The Art of Matrimony

Ketubot are the magical crystal ball into the life, concerns and joys of the Jewish community. Perhaps no other Jewish artifact is so openly expressive of the dreams, desires and fears of the everyday world of Jewish life throughout the ages. To illuminate this fact Sharon Liberman Mintz has expertly curated The Art of Matrimony: 32 Marriage Contracts from the Jewish Theological Seminary currently shown at the Jewish Museum.

“The ketubbah, perhaps more than any other document, reflects the peripatetic history of the Jewish people and the tendency of Jewish art to bear the imprimatur of the time and place in which it was created.” (Dr. Alfred Gottschalk, forward to Ketubbah (1990) by Shalom Sabar.) This perspective is evidenced first of all by the broad geographical scope of the 32 works chosen from the 600 ketubot in the JTS collection. We see works from Egypt, Italy, Croatia, Greece, France, Netherlands, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Afghanistan, India, Jerusalem, Syria, Morocco, Turkey, Ukraine, New York, Brooklyn and New Jersey. The matching diversity of decorative motifs and expressions will be apparent as we sample some of these visual joys.

The ketubbah, chiefly a Talmudic document, is a contractual guarantee. It documents a marriage and primarily stipulates guarantees made by the husband to: 1) Support his bride “according with the practice of Jewish husbands…” 2) Provide funds that will provide for his bride upon his death or their divorce, and 3) Provide a gift that will match his bride’s dowry at his death or their divorce. The ketubbah is the wife’s property and must be kept in her possession to allow marital relations. If lost or destroyed, it must be replaced. In short, it is Judaism’s writ of protection for a wife. But why did it also become a traditionally decorated document?

Scholar Shalom Sabar (who is completing on the definitive catalogue of the JTS Ketubbah collection) maintains that this custom originated among the Sephardim following the Spanish exile and was enthusiastically emulated by the Italians, initially by the Venetians in the 17th century. It was the public reading of the beautifully decorated ketubbah under the chuppah that encouraged wide-spread decoration to add to the celebratory atmosphere. Curator Sharon Mintz adds that it also inhibited fraud since if the document utilized a decorated border it would be difficult or impossible to add anything that was not originally agreed upon. And of course the elaborate decorations that soon blossomed in Italy and beyond became a central part of hiddur mitzvah, the beautification the mitzvah of the ketubbah itself.

The 17th and 18th centuries were the golden age of Italian ketubbah production for most of Europe, utilizing the ubiquitous decorative style of the Baroque and Rococo imbedded with extensive Judaic symbols and text. Unfortunately with the Emancipation of many European Jews in the early 19th century and their resulting secularization, the illuminated ketubbah went into rapid decline, practically disappearing both in Europe and America by the Second World War. Paradoxically, only with the interest in a revised and modernized text among Reform and Conservative Jews in the 1960s did the illuminated ketubbah begin to make a comeback in popularity among many Jews. Still the custom of illuminated ketubot has yet to take hold among the Orthodox today.

The Italian ketubot are extremely rich in expressing multiple layers of meaning. Over the years most major centers of Italian Jewish communities developed their own unique style and symbols in ketubbah decoration. The 1749 ketubbah from Venice is typical. While the elaborate floral border is embedded with the signs of the Zodiac, the four corners directly adjacent to the text panel depict the menorah, the laver, the showbread table and Aaron and the cohanim, almost certainly expressing traditional messianic yearnings. An intricate and endless “love-knot” dominates the upper register while the text below is divided into the ketubbah itself on the right and the tena’im (pre-marital conditions such as dowry, other financial conditions, penalty for default, etc.) on the left. All in all this impressive illuminated manuscript expresses manifold aspirations, practically a declaration of faith and plan for the new couple’s life together. So much so that the tena’im states the couple “agree to conduct their mutual life with love and affection, without hiding or concealing anything from each other; furthermore, they will control their possessions equally. However, in case of a quarrel, God forbid, between them, they shall follow the customs of the Ashkenazim in Venice in this matter.” The complexities of a “mixed marriage” clearly had to be planned in advance.

The ketubbah of 1725 from Corfu, Greece (under Venetian rule 1387-1797) exhibits a totally different design from its Venetian cousin. It is literally teeming with figurative details. Aside from the normative Zodiac that frames the single text panel, there are no less than 26 figures depicted including angels, cherubs, satyrs, and biblical figures, not to mention birds and other ornamental creatures. At the bottom the Akeidah is depicted on the left while on the right we see the Children of Israel are collecting the Manna. While not clear in this document, normally biblical narratives reflect the names of the bride and groom. Corfu was a major non-Italian center of ketubbah production and it is highly likely that the scribe who wrote the ketubbah was also the artist that executed the ink and watercolor decorations. This fact illustrates the rare confluence of the artistic and pietistic in a Jewish document.

