Paintings by Diana Kurz

Reaching back in time to reclaim a family for herself and, in a yahrzeit moment, to rekindle lives snuffed out, Diana Kurz’s paintings stand as testaments to victims of the Holocaust, one by one. After a successful 20 year career as an artist and teacher (with a strong feminist bent), in 1989 Kurz happened upon a few surviving photos of her own relatives “who disappeared during the war.” Suddenly her past opened up and possessed her. Recently this spring (April 4-May 2, 2012) a series of these paintings was shown at the Art Gallery at Kingsborough Community College, CUNY.

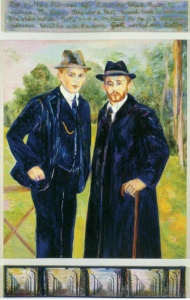

Brothers (1999) seems to depict a world of normalcy itself. The two men; one with a cane and bearded, possibly older, and the other clean-shaven with a lighter colored hat, stare out at us innocently. Simply a snapshot from two lives. The work is notable for its simple composition; each figure echoing the other while the subtle differences reveal the kinds of simultaneous contrasts and similarities that dominate familial relations. Then we read the caption at the top: “The brothers Pietnicer left Krishenka, Poland trying to escape the Nazis. They were last heard from in 1939 when the older brother, Zelig, sent a postcard to the US from an unknown location with the words: ‘Gott wird uns helfen!’ ‘God will help us.’” Along the bottom of the image is what appears to be a filmstrip depicting barbed wire double enclosures characteristic of work and death camps. Kurz summons two lives back from the grave to memorialize them and remind us of the simple details of tragedy. She commands us to just remember, and now, after her painting, we cannot forget them.

Diana Kurz’s history curiously buried her relationship of the Shoah until a chance encounter uncovered an entire life she never knew. She was born in Vienna and escaped as a young child with her family in 1938, finally arriving in New York in 1940. As was fairly normal for many refugees, the past was kept silent and every effort was made to acculturate as “normal” Americans. When she was ten, two cousins who had survived the concentration camps arrived and lived with her family, sharing Diana’s bedroom. Naturally teenage stories were exchanged that would lurk in her memory forever. And yet she grew up, when to Brandeis for a BA and an MFA from Columbia, and began a successful career as a figurative artist and teacher. Only decades later in 1989 when she was visiting an aging aunt did she happen to see old photos of her family in pre-war Vienna. Suddenly she had to confront the suffering and loss of her family that did not survive. As a mature artist she was able to summon the aesthetic tools to approach a history that was both deeply personal and yet relevant to the Jewish people and all humanity.

Kurz brings something unique to her Holocaust paintings. All of the paintings have a personal edge since the impetus for these works stems from photographic portraits of her family members, i.e. the emotions are rooted in her own past, regardless of whether she remembers the individuals or not. In each image at least one subject is looking directly into the eyes of the viewer, confronting us as virtual family members and imploring us to remember them as individuals that we deeply care about. It is as if in the act of visually engaging these paintings we are saying kaddish for each person depicted.

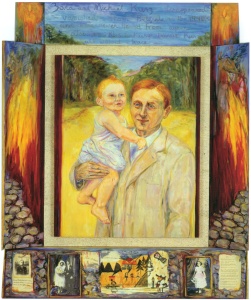

Drawing upon the European medieval tradition of depicting important religious subjects with altarpieces that had multiple side panels and predellas (small independent images along the bottom of the main image), Kurz utilized this form in the early testament to her uncle Michael and cousin Zora. He is shown holding his infant daughter in what were clearly happier days. The image is sun-filled, ominously contrasting with the fiery turmoil that surrounds them in the side panels. The predella presents a seemingly normative past; an army portrait, a wedding picture, a postcard, a studio portrait and an innocent childhood drawing (actually by children in Theresienstadt) while the enormous artwork (75” X 60”) is capped with two memorial candles and the harrowing dedication against a bright blue sky; “Zora and Michael Kurz disappeared—vanished—from Belgrade in the 1940s and were never heard from again—also Klarcha Kurz & Dorrit Kurz—all without a trace.” It is a painting of stark contrasts, evoking memories of lives erased and now brought back for us to mourn.

Another much smaller image of Zora depicts her as an even younger infant sitting up for her portrait while the caption that frames her along the edges tells us she was born in 1939 and was “hidden in a hospital in Belgrade… was discovered and murdered by the Nazis.”

In another very large painting (98” x 77”), Three, pursues the same testimonial motif, here utilizing a photograph of a father and his two young children taken in the 1930’s. The children were forced to wear the yellow star but the wounded veteran, proudly wearing his WWI medals, was exempt under the anti-Semitic Nuremberg laws. Eventually even these exemptions were abolished and all Jews faced deportation and death camps. Kurz’s stark portrait of absolute strangers dramatically bridges the familial gap and imposes upon us an intimacy and empathy seldom achieved in Holocaust art. They become our family because they are more than our People; they are a family we could have known all too well. A patriotic father who fought and suffered for his country, is simply trying to raise two children in as much normalcy as abnormal times might permit. And perhaps most horrifying, we know with almost certainty the fate that they could never have guessed.

In Dorrit and Michael Kurz (1990) the artist again focuses on her own family. By now we recognize Michael, here with his older daughter Dorrit posing in a somewhat more formal portrait against a railing and a village view out the window. Kurz’s painting style is matter-of-fact and disarmingly simple. Dorrit’s deep blue dress contrasts with her father’s grey suit just as her pretty red bow echoes his red hair. She stares pensively into the distance while he confidently confronts the camera. Their future seems to stretch endlessly before them. And yet the blank wall that formed the perfect backdrop now allows for the text’s bitter history: “Michael Kurz and Dorit deported in the 1940s from Yugoslavia to an unknown destination. They were never heard of again.”

Diana Kurz’s most powerful works in this series demands that we take notice of the devastating “normalcy” that pervades these images. It is perhaps this aspect of normalcy of each and every victim of Nazi terror that galvanizes our emotions to reach back through time and reconnect with these victims. The same emotions were summoned for me in the aftermath of a distinctly different tragedy. The New York Times from September 14, 2001 until the end of that year profiled 1,910 victims of the 9/11 attacks in a series called “Portraits of Grief.” The overwhelming sense I got from reading them and the theme that time and time again would tear out my heart was the overwhelming decency and normalcy of these innocents. It is this insight that makes Kurz’s work so riveting. By depicting the all-too-soon to be victims as simply normal individuals, the horror of the genocide against the Jews is fully revealed. We were not persecuted and murdered because of any crime, any characteristic or any trait that could be discerned. No, it was only as Jews, and here as Jews in the abstract, that the Nazis decreed death to us, our families, our people. It is the very normalcy of the victims that makes this crime so egregious. This is Kurz’s crucible that she exploits so well.

(The artist can be reached at [email protected])