Paintings from Midrash by Brian Shapiro

The midrashic world is a dangerous place to inhabit. It plays fast and loose with our sacred texts to fathom their deeper meanings, solve vexing textual and conceptual problems and, finally, make sense of the holy words in contemporary terms. Midrash is passionate and deeply creative, just as the current midrashic paintings of Brian Shapiro currently on view at the Chassidic Art Institute until December 8, 2011.

Shapiro is no stranger to Jewish themes; his enormous canvas, Generations, a tour-de-force of Jewish history, was reviewed in this column in August, 2010. Since then the artist has become increasingly mesmerized by biblical subjects seen through a midrashic lens. The lure of midrashic interpretation satisfies the need to know the details and specifics of many biblical narratives, i.e. the precise textures of how and why events unfolded in the devastatingly spare Torah text. For a figurative artist like Shapiro the multitude of midrashic exposition is a reassuring link with a tangible reality to anchor the text in this world.

Jacob and the Angel purports to depict the epic struggle between Jacob and a mysterious being who is either an emissary of God or the protecting angel of Jacob’s dangerous brother, Esav. Based on a midrash in Beraishes Rabbah the artist shows the angel holding Jacob’s hand over a roaring fire. While the midrash expounds that the angel stuck his hand into the earth and a volcano of flame erupted threatening Jacob, the painting doesn’t simply illustrate that event. Rather, if we observe closely, both figures are indeed struggling not only between themselves, but significantly repulsed by some unseen force off the left edge of the painting. In fact, both angel and Jacob are aghast at what they perceive. Indeed it is the mutual recognition that this primeval sibling struggle will reverberate throughout the millennia. It seals the fate of soon to be named Israel and the nation who will descend from him with a terrible and bloody future.

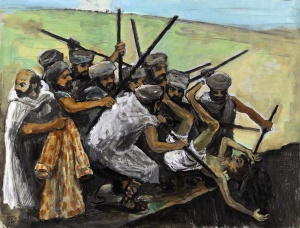

The theme of sibling rivalry and conflict is of course central to many Biblical narratives, not the least the foundational story of Joseph and his brothers. Shapiro’s Joseph and Brothers is terrifyingly on target. The brothers, all turbaned except one, appear to be engaged in what in contemporary Israel would be called a “lynch.” Most of the eleven have staffs that are used to threaten, push and drive the helpless half-naked Joseph off the edge of a precipice. What is extraordinary is the ferocious compact energy of brotherly hatred revealed in bright daytime clarity. A lone bare-headed brother is at the extreme left, looking away in concern as he holds Joseph’s many-colored cloak. In this one bald figure is all the cunning and unacknowledged guilt of fratricide. This figure represents none other than Reuben who pleaded with the rest not to murder Joseph and yet finally fashioned the vicious lie to his father with Joseph’s bloodied coat. Here the artist has, by thinking midrashically, actually summoned the literal biblical text most evocatively.

While much ancient midrash traditionally has the textual authority of the oral tradition transmitted by the Sages, it also must be seen in the dual contexts of the original textual “problem” and actual date the collections were finally redacted. Nonetheless, regardless of date, all Torah commentary remains a vibrant source of contemporary understanding of sacred text. Even a contemporary artist, passionate about the complexities of Torah narrative, can offer unique insights into the stories our tradition celebrates. Sea of Reeds is a significant example of Shapiro’s contribution to midrashic exposition. Significantly, in this exhibition the artist has explicitly offered his midrashic sources and explanations for each of the paintings.

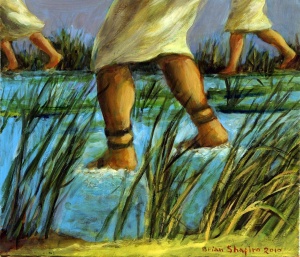

The parting of the Red Sea in the Exodus from Egypt is related as a simple miracle. And yet even the Torah itself ventures an explanation; first relating the means of the miracle (Exodus 14:21) “…and Hashem moved the sea with a strong east wind all night and He turned the sea to damp land and the waters split.” And yet one wonders how wind alone could render a sea into dry land. Shapiro offers a disarmingly simple image of the feet of three individuals appearing to walk on water in the midst of a reed swamp. In his text he explains that “In the Okefenofee Swamp in Florida, grasses have grown over deep water to form what appears to be a land mass. This will support men and women walking in an orderly fashion. However, when the Egyptians, using …a metal chariot…it is only a matter of time before the whole mass collapsed and horse and chariots… ‘dropped like a rock’ into their watery grave below.” Aha.

