Memory Paintings

Shmuel the artist is what they called him back in the Old Country. At home and in cheder he was always drawing or modeling something. Born in 1882 in Wolkovisk, Russia he grew up in poverty, his father a Torah scholar and mother a peddler of grain and flour. Early on he was orphaned and with his soprano voice was apprenticed to a cantor to give performances from shtetl to shtetl in the Polesie swampy woodlands of Byelorussia.

Finally he immigrated to America in 1904 at the age of 22 to seek his fortune. Within five years in New York he decided to become a full time professional artist and did exactly that for the remaining 62 years of his life. Norman L. Kleeblatt, Curator of Fine Arts at The Jewish Museum maintains that “As a folk master, Rothbort, the untutored painter and sculptor, also had the good fortune of enjoying a considerable…reputation during his lifetime. There were, after all, only a handful of ‘naïve’ painters who achieved Rothbort’s level of recognition while alive. Indeed, he belongs in a class with his contemporaries, ‘Grandma’ Moses, John Kane and Morris Hirshfield.” Quite an accomplishment for an impoverished, unschooled Jew fending for himself in the New World a hundred years ago.

He struggled and did whatever it took to eke out a living and continue to make art. He tried dairy farming near Monticello, New York and a stint as a chicken farmer in Uniondale, Long Island but always returned to Brooklyn where he finally made his home. He painted portraits, friends and family, self-portraits, still lifes and interiors of his home. His prolific output of landscapes and cityscapes included Central Park, Brooklyn Botanical Garden, Ebbets Field, Van Cortlandt Park, Sheepshead Bay, Mill Basin, Manhattan skyline, Times Square, Lincoln Square, the Lower East Side and Brighton Beach, just to name a few of hundreds of locations. When the Depression hit and the cost of art supplies was prohibitive he turned to found objects of wood and stone to craft art objects. He quickly became a self-taught master of direct carving (in which the nature of the material guides the final image) in stone and wood. His invention seemed limitless. In 1936 he began a 28 year relationship with the Barzansky Gallery on Madison Avenue, showing in group or individual shows annually. His relative success was remarkable.

In the late 1930s he began a series of works called Memory Paintings concentrating on his childhood experiences in the Old Country. Two hundred and fifteen of these works were seen in the prize winning 1960 documentary “ Memories of the Shtetl” and became the visual resource for Jerome Robbins’ play “Fiddler on the Roof.” A selection of the Memory Paintings is currently on view at the Chassidic Art Institute until December 3, 2008. They easily transcend a mere nostalgic look backwards.

Of the eighteen paintings shown, fourteen are Memory Paintings that all feature hand carved wooden frames that function as visual and textual extension of the image. Overwhelmingly the subjects acknowledge the communal kindness that alleviated the suffering and daily poverty of these Eastern European Jews.

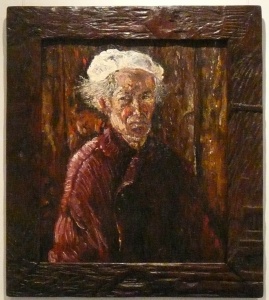

Self Portrait sets the unmistakable tone of this set of paintings. The aged artist, grey hair flying out from beneath his big white beret dramatically frames his scowling face. The expressionist treatment of his crimson coat only reflects the boiling emotions evident in every corner of the canvas and carved dark wooden frame. This fellow has not settled into a comfortable American dream.

Shavuot (1956) returns us to the inside of his family home on perhaps the sweetest holiday of the Jewish year. His mother approaches the open door with goodies for childhood guests, the very epitome of hospitality. His white bearded father stands at the family table while a chubby white cat in the foreground licks himself contentedly. All is fine in the festive home, even the ravenous guest seated on the left, stuffing food into his mouth, seems content. Still this hunger permeates the Memory Paintings.

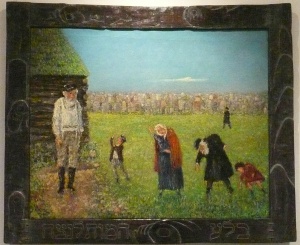

Rothbort has an insightful way with life’s inevitable events. Coming from the Cemetery remembers a terrible day long ago when an entire family mourned. A young brother and sister frame aged parents, each in one aspect of reaching down and tossing grass over their shoulder as they leave a vast cemetery that lines the horizon. One young figure lingers in the green field behind the family. Perhaps he cannot bear to leave the dead behind. And finally the old Jew, clad in black cap, talis katan and black boots, watches the spectacle from the front yard of his house. Will he be next? When will all of us, mourners and mourned, meet again he seems to ask.

The Day Eater also seems to ask a similar terrible question. Why are there so many hungry Jews? Why does hunger still rule the world? Even as the young woman graciously feeds the young man who stuffs food into his mouth, oblivious of his voracious behavior, she is concerned at his fate and conduct. This painting goes to the heart of Jewish suffering; what is the matter with communities we have created that cannot feed themselves?

The answer at first seems to be found in Leaving to America, almost certainly an image of the artist himself leaving as a youth off to the New Land. The old patriarch hands the youth, satchel in hand, a purse to prepare him for the struggle ahead. A woman weeps covering her face behind them. Rothbort has captured the classic familial dilemma that confronted Eastern European Jews for fifty years before the Holocaust.

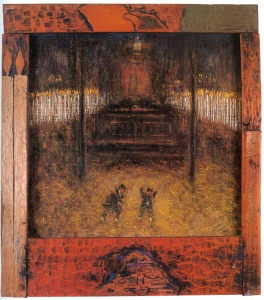

Finally we must all confront Yom Kippur. Rothbort’s image of a synagogue interior is a mysterious evocation of the holiest night of the year and surely the masterpiece of the exhibition.

As was the custom years ago men would not leave the synagogue after Kol Nidre and Maariv of Yom Kippur. Rather they would stay up all night in shul, reciting tehillim, praying and learning along with those travelers who indeed had nowhere to stay. They would be surrounded by candles that burned all night and all day to memorialize all the departed of the community. And, perhaps inevitably, they would fall asleep.

We are looking into a large darkened shul, tall columns framing a large dark bimah and further back we can barely make out the aron with a red and gold parachoes, crowned by two luchos and an eternal light. Along the wall on either side are hundreds of tall lit tapers giving off an eerie glow that allows us to see in the foreground two young men sleeping on the straw covered floor. They seem terribly vulnerable, isolated in an enormous space, and yet not afraid. The darkness punctuated by candlelight, a sonata of gold, black and red, lends a mysteriously holy atmosphere in which the lads catch a little rest. In the magical moment of painting these two bocherim represent all of us on Yom Kippur, vulnerable and yet unafraid of the holiness that surrounds us.

Samuel Rothbort had a life in art lived to the fullest. Whatever came to hand, whatever ignited his imagination and created visual pleasure was the cherished material for his creativity. Proudly he was Shmuel der Mahler.

Chassidic Art Institute

375 Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, New York