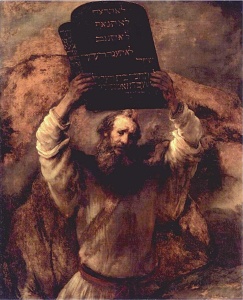

Connections: Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law by Rembrandt

Rembrandt’s Moses reaches up grasping the Tablets of the Law as he descends the holy mountain. Firmly rooted in the mundane, the painting presents us with a startlingly image of Moses’ initial journey down the mountain, carrying the first Tablets aloft, simultaneously displaying the prized gift and threatening to destroy God’s handiwork.

We know that the actual Tablets were but a physical embodiment of the holy Covenant between God and the Jewish people. This covenant of obedience had been verbalized previously in Shmos 24:3-7 by the people saying; “All the words that Hashem has spoken, we will do.” But now, after forty days in the presence of the Creator of the Universe, Moses was commanded to return to the Jewish people. He had successfully diverted God’s wrath over the sin of the Golden Calf, but now he had to deal with a rebellious people. And the Tablets, what to do about the precious Tablets made by and inscribed by God. Rembrandt even suggests their supernal origin in the symbolic white letters on black stone reflecting white fire written on black fire. How could they exist amongst such a sinful and distant people.

The painting is large for a single figure composition and has a powerful effect on the viewer totally lost in reproduction. It is five and a half feet tall and four and a half wide. The figure of Moses, slightly larger than life size, easily dominates the viewer standing before it. And yet Moses is not overly dramatic or stereotypically heroic. Quite the contrary, the painting’s power comes from the subtle lighting, innuendo and originality of composition. Considering that this was painted in 1659 Holland, late in Rembrandt’s career, the composition is shockingly cropped. The Tablets just reach the top of the canvas constricting any sky on both sides and the torso of Moses abruptly stops just below his waist. Suddenly you realize he is trapped. In fact, right in front of him on the lower right is a waist high bolder that blocks his path as surely as the giant boulders behind him.

Because of the enormity of the sin of the Jewish people with the Golden Calf Rembrandt understands that Moses is forced to destroy the God-made Tablets. Moses’ dilemma, his struggle, is expressed in the narrow, shallow and confined pictorial space. The object closest to the viewer, Moses’ hands, is only slightly more projecting than the outline of the stone ridge behind him. This constrained visual space in conjunction with the imposing size of the painting pushes the emotional action of the painting out onto the viewer, into our world.

The nature of this struggle that Moses experiences is revealed as the light slowly builds from the bottom of the composition. His torso is delineated by a soft light from the left side that also reveals the rocks directly behind him. Then the forms become unclear as the faint light shifts over his cloak and shirt until suddenly his powerful arms are illuminated in a flash of intensity. Heavy folds are outlined and a bit of massive forearm is revealed to support the two enormous black tablets. But because his hands disappear into shadows and material of the tablets themselves and the fact that tablets are thin and insubstantial, it is not certain whether Moses is supporting the tablets or perhaps they are supporting him.

The face of Moses returns us to certainty. It is boldly lit and directly in the center of the painting, The light striking his forehead, nose and cheek creates the deep furrow between his eyebrows. The very strength of Rembrandt’s painting forces us to consider the interior vision and understanding of Moses the man who has just spent forty days with God and must confront His people.

This is a visual dialogue between the top of the painting and the bottom. The background and the physical setting are barely articulated and therefore irrelevant. All that matters is the struggle in Moses’ mind as he tries to mediate between the Divine realm, represented by the weightless tables above him, and the obstinacy of the Jewish people before him.

The dumb rocks he stands among, blocking his path, restricting his movement, becomes a metaphor for the human dilemma. We are so rooted in the mundane that at the height of our Jewish spiritual development, after verbally accepting God’s covenant, we can still become lost and afraid and grasp at the cheapest palliative of idolatry.

Rembrandt’s genius in this painting, Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law, is to express the pain and sorrow that Moses must have felt when he realized that indeed we as a people could draw close to our God, but that the process could only be learned slowly and, unfortunately, painfully, over the years to come in the wilderness. Our connections with God, based on His Law, would not be easy.

2 Comments

Lakendra Kupper

You’ve made some really good points there. I checked on the net for more information about the issue and found most people will go along with your views on this web site.

Philip Corey

Great painter he was influenced by Caravaggio who was the greatest painter of the human figure + daring Rembrandt is looser with his brush work but also amazing