The Southern Jewish Experience, Photographs by Bill Aron, Text by Vicki Reikes Fox

Imagining the tempting aroma of pecan pie and fresh challah the age-old rhythms of Southern Jewry unfold before our eyes in the seductively handsome exhibition of photographs, Shalom Y’all, currently at the Jewish Museum of Florida in Miami Beach. The show artfully fulfills the museum’s fundamental mission of presenting exhibits of Florida Jewish life, past and present. The enormous Jewish community in southern Florida (625,000; 3rd largest Jewish community in the U.S.) is home to many who originated in southern states.

The museum is housed in the stately former home of Congregation Beth Jacob, the first congregation in Miami Beach. This restored 1936 Art Deco sanctuary features a copper dome, a marble bimah and 80 stained glass windows that flood the interior with a luminous light. The permanent historical exhibition detailing Florida’s Jewish life from 1763 to the present, Mosaic, stretches around the central exhibition space concluding with a small sampling of contemporary Judaica. While the museum maintains an active exhibition schedule, films and public programming, there is nonetheless a sadness about the setting. A video monitor lecturing on Jewish history occupies the place of the holy ark while the main Jewish population has moved on to other neighborhoods.

Shalom Y’all, based on the a book of the same name, juxtaposes forty-four large black and white photographs by Bill Aron with textual testimonies collected by Vickie Reikes Fox between 1986 and 1999. The text reveals an important dimension behind the images, exposing the history, experiences, fears and anxieties of Southern Jews. Therein lies the genius of the exhibition.

The photos are divided into five categories creating a conceptual framework. “Road Trip” documents the geographical range of Jewish merchants reflected in town names and Jewish business scattered throughout the South. “Lox, Bagels and Grits” features happy cooks busily preparing challahs, schnecken and matzo balls. Two hopelessly charming five year old twins from Russia proudly hold fresh baked challah in the Jewish Community Center Nursery School in New Orleans, Louisiana to prove the obvious centrality of food to Jewish experience. “Southern Ties” provides additional portraits of Jewish Southerners who have been mainstays of their communities for most of the twentieth century. They are the Jews who remember to remember. The wall captions and texts from the book allow a more complex picture of Southern Jewishness to slowly emerge. The text next to one beaming older couple reports; “My father’s mother was born in the South, a true Southerner. Her religion was that she didn’t eat bacon on Saturday.” The threat of assimilation wafts through the exhibition like the smell of cooking through an old house.

The images shift from celebration to introspection in “Peddlers, Planters and Politicians” showing proud owners of dry goods stores alongside demoralizing store closings and the demise of businesses that flourished for a hundred years or more. Diversity and success stand alongside failure and the evaporation of once thriving communities as the Jewish South shifts from small towns into the larger regional centers and cities. A close reading of captions proves sobering.