The visual midrash of Shapiro’s painting expands well beyond the biblical text into a contemporary American experience that nonetheless represents text in a deeply convincing manner. Walking on dry land indeed!

![Moses on Sinai [detail] (2010), oil on canvas, 30 x 30 by Brian Shapiro Courtesy the artist Moses on Sinai [detail] (2010), oil on canvas, 30 x 30 by Brian Shapiro Courtesy the artist](https://richardmcbee.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/10/Moses_on_Sinai-300x300.jpg)

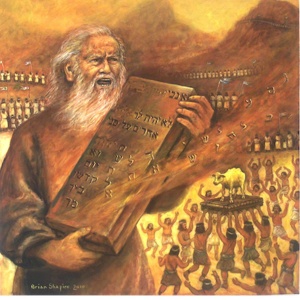

Apart from the detailed rendering of the sacred inscription, Shapiro’s painting is notable for the depiction of the vast Israelite camp far below Moses, giving us a dizzying perspective of being actually alongside Moses up on the mountain. Significantly this gives us a glimpse into the lawgiver’s personal experience; he is driven and transfixed by his awesome mission to meet the Almighty yet again.

The Sinai experience appears again in Moses and the Golden Calf, now depicting Moses’ reaction to that tragic sin. Here we are looking down at the Jewish people dancing around the golden statue while legions of Levites and women line the hills in the distance with their backs to the mob below, refusing to participate. As the Gemara describes that moment, the holy letters on the tablets flew off as Moses approached the sinful encampment and in anger smashed the tablets. While the midrash later tells us that God approved of Moses’ rash action, it is still deeply shocking for him to destroy such a precious gift from the Almighty. The expression on Moses’ face reflects his anger and pain, as if the letters are being ripped from his own flesh. In an amazing insight the artist has depicted Moses’ anguished reaction as if it were our own reaction of shock and dismay of such faithless behavior on the part of the Jewish people.

Finally the primordial staff appears again in Moses and the Rock, a painting of penetrating psychological insight. Moses, poised in the exact center of the painting, has just thrown the miraculous staff away in desperate terror. The blazing sun above and the orange-hued mountains in the haze of the desert heat all convey the frantic need for water the people must have felt. The cool green and turquoise water gushing from the barren rock convinces us of the magnitude of the ill-fated miracle. But it is the gesture and expression on his face that transforms the painting into a narrative of tragic personal failure for Moses. At this instant he has realized his disastrous mistake. In his anger at the Jewish people’s hysterical complaints about water he has struck the rock instead of speaking to the rock to bring forth water, as God had commanded him. He has just heard God condemn him to death in the desert just outside the Promised Land. His entire life’s work has been compromised, removing from him the satisfaction of leading his people into the Land of Israel. All because of anger.

This exhibition of Brian Shapiro’s recent midrashic paintings has revealed a fascinating aspect of Moses’ personality and narrative. Anger is a natural and necessary human emotion and yet the issue of anger management as it relates to our relationships with others is seldom explored in art or literature. Here in two significant paintings Shapiro investigates the consequences of Moses’ anger; at the Golden Calf Moses is vindicated only by the severity of the Jewish sin and yet at the Rock he has inadvertently failed to sanctify God’s holy name. Anger is clearly terribly dangerous as the Gemara states in Pesachim 66b; that “When a person becomes angry – if he is wise, his wisdom will depart; and if he is a prophet, his prophecy will leave him…” Shapiro has accomplished these insights utilizing the complex interactions between the basic Torah text and the rich descriptions of midrashic literature. But more importantly, it is the adoption of the midrashic methodology, its mindset of passionate investigation and creative imagination, which pushes these paintings to new heights of narrative insight.

Shapiro’s Midrash

Paintings from Midrash by Brian Shapiro

Chassidic Art Institute

375 Kingston Avenue, Brooklyn, New York