In stark contrast is the Mantua ketubbah from 1689. Here there are also many biblical illustrations shown, a total of 27 in all. We begin with Adam and Eve, the first wedded couple, beneath the Tree of Knowledge. What follows is an eye-opening parade of biblical narratives that map the tangled male-female relationships in the Bible: Lot and his daughters, Joseph and Potiphar’s wife, David and Bathsheba and Susanna and the Elders among many other stories of male-female conflict. It is almost as if the illuminator (almost certainly a non-Jew) wanted to warn the newlyweds of the potential difficulties ahead.

In yet another image deeply influenced by Italian models, the Rome 1836 ketubbah exhibits a neo-classical 19th century sensibility. The clean, simple design that echoes a hanging pendant has condensed the symbolic elements to a two roundels top and bottom and a cartouche on either side of the text panel. While the meaning of the two birds, one male and one female in the upper roundel is possibly a simply poetic allusion to romantic love and fidelity, the lower roundel of a duckling is unclear. On the other hand the cartouches are a clear insertion of secular Italian images expressing the involvement of Italian Jews in contemporary national issues. On the right the female figure representing Victory is seen with the classic attributes of an olive branch and a crown. Verses from Psalms 37:11 and Proverbs 4:9 secure this reading. On the other side the image of Hope with an anchor is likewise presented. These symbols echo the preoccupations of both Jews and non-Jews over the status of Rome after the Napoleonic wars, at that time tightly ruled by the Vatican, in relation to the emergence of a unified Italian kingdom that was only finally achieved with Rome as its capital in 1871.

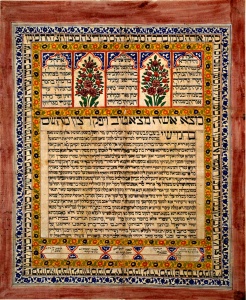

In another expression of fidelity to national culture, the 1885 Isfahan, Iran ketubbah is unashamed to proclaim its allegiances. It is, of course, a world away in design from its Roman relative, typical of its Islamic culture in never using figurative elements. Created by a well-known Isfahani ketubbah artist, Moses ben Yeshu’ah (or under his direction), it is a simple folk masterpiece. Bright colors and simple forms predominate with the text clearly subordinate to an exuberant design of text, flowers, birds, and two rampant lions with a happy-faced sun rising behind them. What at first seems pure joy is quickly understood as deep nationalism when we realize that the ancient symbol of Iran is the lion with the sun. For these Jews on their wedding day one very important thing to express was their love of their homeland, Iran.

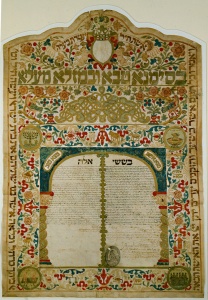

Manifestations of home, i.e. that which forms individual identity, are central to any visual expression of the ketubbah, which is the legal contract to create a Jewish home. The 1867 Herat, Afghanistan ketubbah takes this notion literally. Interestingly, this may be the most visually integrated ketubbah we have looked at since the proportions of text to decorations are almost equal. Echoing the “carpet page” illuminations of early decorated Torah manuscripts, one could imagine this as a rug design in its uniform emphasis on careful calligraphy alongside rhythmical floral designs. Contrasting blue borders with cool earth reds and ochres allows the black of the text to operate simply as another abstract design element. The repeated architectonic patterns of contrasting colors and rhythms along with the five Islamic-style arches that frame text and two images of blossoming flowers create a two-dimensional manifestation of an actual affluent home in Afghanistan.

We have looked at only six examples of widely different ketubot among the 32 offered at The Art of Matrimony. The rest and the wall texts (from which the majority of my observations are based) are equally revealing, opening up the dizzying richness in Jewish life and practice across a mere 300 years of Jewish diaspora. Isn’t it interesting that this feast of Jewish life is found in the rarified convergence between rabbinic supervision of the institution of marriage and the irrepressible desire of the Jewish people to artistically decorate a holy contract between man and woman? What greater Hiddur Mitzvah could there be?

The Art of Matrimony

The Jewish Museum

1109 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.

www.thejewishmuseum.org