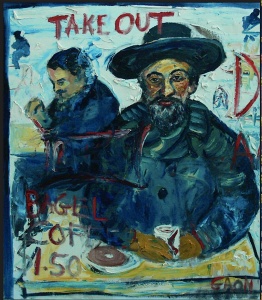

Simon Gaon’s Jewish Paintings

Bagel Take Out, a rather large (54” X 50”), oil painting by Simon Gaon, confronts the viewer with a typically challenging New York sidewalk vista. As is usual in our tumultuous city, people, food and signage are constantly being thrust into our field of vision, loudly completing for attention and patronage. It is exactly this breathless experience that Simon Gaon thrives on and has effortlessly captured in literally hundreds of paintings over his 50 year artistic career, spent mostly in our fair town. A recent late afternoon visit to his Upper West Side apartment/studio revealed not only the vast scope of this master Expressionist painter, but also a small cache of his overtly Jewish-themed works.

As I described Gaon in my review in June, 2001 (“In Search of Ancestors, Sculpture by Simon Gaon” at Yeshiva University Museum), his Bukharan Jewish roots are deeply embedded on both sides of his family, echoed in his early yeshiva education. And yet the lure of the art world was irresistible; first attendance at the venerable Art Students’ League on West 57th Street and then the prestigious McDowell Traveling Scholarship opened the doors of the European art capitals for years of study, travel and work until the early 1970s when he settled down (if you can call it that) in his New York home. Formally supporting himself with landscapes, cityscapes and flower paintings, his subject matter matured into what might be called essentialist New York Street Painting; so much so that he helped found an artist’s group called “The Street Painters” in 1978. Passionate works reflecting the ceaseless flow of drama and tragedy leapt off his street-based easel as Gaon set his artistic sights on Times Square, subways, the waterfront and nightscapes as well as the kind of storefront views like Bagel Take Out.

There is an inherent ephemerality in the two figures depicted that reflects the transitory nature of take out restaurants. Everything, including that which is consumed in the store, is “on the go.” These men, barely caught in the thick paint that depicts the harsh florescent light, are only pausing for scant nourishment in a larger journey implied by their buttoned up street clothes. The “take out” is them.

Sukkoth has understandably (and paradoxically) a totally different feel. Here the family, wife, husband (dressed in an echo of Bukharan costume), 2 children and a mother-in-law (perhaps) feel quite at home in the lush green environment of the thickly decorated succah. Gaon divides the painting horizontally to emphasize the equal importance of the seated individuals performing the mitzvah with the lush environment of the succah itself. His concern with the halachic nature of the event is so much so that he bends the perspective to show the blue sky peeking through the s’chach above their heads, demonstrating that it is indeed a kosher succah.

Simon Gaon proudly affirms his association with a wide range of Expressionist artists from Van Gogh, Derain, Vlaminck, Corinth, Kokoschka, as well as his teacher Arthur Bressler. Portrait of a Lubavitch Hasid acknowledges Soutine’s influence. The slight figure, off center and engulfed by blue vehement brushwork seems to imply a man engulfed by techeles, the holy blue dye, and the awesome reflection of Heaven’s majesty. Gaon’s feverish brushstrokes, especially in the face and barely recognizable hands, easily confirms this meaning.

A narrative shift is what immediately interests us in Gaon’s Akeidah. Finding in Gaon’s paintings substantive Jewish subject matter is a noteworthy anomaly since most artists who devote themselves to scenes of everyday life do not venture into Biblical narrative. Gaon’s Akeidah clearly changes the artistic discourse.

Abraham dominates the left side of the painting in a red robe, holding down the head of Isaac, seen in profile, as the curved knife is poised at his throat. On the right a ghostly apparition has reached out to touch the far side of Abraham’s beard. The gesture is shockingly gentle, almost a loving caress, that nonetheless causes our forefather to hesitate in the midst of his terrible deed. The curve of the angelic arm that saves echoes the curve of the knife that would destroy. Gaon has caught the crucial moment with warm greens and reds in contrast to cool blues and grays, making paint and its color temperature carry the narrative between the human and the divine.

Moses Throwing Down the Tablets internalizes Moses’ dramatic anger at Jewish rebellion. Below on the left the Golden Calf blazes and hundreds of diminutive figures mill around while Moses turns away from the melee below. His black and white stripped tunic sets him apart just as his ruddy skin color makes him seem especially down-to-earth. We know he has just spent 40 days and 40 nights on the mountain with God. Just as his arms are raised holding the unseen Tablets of the Law and his eyes are closed, we are drawn into his similarly hidden mental state. We can only speculate what must be going through his mind as he considers the desecration of God’s holy gift by the ungrateful populace below. This painting brings us to the edge of Moses’ consciousness.

The next two paintings remove any doubt as to the emotions involved in Abraham Smashing the Idols. There is a steely determination on the part of Abraham holding the cudgel like a baseball bat, ready to smash the head of the grotesque little white gnome seated next to him. The odd assortment of figurines; masks, a white little goat and a greenish blue creature, all summon the mythological universe that surrounded Abraham and seemed to challenge the One True God.

Gaon’s second painting of the same subject considers the threat of idolatry as more catastrophic. Here the idolatrous world encompasses the whole painting, painted in greys and blacks, and even spreads to the clothing and headdress of Abraham himself. Only his face and arm are depicted in warm yellows and reds, still preserved from the dread infection. In this painting Abraham is almost overwhelmed by the pervasive plague he swats. The disheartening struggle with idolatry seems enormously important for Simon Gaon even though the subject is not found in Tanach at all and only surfaces in the Midrash Rabbah.

586 BCE (Jeremiah Saving the Torah) presents a similarly sobering perspective. The hounded and persecuted prophet, just released from King Zedekiah’s prison, is pensively holding a Torah scroll, presumably rescuing it from the burning Jerusalem behind him. The brilliance and passion of the painting reflects the extraordinary moment Gaon has depicted. This is the exact beginning of the first Diaspora. The intense swirling blues of the sky are also found in the scroll, reflecting the divine creed that we must take with us from the midst of each communal disaster. Someone had the terrible job to tell the Jewish people the punishment that awaited them. Someone had to carry those prophecies and the Torah’s truths out of the ashes. That crushing burden fell to the simple perplexed man, Jeremiah, we see here.

By the very nature of his feverish execution Simon Gaon’s work has the edge of reality; since the highly impastoed painted surface seems “alive,” so too that which is depicted seems “alive.” In all his other paintings the passion of the moment elevates the seemingly mundane into an extraordinary event. Here, when joined with the gravity of the Biblical Narrative, Gaon’s work evidences an exemplary intelligence and insight that suddenly opens up the narrative in a totally unexpected and refreshing vision. Whereas it is the life of the streets of New York that pulsates in his other paintings, here the Biblical leaps alive, demanding its very own reality. In Gaon’s Jewish paintings the life of the Jewish people becomes animated, precious and invigorated by his brushstrokes.