The Mystery of the Sassoon Torah Shields

A set of Torah shields recently exhibited by Sotheby’s isn’t just beautiful—it also contains a hidden biblical portrait of the court Jew’s inner conflict.

Published in Mosaic February 10, 2021

Once in a great while Jewish visual culture rises to great heights, often to flicker brilliantly and then subside in the winds of societal change. We are privileged to witness the products of one such efflorescence at Sassoon: A Golden Legacy, a Sotheby’s exhibition and auction this past December that presented a wide range of Jewish artifacts collected by the Sassoons, a family of Jewish traders and financiers based in Iraq, India, and China who came to be known as “the Rothschilds of the East.” Two of those artifacts in particular show a combination of artistic mastery, Talmudic and biblical scholarship, and abundant capital the likes of which we have rarely seen. What’s more, the stories portrayed on them present a minor mystery, one that when looked at from the right angle resolves into a remarkable portrait of the man who ordered them into being.

In late 18th-century Galicia, an unknown patron, possibly named Isaac, commissioned from an artisan named Elimelech Tzoref the creation of three silver Torah shields. Tzoref (a surname derived from the Hebrew for gold and silversmiths) was a highly skilled goldsmith likely working in Lviv, Ukraine, a city then known as Lemberg. His skill and intelligence created objects that represent a singular moment of Jewish craftsmanship, creating, in the words of Sharon Liberman Mintz, Sotheby’s senior Judaica consultant, “three of the finest Torah shields in existence today.”

These three shields, remarkably similar and yet distinct, were subsequently collected by the Sassoon family sometime before 1887, when they were lent to the 1887 Anglo-Jewish Historical Exhibition at the Royal Albert Hall in London. One, signed and dated in Hebrew, sold at the December Sotheby’s auction for the staggering price of $1,350,000 to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. At the same sale, the second Torah shield sold for $685,500 to a private collector; the third shield had previously sold in 2000 at Sotheby’s Tel Aviv for the then-record price of almost $800,000. (In 2010 it was subsequently donated to the Israel Museum.) Taken together, the three shields represent an intriguing essay in Jewish visual creativity where the public face of an artwork—the gold and silver front surface—serves to intentionally hide a very private narrative on the back, here comprising a finely engraved Torah illustration complemented by some diagrams of the Holy Temple in Jerusalem. It is this highly unusual dialogue between the front and backs that captures our imagination.

The form of the Torah shield is a relatively late entrant to the canon of Judaica. First appearing in late 15th– and early 16th-century Italian and German silver work, they’re an early-modern addition to Torah ornamentation, a category that also includes decorated Torah covers, tiks, textile wrappers, Torah crowns, cabinets, arks, silver finials (rimmonim) and pointers. Simple shields were first created to beautify the Torah and provide a holder for small plaques that noted the spot for a specific Shabbat or holiday reading. They were also often inscribed by donors to celebrate the birth of a child. (Over time the original inscriptions were often erased and overwritten with newer dedications.) Naturally the specific forms and inscriptions on these ritual objects varied according to regional congregational preferences. Galician and Ukrainian Torah shields, of which we can count the Sassoons’, were mainly dedicated to the birth of children and functioned as purely ornamental objects.

Since substantial amounts of silver and gold leaf were used to make the shields, and since the skills of the goldsmith/designer didn’t come cheap, it is almost certain that the only people who could afford them would have belonged to the elite class of court Jews. These bankers, administrators, and diplomats were essential to the functioning of many Renaissance and Enlightenment-era principalities, providing access to capital via their international connections and offering help in administrating the varied lands of the principalities. Such Jews rose to great power, which often put them in considerable personal danger. One of them, Joseph Suess Oppenheimer (1699-1738), known as Jud Suess, became the financial advisor to the Catholic duke of Wuerttemberg in Germany, implementing a program of autocratic mercantilism that enraged the duke’s Protestant opposition. When the duke suddenly died, his opponents seized power, arrested Oppenheimer, publicly hung him and displayed his body in an iron cage for all to see. Clearly, for a Jew of the time, success came with grave risks–which were balanced out by the rewards of objects like the Sassoon Torah shields.

