Persian Jews at Yeshiva University Museum

Light and Shadows: The Story of Iranian Jews at the Yeshiva University Museum in New York reviews 2500 years of Jewish cultural history and survival in one Middle Eastern diaspora. Light and Shadows: the Story of Iranian Jews at Yeshiva University Museum is a totally different visual experience. This extensive exhibition of more than 100 objects originated at the Beit Hatfutsot, Tel Aviv and surveys more than 2,500 years of Jewish presence in Persia, known since the early 20th century as Iran. While this is primarily an intriguing historical exhibition chronicling the heroic as well as disastrous history of Jews in the Shite Islamic empire, it also features significant works of Jewish art.

The most exciting artifact is in the first section; the Cyrus Cylinder, dated from 530 BCE. This reproduction of the original in The British Museum, is a cuneiform inscription by Cyrus the Great, the founder of the Achaemenid Empire and conqueror of most of the civilized states of the ancient Near East. Seen by some as the “oldest known declaration of ‘human rights,” it specifically permits Babylonian captives to return to their homelands and religious practices. This historical proof of the Jewish return from the Babylonian exile, is overtly praised in Ezra 1:1-11 and reflected in Isaiah’s approbation of Cyrus; “So said the Lord to His anointed one, to Cyrus, whose right hand I held, to flatten nations before him…” (45:1-7). It is here that Jewish history leaps alive in the artifacts of an ancient civilization.

Future Jewish life in Persia had many trials and tribulations over the centuries but the establishment of a Shiite Muslim regime from the early 16th century well into the 19th century created an institutionalization of the oppression of the Jewish minority. According to Shiite belief Jews were ritually impure and therefore the slightest physical contact was anathema. They were discriminated against and forced to live in isolated Jewish neighborhoods called the Mahale. Forced conversion, mismatched and distinctive clothing, limited profession opportunity along with occasional violence kept the Jews subservient, even while paradoxically there was a traditional Jewish elite of doctors and healers essential to Persian society.

The intolerant nature of Persian society resulted in periodic attacks, including the pogrom in the city of Mashhad on March 26, 1839 resulting in the death of 30 Jews and the forced conversion of close to 2000, many of whom continued to secretly observe Jewish practices. Tens of thousands of their descendants are in Israel and New York to this day and many artifacts of their dual existence that were necessary for daily life are seen here including ketubahs that mimic Muslim marriage contracts, weekly Torah readings that imitate Koran readings, tiny tefillin boxes for secretive use and similar ruses. Nonetheless, Jews were able to operate on the fringes of Persian society even maintaining a surprising role in preserving secular poetry and musical traditions that Shiite tradition suppressed. Utilizing many videos the exhibition documents the notable contributions that Jews made to Persian society whenever they were allowed to exercise their natural creativity.

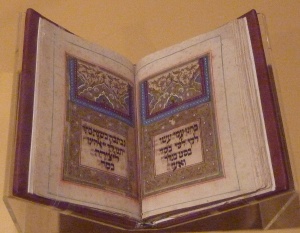

Not surprisingly in the literate and affluent Persian society all types of illuminated manuscripts flourished, including Jewish literature. Many of the manuscripts selected here, including those only represented in digital format, are amalgams of traditional Jewish texts, such as the Book of Esther (which has no independent historical basis), and actual Persian kings and history. Additionally poetic paraphrases of biblical stories based on Jewish, Islamic and Persian sources, such as Shahin-Torah Nama by Mawlana Shahin (1877) are seen here illuminated. Unfortunately these beautifully complex works that blend multiple cultural influences and visual traditions derived from the extremely rich illuminated Persian manuscript tradition are not adequately explained or shown to their best advantage. The manuscript Prayer Book by the Young Yosef Avraham Shalom Abd al-Raziq from Yazd, Iran (1860) is an exception, its well-lit and open presentation allows for a full appreciation of its beauty, skill and sensitivity.

Naturally ritual objects garner attention and the botah (paisley shaped design motif) Torah Finials (1933) ornamented with little bells are especially charming. This particular shape has deep historical roots in Persia from pre-Islamic times and more recently in Yazd wool fabrics and carpets particularly. These finials are not only religiously beautiful but proudly proclaim their national origin.

Another example of the complexities of cultural integration are the two artworks depicting the tale of Yusef and Zulaikha. There is an iPad presentation of the 19th century manuscript by Eliyahu ben Nissan ben Eliah from Mashhad, Iran and the early 20th century oil painting of the same subject from Tehran. Both are fascinating only if one actually understands the subject, which is a complex Islamic elaboration on the story of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife where her desperate pursuit of Joseph continues well after he is imprisoned. Unfortunately this background is not presented in the exhibition.

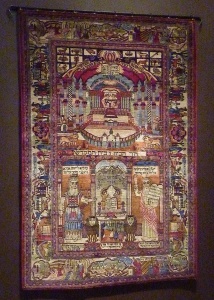

Equally surprising is the introduction of the entire exhibition with a large Kashan wall carpet from the Ben Ephraim Family Collection in Tel Aviv. This beautifully complex image presents an eschatological program starting with Moses and Aaron and the Mishkan on the bottom and proceeding up to the Temple Mount and the Sanctuary above, depicted in perspective as a kind of futuristic grand synagogue. Along the borders are depictions of Noah’s Ark and Sacrifice, Binding of Isaac, Sale of Joseph and Finding Moses in the Reeds. Further research reveals that the prototype of this carpet, “was presented by the Shah of Iran, Nasser-e-Din (1848-1898) to his Jewish doctor, Hakim Nour Mahmood in honor of Mahmood’s survival from an assassination plot by his envious colleagues.” (Jewish Carpets by Anton Felton, 1997; pg 156) And just as it is especially perplexing that none of this information is available in the exhibition neither is there an exploration of the extensive history and iconography of Persian Jewish carpets.

Yet, in spite of these omissions, Light and Shadows at YUM still serves as a significant introduction to the history and art of Persian Jews, and by their example, a courageous model for Jewish culture wherever it is found in our vast and sometimes troubled Diasporas.

Light and Shadows: The Story of Iranian Jews

Yeshiva University Museum – Center for Jewish History

15 West 16th Street, New York, N.Y.; (212) 294 8330

www.yumuseum.org

Sunday, Tuesday, Wednesday (8pm), Thursday; 11am-5pm: Friday; 11 – 2:30pm

$8 adults, $6 seniors & students

FREE: Monday & Wednesday 5pm – 8pm

Until April 27, 2014