At The Library Jewish Theological Seminary

And if Not Now, When?

When you see a talmid chacham pass by, you stand up to honor him and his learning. You then return to your own learning inspired to do more and to learn deeper. The same holds true of an artist visiting a great art museum. One stands in awe of a masterpiece and returns to the studio inspired and invigorated by the creativity one has witnessed. I am hoping that something similar will occur when you visit “Precious Possessions” at the Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary. And, if not now, when?

Over eighty treasures of manuscripts and printed material make up this splendid exhibition curated by Sharon Liberman Mintz, Elka Deitsch and Havva Charm. The objects have been selected from the Library’s enormous collection of 11,000 Hebrew manuscripts, 20,000 rare printed books, the world’s largest collection of incunabula (very early books printed before 1501) and 30,000 fragments from the Cairo Genizah. The exhibition presents us with a wonderfully broad range of hand made manuscripts, printed books and incunabula, ketubbot and megillot in addition to broadsides (a document printed on one side intended for mass distribution), prints, Americana, music, bookplates and postcards.

Not surprisingly, the exhibition fills one with pride at the sheer scope of the Hebrew and Jewish printed word. One can see first hand that we are and always have been a people of the Book. You will see the first page of the Gemara Berakhot, the first volume published by the Jewish Soncino family in Italy in 1483 and one of the earliest printed versions of the Talmud. Nearby is the first published edition of the Mikraot Gedolot of 1524 by one of the earliest and most prominent Christian printers of Hebrew books, Daniel Bomberg. Hayyim Shahor and Meir Mihtam, one of the first Jewish printers working in Prague, printed a mahzor shown here in 1525. It is a masterpiece of Hebrew typography set within a wonderfully elaborate decorative border.

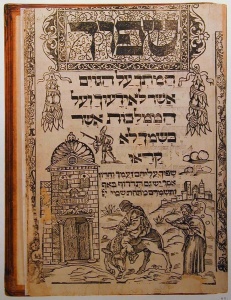

The Haggadah from Mantua of 1560 is open to “Pour out your wrath on the nations that do no know you.” This page is part of an iconographic trend in Germany and Northern Italy at that time showing the arrival of the Messiah riding on a donkey, heralded by Elijah blowing the shofar. This haggadah’s depiction of our yearning for moshiach is as strong and stirring an integration of sacred text and vivid image that you will find in any haggadah from any era.

All of the above is but a prelude to the stars of this exhibition, the illuminated manuscripts. These are the real challenges to us that should inspire artist and patron alike. The 1454 haggadah of Joel ben Simeon, a Jewish scribe-artist, is a prime example of an artist working in the Ashkenazic and Italian illuminator tradition. The instructions for the seder are set within elaborate decorative double arches, festooned with fantastic towers and figurehead medallions, all supported by wild and domestic beasts and crouching figures. Fifteen of his unique and signed illuminated manuscripts have survived to inspire us with his Jewish creativity in the service of hiddur mitzvah. Is it possible the Jews of the fifteenth century in the Rhineland and Italy were more affluent than our communities are now?

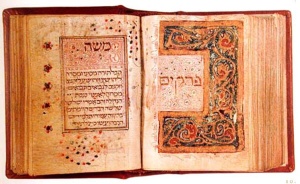

The Portuguese siddur from the late fifteenth century, open to the beginning of Pirkei Avot, is achingly beautiful with a title page of floral pattern laced with gold that proclaims “Prochim.” On the opposite page the first chapter opens with “Moshe,” emblazoned in gold letters, and set off in a delicate panel of pink filigree penwork. Imagine the rabbi of your shul teaching pirek on Shabbos afternoon with a siddur as beautifully made by a contemporary artist.

The pride and joy in Tanach is immediately understood in a German Bible from the year 1300. “Ish,” the initial word of the book of Job, is framed by a micrographic border of the masorah that becomes a hunting scene of a stag followed by two hounds. The inventiveness and creativity of this monumental volume expresses, in subtle artistic language, a devotion to the word itself that makes the Hebrew language tangible and vibrant. Certainly we haven’t forgotten the meaning and beauty in each word of our holy texts. The commentators delve into each word for meaning, why should the books we learn with not reflect our similar passion and devotion?

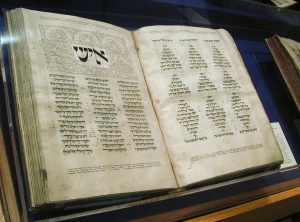

Finally, can you imagine the impression that Yom Tov would have on any congregation if when the sheliach tzebor came forward on Rosh haShanna and opened a mahzor as impressive as the enormous Esslingen Mahzor, created by the Jewish scribe and artist Kalonymus ben Judah in Germany in 1290.

This monumental mahzor (each page is 20” high and 14” wide) was meant for use in synagogue and I am certain that whoever the chazzan was from year to year, he commanded absolute attention as he began the piyut, Melech (O King who is girded with strength) and turned page after glorious page of this masterpiece.

When you see these objects and stand next to them, (not just look at one page in a reproduction) you will begin to appreciate the depth of love, devotion and faith that the patrons and their congregations expressed through illuminated manuscripts that made up the sacred texts of their community. Our devotion is no less than theirs. Our expression, in terms of the Jewish art of manuscript illumination, unfortunately falters.

Today we see illuminated haggadot, ketubot and megillot that are continuing the traditions begun by the masterpieces in this splendid exhibition. There are a very few contemporary artisans who have made illuminated benchers to be published in small editions, and at least one luxury limited edition of an illuminated Pirkei Avos. Unfortunately, by and large, the field of hand made luxurious seforim made for use in the synagogue has been abandoned. And as far as I can ascertain, there is no good reason for this. We have large affluent communities of pious Jews all over the globe that routinely adorn their shuls and holy objects. The patrons of the Jewish communities are ready and able, as are Jewish artisans. A shidduch needs to be made to again create magnificent contemporary communal Tanachim, Siddurim, and Makzorim.

Go and see Precious Possessions; you will be inspired by the glories of Jewish creativity. Then ask yourself in the words of Pirkei Avot 1:14; “And if not Now, When?”

Precious Possessions

The Library of the Jewish Theological Seminary

3080 Broadway, New York, N.Y.