Ben Schachter’s Eruv Maps

In the world of art and culture the rabbis generally get a bad rap. From time immemorial they have often been thought of as the prototypical zealous guardians, seen as prohibiting all sorts of imagery with righteous abandon, constantly erecting walls to guard against anything that might be tainted with idolatry. Many might even argue that the pursuit of the visual arts, whether representational or abstract, to be no more that “bittul Torah,” a waste of precious time.

While a careful examination of the wide range of responsa available and the amount of Jewish art and synagogue decoration that has survived and continues to be created shows that this portrayal is both distorted and inaccurate, nonetheless the characterization persists. Therefore it is with considerable satisfaction that I have come to the conclusion that the very genesis of Jewish visual art can be found in a single act of supreme rabbinic creativity. The fascinating Eruv Maps by Ben Schachter, currently part of the Envisioning Maps exhibition at the Hebrew Union College Museum, has forced me to this conclusion.

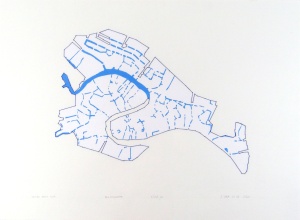

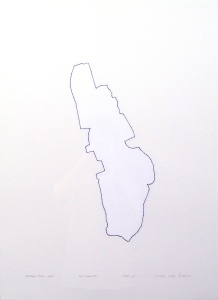

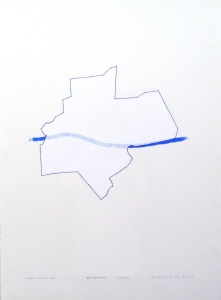

Schachter’s images are deceptively simple conceptual artworks. Each drawing is made of paint, graphite and thread on heavy watercolor paper. The images are of an unadorned outline in blue thread of the borders of a specific eruv in communities around the world. In this exhibition he features the following eruvim: Squirrel Hill, a neighborhood in Pittsburgh, PA, Sharon, MA; Manhattan, NY and Venice, Italy. To someone unfamiliar with the specific location the drawings are elegant abstract shapes and yet when a location is recognized, it leaps to life as a remembered physical reality that one has walked through and lived in on a cherished Shabbos. That was my initial reaction to the Eruv Map of Venice. But these works do much more than recall a memory, they in effect document a reality that is profoundly abstract and fictional. The fiction of the two dimensional drawing done with string, directly reflects the very real fiction of the eruv itself, frequently constructed with string, a brilliant rabbinic construct that astoundingly pushes aside a Biblical prohibition. And that is only made possible by the genius of the rabbinic sages in the Mishnah and Gemara in Eruvin, codified close to two thousand years ago.

In giving the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai the Torah says in Exodus 20:8-10, “Remember the Sabbath day and keep it holy… you shall not do any work…” From this the sages of the Mishnah in Shabbos 7:2 derived that there are 39 categories of work that are prohibited by this verse in the Torah. This definition of “work” is deduced from the juxtaposition in Exodus 35:4 of the commandment to construct the Tabernacle with the repetition of the prohibition of “labor” on the Sabbath. The 39th prohibition is transferring objects from one domain to another domain. The first Mishnah in Shabbos, extensively discussed in the Talmud, delineates four different domains; private domain, public domain, exempt area and semi-public domain. The Mishnah and the Talmud make it abundantly clear that it is a Biblical violation to carry an object from the private space of one’s home out into the public street on the Sabbath.

In what at first seems paradoxical the sages of the Second Temple period devoted an entire additional tractate to redefine this Biblical prohibition by instituting the device of the Eruv. Simply put the rabbis maintain that if one encloses additional areas beyond a private domain, they can be merged together into one larger private area where carrying from place to place is perfectly permissible.

The fact that an area may be enclosed and combined by means of walls and partitions is hardly surprising. But the notion that a valid partition can be made of two upright poles connected by a horizontal pole or wire with nothing else between them shows rabbinic creativity at its most audacious. It is based, like many things Rabbinic, on the logic of definitions. If an enclosure by its very nature must have an entrance, therefore entrances are essential; in fact an enclosure may be made up entirely of entrances. Many modern Jewish communities throughout the world utilize this principle to construct an eruv.

Over the last two years Ben Schachter has created twelve Eruv Maps including Riverdale, NY; Park Slope, NY; Teaneck, NJ; Los Angeles, CA and Cambridge / Somerville, MA. He has images of an additional sixty at the ready. Most are remarkably similar, elegant abstract shapes delineated by blue thread painstakingly threaded through upwards of 200 holes in the thick paper, mimicking the countless poles and wires that constitute the real eruv. The blue thread echoes both the actual wire that makes up many of these partitions and the blue techeles in tzitzis that similarly must be seen to remind us of our mitzvah obligations. The eruv wire warns us that we may carry no further than its boundary just as tzitzis and techeles confine us within the boundaries of Jewish law.

Some of his Eruv Maps are more complex, like the one of Venice that schematically shows in blue the countless canals that by definition are excluded from the permissibility to carry. Likewise the Squirrel Hill Eruv is bisected by a blue line that represents US Highway 376 that runs through its middle. The white of the eruv is painted over this line since the highway runs through the Squirrel Hill Tunnel with the eruv intact above. In yet another work the artist has one large conglomeration of eruv images in Sixteen Eruvim I’ve Walked Through. Here the shapes are even more abstract, butting and overlapping one another, in what Schachter imagines is a visual combination of these far-flung Jewish communities.

Central to Schachter’s project is the overarching notion of drawing that creates boundaries, borders and limits. The vast majority of these drawings are on unprepared white watercolor paper, pierced by blue thread that draws the shape of the eruv. The interior of the eruv is itself painted white, only slightly distinguished by a cool white impasto. He has stated that; “As a contemporary artist I see these structures [eruvim] as drawing in space.” And that is exactly what the rabbis of two thousand years ago intended. The rabbis created the consummate theoretical border, conceptualizing space as a reality that can be manipulated, and in fact, redefined by the lightest of touches. They created a reality that flies in the face of common sense by using poles and wire to simply draw in space.

The Jewish visual artist creates a fiction that becomes a reality. The artwork becomes a real object, whether painting, sculpture, drawing or graphic, that exists in the world. But more importantly an artwork creates a reality of meaning that reverberates in human consciousness; challenging, creating, changing and affirming ideas and perceptions that once were dominant and now are changed by a new meaning. In a metaphorical sense, all art draws in space, creating something out of the intangible, creating meaning where there was previously just empty air. And that is what our sages have done by creating the concept of the eruv; they have created a wall out of thin air.

The rabbinic creativity of the eruv was the beginning of Jewish visual art.

Ben Schachter: Eruv Maps

Envisioning Maps: Hebrew Union College Museum

One West 4th Street, New York, NY