The Art of Eli Frucht

How and why does a person become an artist? The ways and means are many and yet each person finds their own unique path; sometimes straight and clear, other times complex and surprising. Eli Frucht’s blossoming as an artist in his middle age is simultaneously unexpected and yet curiously predictable.

Eli Frucht last appeared in [the Jewish Press’s] pages on February 8, 2002 in my review of his collection of Jewish Art. As an observant businessman in real estate he had been buying contemporary Jewish art for at least 15 years and had amassed a fine private collection of mostly realist genre works focusing on observant communities here and in Jerusalem. What impressed me at that time was the intense connection he had with both the subjects and artists he collected. Each place depicted was one he was intimately familiar with, either as a glimpse from his past or a familiar contemporary scene from his Brooklyn and Israeli experiences. Additionally each artist was for him a living, breathing personality that he had gotten to know rather well. Some of the artists have actually become his friends.

This collector’s immersion into the rarified world of artistic visual experience and those who create it had rather surprising consequences for his own life. Starting with only a few lessons from professional artists, Frucht underwent a slow transformation from an appreciator of art to a creator. And while he cites a number of important artistic influences, Simon Gaon and Itshak Holtz to name only two, the truth of the matter is that Frucht has forged a clear and independent style in a handful years to become an original and highly competent self-taught artist. His work over the past four years is characterized by a strong sense of composition, a love of light and color as well as a passion for the pure physical pleasure of paint itself.

Frucht’s art has an impressive range, spanning landscape, cityscape, interiors and portraits. He has produced many paintings of his Seagate and Boro Park, Brooklyn neighborhoods, choosing to create virtual portraits of eye-catching buildings. It is of course his paintings with overtly Jewish themes that deeply fascinate me.

Typical of his eclectic vision is Bakery. Ostensibly, it is a simple depiction of a bakery display case chock full of cakes. And yet the very singular way the young man lines up with the end of the case alerts us to a more complex scenario. His figure links the foreground display case with the golden-lit cases behind him in the center-top of the composition. Clearly this must be a Jewish bakery evidenced by our young Jew with beard and yarmulke and the pictorial connection with the sweet, tasty desserts. When the artist informed me that this bakery “portrait” actually depicted special dairy cakes and cheesecakes for Shavuos, I immediately saw the deeper story. In this perspective, this is genre painting at its best.

One skill that is not on the course list of most art schools is the psychological sensitivity that Frucht seems to understand naturally. Jerusalem Staircase with Boy explores the dramatic tension between the ascending stairs that then split in opposite directions. A young child is seemingly riveted at its base. His innocence is overwhelming with the towering staircase only hinting at a future of momentous choice and growth. The added personal observation by the artist that under the arch on the right side is the site of his childhood home, only heightens the quiet unfolding drama, just slightly off balance to increase the psychological tension.

Underlying many of these remarkable works is Frucht’s passion to paint expressions of yiddishkeit from the inside of the religious community as a veritable force of nature. But this is yiddishkeit deeply transformed by an artist’s perspective, expressed in the uniquely artistic language of paint, color and light.

Synagogue interiors with congregants are in fact relatively rare in pious Jewish art. It is almost as if the actual act of prayer was too private to depict. Nonetheless, Frucht’s Shomrei Shabbos Interior manages to find a unique compromise. This famous storefront shul in Boro Park is known for its round-the-clock minyanim. His vision is similarly unique. As we make out the massive Aron HaKodesh, a man is about to start to lead the prayers. His simple, almost abstract depiction contrasts with the two figures on the left seated at tables. One seems to be reading a newspaper while another just stares towards us. Daylight streams in from the windows even as a mysterious dark skylight hovers over the main space. And yet in spite of all this visual complexity it is the Aron HaKodesh that dominates. Not only its rich ornamentation but the paroches with the brilliant embroidered golden menorah overwhelmingly dominates the scene. And therein lies the visual conundrum. The seven-branched menorah is so highly contrasted with the black velvet paroches that it seems to gain an independent three-dimensional identity, amazingly standing in for an actual menorah, alluding of course to the menorah in the Second Temple. This unexpected element suddenly transforms the local minyan mill into a gateway to the Holy of Holies, which of course it is.

Frucht finds wonder in every expression of Jewish observance. Artist in the Succah is a diminutive testament to homespun creativity. He depicts a local neighbor who is known for creating his own succah decorations year in and year out. We see him as he sits amidst his colorful creations punctuated by six rectangular plaques high up in the picture, representing the Ushpizin. Traditionally we welcome seven Ushpizin: Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Moses, Aaron, Joseph and David. But in Frucht’s painting only six plaques are in the ordered place of honor. And so Frucht tells us that the subject of the painting, his Viznitzer chasid friend, is Abraham himself!

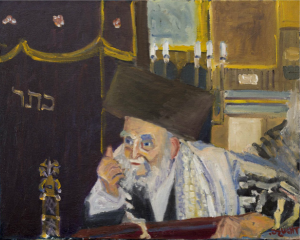

Portraits of special friends are a kind of specialty for Frucht. A really special portrait of the venerable Rabbi Elimelech Ashkenazi is a case in point. The rabbi is enthusiastically explaining an especially important point, leaning forward and gesturing with his thumb. An ornate tallis is still draped over his shoulders and his rich fur shtreimel frames his head and white beard. His face radiates intense joy that reflects the subject of his discourse, the once in 28 year Birkas haChama. Just as God blesses and illuminates us with his sun, sustaining his creation; so too a Torah sage nourishes the Jewish people.

On a more mundane level the artist’s depiction of Artist in his Studio touches a similarly personal note. The studio is crowded with paintings, some on easels and others lining the walls or leaning against one another. Humbly sitting in the lower left corner is the artist Itshak Holtz, master of his realm, gazing out at the viewer. And in a very important way, this is exactly what an artist and his artworks actually do. They gaze out and hope to engage the viewer in the art. By their color, light and intensity they invite us into their uniquely created little world. Everyone knows their world is but an illusion, a fiction of paint and canvas. But the hope is that the viewer will ponder what he or she sees and by these artistic means, reflect on the very real and wonderful world around us.

That world for Eli Frucht is the universe of yiddishkeit—Jewish life lived according to Torah and deeply cherished tradition. In the ultimate sense that is why he, only a few short years ago, was practically forced to become an artist. His sensitivity to yiddishkeit hand in hand with the visual expressions he had collected for years drove him to bring his own vision to Jewish art. By working hard and teaching himself how to make images of the things that he loved and felt passionate about, Eli Frucht has opened up his world of yiddishkeit for us in unexpected ways. In light of his images we can never look at a bakery, a shul, a succah or a Torah sage in quite the same way. Frucht’s sensitive and unique images transform the things we thought we knew well. It is his gift to us.

The artist may be contacted at [email protected]