Singer’s Artists

The illustrator stands in an oft-denigrated position, scorned by modernists and traditional purists alike. For both schools of thought the sublime of art cannot be rendered literal. On the other hand, illustrators are curiously accepted if not celebrated by those in a postmodern disposition.

In the last twenty years or so a creative relationship to text, narrative or non-visual motifs has gained legitimacy if not primacy in the visual arts. Under the watchful guidance of director Jean Bloch Rosensaft and the curatorial skill of Laura Kruger the Hebrew Union College Museum casts one of its current exhibitions into this ideational fray. Isaac Bashevis Singer and his Artists is in its curious way an exposition on the illustrational as a contemporary motif.

Isaac Bashevis Singer was a notoriously prodigious writer, turning out countless stories, essays and a daunting 86 books, of which 32 were illustrated by the 17 diverse artists brought together here for the first time ever. Curator Laura Kruger has assembled a remarkable collection of artists, notable for not only their fidelity to Singer’s texts (to be expected of any illustrator) but the incredible diversity of creative visions. In a rather remarkable way each artist relates to Singer in a uniquely personal manner, finding a thread of individual connection to the Yiddish master that make their illustrations not only serve Singer’s text but also allow for enormous personal expression.

For many American Jews Singer was a kind of universal Jew, deeply rooted in the “Old Country” and yet thoroughly familiar with the immigrant and post-Holocaust experiences of millions of New York co-religionists. It’s clear that his life history laid the foundation for his writing. He was born in 1902 in Poland and grew up in small towns Leoncin and Radzymin, finally moving to Krochmalna Street in Warsaw. His father was a Hasidic rabbi and his mother the daughter of the rabbi of Bilgoraj. He learned in heder and yeshiva but felt unsuited to become a rabbi and finally became a translator and journalist for several Yiddish newspapers in Warsaw. Fleeing rising anti-Semitism he immigrated to the United States in 1935 and quickly found his home as a journalist and critic for the Forverts (The Jewish Daily Forward) where he worked throughout his life. All of his works were written in Yiddish, many have been widely translated and in 1978 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature.

Among the more than 150 original illustrations shown here many are, not surprisingly, for his children’s books. While the vast majority of his work was for adults, Singer once quipped that he also wrote for young people because “they still believe in God, the family, angels, devils, witches, goblins and other such obsolete stuff.” It is clear that the artists assembled here are believers too.

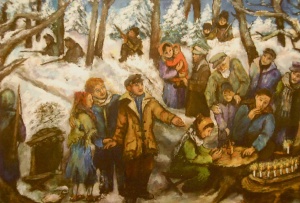

Irene Lieblich (1923-2008) was a survivor who took up painting at the age of 48 and, through an exhibition of her work, became friends with Singer after which she illustrated two of his books, A Tale of Three Wishes (1976) and The Power of Light: Eight Stories for Hanukkah (1980). All her 13 illustrations shown exhibit a folk-art charm that reflects both Singer’s and her roots in Eastern European pictorial traditions. Three shtetl children witnessing an angel driving a chariot through the sky before a chorus of angels can be summoned by her as easily as a young boy and girl emerging from a manhole in war-torn Warsaw. Her Partisans in the Forest is especially affecting. In a wintery scene a group of Jews huddle around a makeshift menorah while two play with a dreidel on a tree stump, surrounded by armed partisans anxiously guarding the evening ceremony. The simple composition slowly reveals first courageous piety, then childish playfulness and finally the deadly seriousness of their guards. Jewish faith at work.

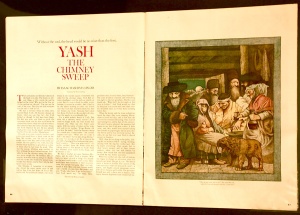

Maurice Sendak (1928-) is perhaps the most famous illustrator in the exhibition, notably for Where the Wilds Things Are (1963), and his collaboration with Tony Kushner in recreating the children’s book and Holocaust opera, Brundibar (reviewed here May, 2005). Yash: The Chimney Sweep is typical of much of Sendak’s work; featuring a densely realistic illustration of a crowded room filled with disgruntled and puzzled shtetl types surrounding a man with his finger pointing to his bandaged head. Of course the illustration doesn’t make much sense until you read the story, continently available at the exhibition. It seems that Yash was a non-Jewish chimney sweep who fell off a roof, banged his head and then could suddenly read everybody’s minds. Suddenly there were no secrets. Life changed; nobody could safely lie, thieves were out of business and lost children and horses were easily found. Just imagine how upsetting life would quickly become. That’s why Sendak’s illustration is so on the mark. Everybody is distressed, sour and angry. Except for Yash’s mother who has been charging a kopeck per visitor and the hapless Yash giggling at his newfound powers.

The roster of artists who illustrated Singer’s books is extremely diverse. Some shared his Jewish Eastern European background and most are professional illustrators. Yet among these are well-known artists in their own right: Roman Vishniac (1897-1990), noted documentary photographer of Eastern European Jews in A Vanished World (1947) became friends with Singer and permitted the use of his works in Singer’s A Day of Pleasure: Stories of a Boy Growing Up in Warsaw (1969). Raphael Soyer (1899-1987) was a close friend known internationally as an American Social Realist painter from 1930 – 1950. His illustrations here of flying demons, nudes and fantastic figures are especially revealing exceptions to his normally dour painting style. Another international artist, Larry Rivers, illustrated a deluxe edition of Singer’s The Magician of Lublin with a signature drawing of a contemporary man donning tefillin; simple, modern and disarmingly convincing.

Among the illustrators Antonio Frasconi (1919-) is particularly noted for his images in Yentl the Yeshiva Boy (1983). Working in his famous woodcut style the image of two yeshiva ‘boys’ standing arm in arm is particularly disarming (pardon the pun). It is of course the radical content of Singer’s story of a rabbi’s daughter who dresses as a boy in order to study in yeshiva that makes this image so transgressive in its innocence. And of course that aptly sums up Singer’s approach too.

In many ways Ira Moskowitz (1912-2001) epitomizes Singer’s illustrators. He was a close friend and confidant who was deeply in synch with Singer’s worldview. A fellow Polish Jew who arrived in New York a few years earlier than Singer and, after traveling and working in Taos, New Mexico, returned to New York to become close friends with Singer. Moskowitz illustrated several of Singer’s books and created portfolios inspired by individual personalities Singer had created. He is represented here by many drawings, watercolors and paintings, perhaps most beautifully by Dance with Kerchief from Satan in Goray (1981). The Hasidic couple dancing exhibits a genuine sensuality that overcomes its stereotypical subject matter even though both figures seem to be simply striking a pose for the artist. This is creates an especially sharp tension with the subject of Satan in Goray: the tragic years of the Chmielnicki massacres in Poland and the false hope of Sabbatai Zevi. Simple Jews danced, demons lurked and a village girl becomes possessed by a dybbuk until she is saved by a Torah-true Jew. Set in this context Moskowitz’s image takes on much more complex meanings. The old couple symbolizes faith, sensuality and ecstasy swept along the winds of change.

Isaac Bashevis Singer and his Artists similarly sweeps us up in the creativity and passion of the master Yiddish writer’s texts. Curator Laura Kruger is careful to always provide the textual references, either summaries or the short stories themselves, so that the images live and breathe within the very texts they emanate from. Once joined together they nurture and complement each other like an old married couple; one starts a sentence and the other finishes it. By doing so she insists that at least in this framework, text and image are inseparable and that like all good commentary next to its source, make both even more a joy to behold.

Hebrew Union Collage Museum

One West 4th Street, New York, NY

www.huc.edu/museums/ny