These rewards were enjoyed in particular at home. The Sassoon shields are intimate objects specifically made for private home use rather than at a synagogue. Furthermore, they are not simply examples of conspicuous consumption. Rather, they are unique in ways unseen in practically all silver Judaica. No expense was spared to create them; that both sides of the shields, rather than one, are ornately decorated is unheard of. This is reinforced by the fact that the three were almost certainly made as a set for one very wealthy individual; they are identical in shape, share decorative motifs and materials, and within 90 years of their creation were collected as a set together by the Sassoon family.

Let’s take a closer look and see how special they really are, and what story they tell.

Outrageous Torah Shields

The fronts of all three Torah shields are graced with a beautifully pierced parcel silver gilt design (silver which has been gilded with gold) depicting two columns that frame the crowned Tablets of the Law. The columns on the shield purchased by the Boston Museum of Fine Arts are composed of the beautifully sculpted figures of Moses and Aaron, while the columns on the other two shields are elaborately foliaged and decorated, each resting above graceful peacocks that form the foundation of the shield. All the backgrounds are composed of intricate straps, bands, and foliage that morph into fantastic beasts in ways reminiscent of medieval illuminations. Six cameos in exactly the same locations on each shield depict the same animals (bears, sheep, oxen, deer, leopards, and, finally, elephants bearing ornate seats), which is a reference to a text popular at the time, Perek Shirah (“Chapter of Song”). This 16th-century Hebrew text, first printed in Venice, is composed of seven chapters wherein all of creation sings a passionate song of praise to God made up of wide-ranging biblical verses. This visual program echoes and is derived from a nearby synagogue in Lukiv, Ukraine and its carved-wood Torah ark and its ceiling paintings that also embody the concepts of Perek Shirah. The shields by adopting these ideas and by presenting the awesome authorities of the Torah itself, Moses and Aaron, basking in the supernal praise of all creation, brilliantly reflect this familiar Jewish world.

The Other Side

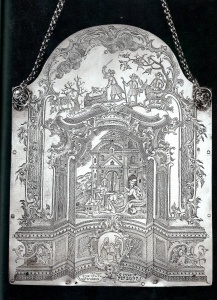

The back sides of all three shields likewise share a motif: the Binding of Isaac. The climactic moment of the story from Genesis in which the prophet Abraham nearly sacrifices his own son Isaac appears right to left in the arches at the top of the shields. The donkey, Ishmael (Abraham’s other son), and Eliezer (his servant) are waiting on the side; Abraham’s arm is raised grasping the knife about to slaughter Isaac on an altar; the ram Abraham will sacrifice instead of Isaac is caught in a tree branch on the far left; an angel in a cloud points to the ram. Strangely, Isaac is shown hogtied with both feet and hands bound together up in the air.

This awkward and shocking depiction is highly unusual.

Among the multitude of images of the Binding it is virtually unheard of to depict Isaac this way, that is, on his back, hands bound to feet. The only image that might have served as the artist’s visual source is an equally rare woodcut found as a pressmark at the end of tractate Zevahim in a 1616-20 edition of the Babylonian Talmud printed in Krakow. What this strange pose means is unclear in and of itself; luckily, its meaning becomes clearer when considered in the context of the rest of the shields.

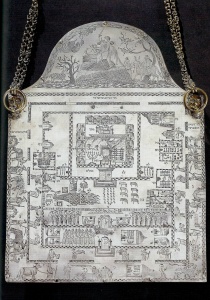

The very finely engraved images on the rear of all three shields consume the entirety of the remaining surfaces and set the narrative agenda. Two share a distinctive motif, an aerial view of Solomon’s Temple taken from a printed plan of the Temple found in some 18th-century editions of the Talmud. To that plan the four cardinal directions were added, thus more firmly locating the shields’ image in a real geographic location; likewise Tzoref the goldsmith added people and sacrificial animals to bring the illustration alive. Around the three edges of the shield a parade of ten worshipers march carrying animal sacrifices, while in the next inner register another fourteen worshipers carry several kinds of meal, wine, and oil offerings. In the women’s courtyard (the somewhat misleading name for the Temple’s outermost enclosure), five elegantly clad men stand at the ready, whereas the Israelite courtyard (located slightly closer to the inner sanctum) is crowded with at least fourteen men dressed in their finest 18th-century robes and hats praying, while right above them is an ensemble of seven Levite musicians. Taken in sum, the extraordinary details shown here provide an intimate glimpse into what may be the ceremony of bikurim, when the first fruits of the year were brought between Shavuot and Sukkot.