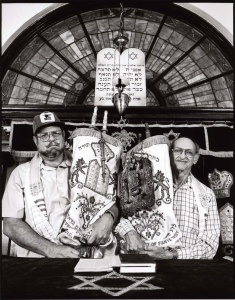

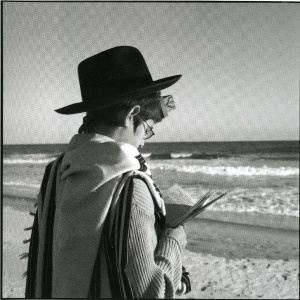

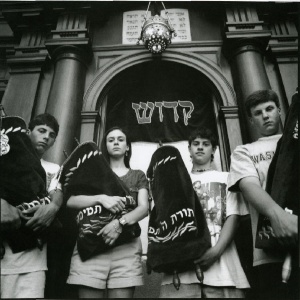

Communal life in “Magnolias and Menorahs” further plumbs the complex currents of Southern Jewish life. Struggling minyans in small towns contrast with thriving youth groups in larger congregations to present a Jewish community in the throes of change and challenge. Two members of Congregation Ahavath Rayim, the last Orthodox synagogue in Mississippi, proudly stand with their seferei Torah. They are a determined testament to a tradition that was long ago challenged by the first Reform congregation in the United States (1840) of Kahal Kadosh Beth Elohim in Charleston, South Carolina. The strength of the Reform movement is presented in a rehearsal for tenth grade Confirmation ceremony in Birmingham, Atlanta and a havdalah service at the North American Federation of Temple Youth Camp at Utica, Mississippi. The boys and girls, clad in shorts and tee shirts, look happily All-American in their youthful commitment to Judaism. The strangely provocative image of “Avram Aizenman” at Myrtle Beach, South Carolina provides a stark contrast. This young man, the son of the rabbi at the Chabad Day School, is seen praying the morning service in tallis and tefillin at the ocean’s edge. Within the context of this exhibition he seems foreign and not “typically Southern.” He is pictured next to a similarly atypical image of Reuben Greenberg, the Chief of the Charleston Police Force and member of the Conservative synagogue Emanu-El. Clad in tallis and kipah holding an open Chumash, this Black Jew is dignified, serious and clearly distinct from stereotypical notions of American Jews.

These deceptively simple “Images of Jewish Life in the American South” exposes much more than the anomalies of a diverse Jewish population. Alfred Uhry, celebrated playwright, comments in his introduction that “they weren’t black and they weren’t exactly white. They were just Jews…they just hung on.” American Jews in the South faced dual aspects of being different. The overwhelmingly Christian South never failed to remind them that they were Jewish just as they were constantly prodded by their fellow Jews that they were Southern. The latter condition was easily adjusted to, the former would prove to be considerably more complex. In caption after caption, especially as one peruses the book that offers additional testimonies and images, the role of being a Jew in a Christian world was never far from consciousness.

Each individual frequently feels that “You are the Jewish community, whether you like it or not…You do those things that are expected of you. You go out of your way to make sure that you do not cast aspersions upon the Jewish people by your individual actions.” Being different is central to Southern Jewish consciousness. “The first time I realized I was really different was during high school when I was not invited to join a sorority because I was Jewish. My best friend was invited and she joined and we weren’t good friends after that. Years later at our thirtieth high-school reunion she came up to me and said, “Do you remember when I asked to join the sorority and you weren’t? I always felt badly about that because that meant that you weren’t saved.’” For a newcomer in the South frequently the first thing you are asked is “What church do you go to?” This barrage of religious belief produces a wonderful clarity of Jewish identity not fully experienced in many other parts of the country.

The Jewish Museum of Florida has added to the exhibition dozens of family photographs, documents and anecdotes that trace the “Florida Connection.” A state by state survey depicts 33 families who finally made Florida their home after more than a century of contribution to Southern Jewish life.

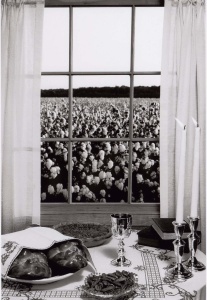

The most moving image of the exhibition is a still life, Shabbat in the Mississippi Delta. The small round table is set with two shiny challahs under a simple cover. A pecan pie, a dish of pecans and a full Kiddush cup sit opposite two seforim and lit Shabbos candles. All is ready for Shabbos as we gaze out the white curtained window to sunlit cotton fields that stretch from the house to the distant trees. We are inside and confident in our faith and tradition while the South, epitomized by the mixed legacy of cotton, slavery, cultivation and rural life, is never far from our gaze. It is a world in which Jews, Southern Jews, are on the front lines with Christian America. Perhaps that is why the favored greeting is Shalom, Y’all.

Shalom Y’all: Images of Jewish Life in the American South

Photographs by Bill Aron, Text by Vicki Reikes Fox

Jewish Museum of Florida

301 Washington Avenue, Miami Beach, Florida

www.jewishmuseum.com