Noah, the Dove and the Raven

“Hashem saw that the wickedness of man was great upon the earth…” It was as if His Divine patience had run out and as a result His attribute of strict Judgment overtook His attribute of Mercy (Akedias Yitzchak). God decreed that all of mankind was irredeemable and the rest of His creation that existed for man’s sole benefit was rendered useless, and so all was to be destroyed. All except Noah and his family.

Noah dutifully followed God’s instructions and built a massive ark to save a remnant of the animal creation and Noah’s family. God promised to destroy all and yet to somehow forge a covenant with Noah. No details, no time frame, only a pledge.

It rained and rained and the waters seethed as God had promised and Noah and his family witnessed the destruction of their entire world. Then it stopped and the waters slowly receded. Noah had no idea what was next. The future fate of all humankind resided in that drenched ark, now resting on a barren mountaintop. What was he to do? He turned to the birds.

Over the centuries both Jewish and Christian artists have been fascinated by the story of Noah. One of the earliest examples is the Vienna Genesis, an illuminated manuscript dated to the 6th century. Only 24 pages survive out of an estimated 96 but the story of Noah is prominent among the illuminations, including a depiction of the drowning populace, Noah’s exit from the ark, the establishment of the Covenant and the drunkenness of Noah. A later example is found in the mosaics of the entranceway to Saint Mark’s Basilica in Venice completed sometime in the 11th century. It is thought that those designs may have been based on another very early illuminated bible, the Cotton Genesis (5th century).

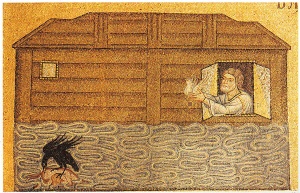

The Saint Mark’s mosaics contain no less than 14 separate scenes from the narrative. Of special interest is a scene of Noah leaning out of the ark window sending off the dove in search of inhabitable dry land that would signal the salvation of Noah and his family. A jet-black raven is in the lower left greedily devouring the carcass of a dead horse, unwilling to participate in the search for safety.

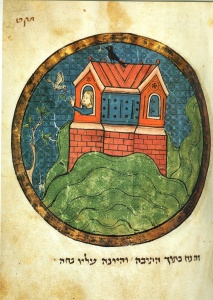

Another early image of this crucial episode is from the London Miscellany (MS 11639) from the British Library. This illuminated manuscript of biblical and religious texts, treatises on grammar, astrology, calculations and the Sefer Mitzvot Katan was probably created in northern France around 1280. Here the anonymous artist depicted the ark as a kind of little brick house set in a roiling green sea. Faint line drawings of fish are barely seen in the sea and a lone tree branch intrudes on the extreme left. The dove is returning to Noah with a freshly picked twig sporting two green leaves. Grimly watching over everything from the roof of the ark is the raven.

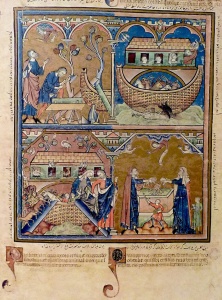

Right around the same time (ca. 1250) another extensively illuminated manuscript was made in Paris. The Morgan Library Biblical Picture Book sports 283 pictures with Latin paraphrases of the Vulgate Bible. The book illustrates the narratives from Creation to the Story of David, almost always showing four scenes per page framed with alternating blue and pink patterned borders. The story of Noah is seen in five scenes beginning with God’s command to build the ark. Noah is working with an ax on the timbers of the ark in the upper left panel. The upper right panel depicts a rather imaginative ark. The body of the ship appears to be handwoven wicker with the hold containing all the animals, their funny little heads peering out. Up above is an arched upper deck for Noah and his family. As in the earlier images, Noah is sending off the dove in search of land while the same dove is seen returning with a twig on the opposite side, a typical example of simultaneous narrative. Ominously, the raven is again seen feeding off the floating body of a horse.

Below, in a sensitive touch, Noah is helping his wife and sons to exit the ark via one ramp while the animals scamper off on another ramp in the lower left. Above them birds are tasting their newfound freedom flying off in every direction. In the lower right panel Noah offers his thanksgiving sacrifice with the help of his wife as two of his sons help out with the wood and lambs.

Matthaeus Merian the Elder (1593-1650), engraver and publisher, produced 230 images from the Bible, some of which were later adopted for use in 17th and 18th century haggadot. While not used in haggadot, he did include four images from the Noah story. Like many Renaissance and Baroque artists he concentrated on sweeping views of the animals entering the ark two by two, sufferings of the victims of the flood and the covenant of the rainbow. Similar in naturalistic temperament Gustave Dore (1832-1883), the French academic illustrator, reveled in writhing bodies dramatically dying. Interestingly the only image I found of the climatic “Noah Cursing Canaan” is by Dore. Unfortunately the image is simply a superficial costume drama of hyperbolic gestures.

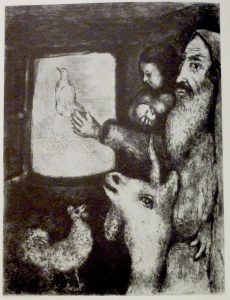

In Marc Chagall’s masterpiece The Bible, a suite of 105 etchings started in 1931 and finally published in 1956, Noah is represented by four images. Noah’s drunkenness is the only representation that is totally normative. The Rainbow represents the sign of the covenant arching over a Chassidically garbed Noah and features a winged angel sweeping through the sky along with the light-filled rainbow. The Sacrifice of Noah is also unique in that both Noah and his wife are offering the thanksgiving korbon, much like the Morgan Library Biblical Picture Book seven hundred years earlier. But it is his Dove of the Ark that most radically shifts our point of view. We see the dove being sent out from the inside of the ark, Noah, his wife and child, and the animals, anxiously observing his bold gambit to try to understand what he was to do next and whether it was time to leave his proverbial lifeboat.

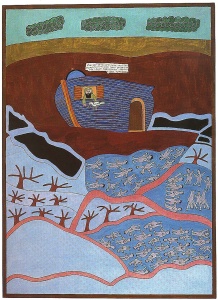

Shalom of Safed (1887-1980), the much-beloved primitive Israel artist, chose to depict The Dove Returns to Noah’s Ark (1963) with a startling new interpretation. As in many artists before him Shalom pictures Noah leaning out of the ark window, grasping the dove with a twig in his beak. The ark rests on barren soil but below it is the grim sight of dozens of pale drowned bodies. Looking closely we notice that they all bear identical Hitler-like mustaches, suddenly turning the ancient saga into a very modern morality tale about exactly how evil the old world was thereby necessitating its destruction.

This fascinating dialogue between Noah, the dove and something evil, sometimes just the raven and at other times sinful mankind, spans 1500 years of artistic contemplation about the nature of God’s terrible decision to destroy His creation. Remember the next time you see a rainbow His overwhelming compassion for His handiwork this time around.