It is clear that Tzoref was a very learned Jew indeed. Everything we know about the Temple service is included here; even the Ark of the Covenant crowned by the winged Cherubim is seen in the Holy of Holies. These images alone are an explicit kind of prayer for the Holy Temple. As Sharon Liberman Mintz notes in her Sotheby’s essay, of those who look upon the shield “before opening the [Torah] scroll, they would see themselves literally placed among the worshippers in the Holy Temple.”

The Stolen Blessing Mystery

We’ve seen many strange and beautiful things on these glorious Torah shields so far. Perhaps the strangest element of all is found within a rococo architectural framework on the rear of the shield now in the Boston Museum of Fine Art. It shows the famous episode in Genesis where Jacob, under the hovering insistence of his mother Rebecca, masquerades as his first-born brother Esau and lies to his old and blind father Isaac to steal a final blessing meant for the first born. In the background here, the simple Esau is seen dutifully hunting a deer for his father’s favorite meal.

If portraying this episode is a way of referring and paying homage to the patron who commissioned the shields, as some commentators have asserted, it is a bizarre narrative to choose. Among all possible biblical episodes involving Isaac, this is the least flattering. Isaac, after all, is deceived in it by trickery and manipulation that results in Jacob fleeing for his life and causes eternal enmity between him and his brother. The mystery doubles when looked at together with the other portrayal of Isaac above it from the Binding, in which the patriarch is shown hog-tied on his back.

Isaac hog-tied and bound above contrasted with Isaac outwitted below—what can this puzzling combination of narratives mean? It is, in my opinion, no less than the unfolding of a double narrative reflecting upon both the name of the man who commissioned the Sassoon shields, very likely a Levite named Isaac, and his perilous status as a court Jew in the late 18th century. The inclusion of the Binding is a testament to the piety and commitment of Abraham and Isaac, which will stand to the credit of all Jews to come. And just as the Binding is something all Jews today benefit from, so too, in a circuitous way, is the stolen blessing. Rebecca knew in her heart that Esau was not the proper man to carry the Abrahamic blessing to the next generation, and that the precious covenant could only be borne by Jacob, thus justifying the deceit. We all, therefore, owe Rebecca our gratitude, and in this light Isaac is an unwitting hero, just as Abraham is for his willingness to listen to God. On the shields, these episodes come to reflect the perilous position of the court Jew. A man of power and influence, the court Jew also often became estranged from his own community and became stranded among Gentiles who would tolerate him only as long as he was useful. Once circumstances changed, he was extremely vulnerable, much like Isaac bound with his hands and feet up in the air. All he could hope for is a measure of understanding from his descendants, like the measure of understanding that the depiction here extends to the biblical Isaac.

This highly unusual and complex visual program reveals an extraordinary depth of Torah learning, psychological insight, and sophisticated craftsmanship on the part of the artist. Tzoref’s skills, in conjunction with the wealth and sensitivity of the unknown patron, have given us three masterpieces of 18th-century Jewish art. The rare occurrence of a Hebrew signature—“The work of my hands, Elimelech Tzoref”—and date of 1782 indicates the evident pride the artist felt for his handiwork. These Sassoon Torah shields present a unique dialogue, one with more than half its meanings facing the sacred Torah itself and thus intentionally invisible to the casual viewer. They are a very personal meditation of one Jew named Isaac, a dialogue between him and God about his most private beliefs and fears, told through coded Torah narratives.

I am deeply indebted to Sharon Liberman Mintz’s catalogue essay, as well as the advice of both Shalom Sabar, professor of Jewish art and folklore, and Simona Di Nepi, curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, in researching this essay.