Painting and Feminism

An exhibit now on view at New York’s Jewish Museum purports to chart the course of a cultural revision—specifically, the rise of women artists, or, more specifically, the rise of Jewish women artists, or, more specifically still, the rise in the numbers of such artists exhibited at the Jewish Museum over the past 50 years. It turns out that since 1947, over 550 women artists have shown at this one venue in Manhattan. One wonders if MoMA can match those numbers.

But of course numbers don’t tell the whole story of “painting and feminism,” to cite the second half of the show’s full title, Shifting the Gaze: Painting and Feminism. Just because a woman is showing her work doesn’t mean her work is expressing a feminist agenda or perspective. Similarly, just because a woman is Jewish doesn’t mean that her work contains Jewish content (While the Jewish Museum may not necessarily think that the promotion of Jewish art is part of its mandate, the inference follows naturally from its name). Finally, just because a woman is Jewish, and an exhibited painter, doesn’t mean her art fulfills the criterion of aesthetic significance.

As it happens, the role of feminist ideology is somewhat elusive in this selection, well curated by Daniel Belasco, of over 30 paintings by some 27 artists, most of them from the museum’s own collection. Only fourteen of the works might be described as clearly feminist. One of the best paintings, Miriam Schapiro’s Fanfare (1958), is an abstraction filled with forceful gesture, expressive color and space, and creative calligraphy: hallmarks of good painting, all, but nothing that distinguishes the work as being from the hand of a woman or a man, let alone a woman or man with feminist intentions.

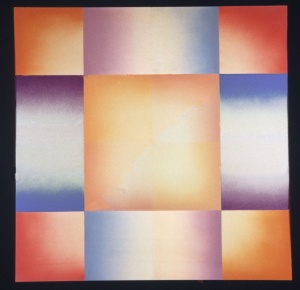

As it happens, the artworks with overt Jewish content of one sort or another are those that do “shift the gaze” most pointedly in a feminist direction. That ideological phrase alludes to the “male gaze” that feminist art theory defines as the practice of depicting women as mere objects of male sexual desire. Hannah Wilke’s Venus Pareve (1984), for instance, guides the viewer into reassessing Venus-gazing by presenting nine plaster-cast nudes, identical but for lurid color distinctions; appropriately Venus-like in their proportions, they are cut off at the thighs and arms to reveal only the prurient essentials.

It is the mechanical repetition and arbitrary unnatural coloration that “deconstructs” these nine images by ridding them of sexual appeal and rendering them pareve, the Yiddish term for “neutral” foods that according to the taxonomy of kashrut are neither milk nor meat—or, in the sexualized sense of the terms, neither female nor male. Upon closer inspection, each figure’s lower portion can also be seen to be experiencing a kind of decay, a slow disintegration of the flesh. This, by breaking down the Venus stereotype, may be intended as an additional admonition to leering Jewish males.

Similarly delving into a Jewish-feminist motif is Elaine Reichek’s Sampler: A Postcolonial Kinderhood (1993). Reichek’s medium, embroidery, is emphatically feminine, and her work, here consisting of two samplers, probes what was to her the dark essence of American Jewish child-rearing circa the 1950s. Conceived as part of a children’s bedroom, each of the two samplers bears a powerfully oppressive message. The first: “Don’t be loud. Don’t be pushy. Don’t talk with your hands.” The second: “If you think you can be a little bit Jewish, you think you can be a little bit pregnant.” The ironic meaning is that, in trying to pass as real Americans, Jews, or at least Jewish women, are pretending to have it both ways.

Other items are similarly straightforward. Victims, Holocaust (1968) is an intense work on paper, neither feminist nor painterly, by Nancy Spero: a golden Star of David affixed with six death heads, each representing a death camp, and in the center an emaciated victim vomiting.

Melissa Meyer’s painting Lilith (1992) eponymously invokes the female demon of Jewish legend, a mainstay of Jewish feminist iconography. Here Lilith is captured in a lively abstract mass of swirling reds, pinks, and violets that float upward, penetrated by a sparse but sensuous invasion of white and cream brushstrokes.

Revealingly, none of these artworks tackles the vast corpus of elemental Jewish subjects and ideas that we are heir to: Bible, commentary, legend, history, the land of Israel, and so on. Why not? About the artists in the show, the curator comments: “They painted what they knew.” And indeed, sociologically speaking, many of these Jewish artists, like their counterparts in literature, were active during the vast mid-century movement away from Jewish culture, identity, and knowledge. They defined themselves by the terms, and the fashions, of the secular non-Jewish environment, feminism prominently among them; Jewishness, let alone Judaism, was secondary at best. One can only wonder whether a younger generation of Jewish women, embracing their Jewishness at least as firmly as their role as artists, will yet precipitate a shifting of the gaze in a more truly radical direction.