jewish visual heritage seen in Highlights from the Braginsky Collection at the Yeshiva University Museum. European Jews, oppressed with forced badges, restrictive ghettos, periodic burnings of the Talmud, fanatical messianic movements, the murderous rampages of Chmielnitsky and their own inherent differences, managed to create a vibrant visual culture over 300 years long. We should be proud and inspired. And we’ve got a lot of creative work to do if we are ever to catch up with our brave and artistic ancestors.

The Braginsky Collection: A Journey through Jewish Worlds

Hebrew Manuscripts and Printed Books

Yeshiva University Museum – Center for Jewish History

15 West 16th Street, New York, N.Y.

www.yumuseum.org