Rylands Haggadah: Medieval Jewish Art in Context

The Rylands Haggadah, created in Catalonia Spain sometime around 1330, is a towering masterpiece of Jewish Art. In addition to pages of piyutim surrounded by ornate decorative and figurative micrography, richly decorated Haggadah text and blessings, there is a 13 page miniature cycle depicting the Exodus story from Moses at the Burning Bush to the Crossing of the Red Sea.

This breathtaking work of art has not gone unnoticed. A full scale facsimile of the haggadah with a scholarly introduction and translation was published by Harry N. Abrams, Inc. in 1988, aspects of which were reviewed here on March, 2001. More recently the Rylands Haggadah was extensively compared to its “Brother” British Library Haggadah in Marc Michael Epstein’s The Medieval Haggadah (2011) as well as Katrin Kogman-Appel’s briefer investigation in Illuminated Haggadot from Medieval Spain (2006). Evidently one can even buy it as an iBook from iTunes. But most significantly for us, this diminutive gem is currently here in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art until September 30, 2012 as part of a series of loans of Hebrew manuscripts funded by the David Berg Foundation. It is not to be missed.

The Met’s presentation under the supervision of curators Barbara Boehm and Melanie Holcomb has made every effort to present the miniature narrative cycle to its full advantage; “turning the page” every 4 weeks for the duration of the show. It is extremely unusual to actually show so many pages of a rare manuscript, especially since the Rylands Haggadah is very rarely shown even at home and was specially restored for this loan. Of course inherent to the exhibition of a bound manuscript is the fact that all of the images can never be physically seen at one time. While this could have been rectified by a digital and/or printed display, the Met chose to place this manuscript in the somewhat constricted space of the Medieval galleries in the effort to show “Medieval Jewish Art in Context,” here within the Christian Middle Ages. Additionally all the exhibited pages are beautifully reproduced on the Met website. The Met has programed lectures and gallery talks to elucidate the complexities of the Rylands, the most notable of which was Marc Michael Epstein’s lecture on April 11, 2012, now available online (www.youtube.com/watch?v=jaoAOA5jQm0).

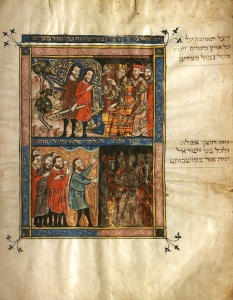

As of July 31st the miniature pages of the Plague of Locusts and Plague of Darkness will be facing the Death of the First Born and the Sack of Egyptian Treasures. Epstein comments that the Rylands Haggadah seems to express a somewhat “more literal attention to the text of scripture,” especially in relation to its model, the “Brother” British Library Haggadah. Overall the Rylands is more bloodthirsty toward the Egyptians with “more frogs, lice, wild beasts, and boils, more hideous grimacing on the part of the afflicted Egyptians; more suffering…” than its “Brother.” In the Plague of Locusts no less than 13 giant locusts swarm around Pharaoh and his advisors, one of whom grimaces in terror. Moses and Aaron are seen on the left side of the illumination calmly pointing to the destruction in the human realm (i.e. Pharaoh and his court) and how in the agricultural realm next to Aaron, i.e. Goshen, the vegetation was unaffected. So too in the panel directly below, the Plague of Darkness completely obscures the hapless wide-eyed Egyptians while the Israelites smile and point at their misfortune, basking in the bright light, even under a starlit sky.

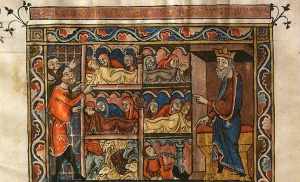

On the opposite page the terrible Death of the First Born is depicted in uncompromising brutality. In the middle six panels of dead Egyptians, each mourned by two women, along with dead animals and a chained prisoner, are framed by Pharaoh on the right and Moses and Aaron on the left. Pharaoh seems to point accusingly at the death of innocents along with convicted prisoners whereas Moses and Aaron respond by pointing directly to him (and his hard heart) as the cause of so much agony. Interestingly Epstein comments that the wretched state of the dead prisoner forces us to notice that while the Egyptians (stand-ins for contemporary medieval Christians) were wicked, nonetheless they, “were to be depicted in a properly gracious and graceful manner,” much in the same tone and style as the oppressed and downtrodden Jews. It would seem that neither side was demonized.

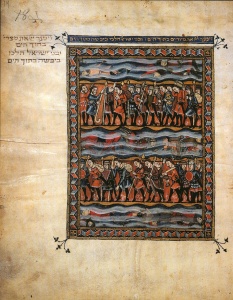

From August 28 until the end of the exhibition on September 30 the pages depicting the Israelites Leaving Egypt, Pharaoh’s Pursuing Army and the Crossing of the Red Sea will all be on view. The strident nature of the Rylands Haggadah is again seen in Leaving Egypt with the emphasis on “The Children of Israel were armed when they went up from the land of Egypt” (Exodus 13:18). With the exception of Moses, Aaron and one man with a kneading bowl, each of the 12 men is armed with a sword, pike (a very long thrusting spear) or halberd (a battle ax mounted on a pike). As Epstein observes, this is “a nation of warriors.” Just below Pharaoh’s Pursuing Army brings the narrative to a fever pitch with the mounted Egyptian soldiers (actually medieval knights) led by the Pharaoh right on the heels of the armed but fleeing Israelites. Moments later on the next page the entire army will be drowned.

The strident militancy continues in the opposite page depicting the Crossing of the Red Sea where, with the exception again of Moses, Aaron and perhaps 2 others, all 20 others are armed to the teeth, a “military Exodus” for sure. No women, children nor flocks, just an army marching forward while individuals point triumphantly at the three surrounding bands of Egyptian dead in the sea. Through the flowing waters we see them, eyes closed, some grimacing even in death, horses and arms sunken along with Pharaoh himself floating face up and his golden crown breaking through the right-hand ornamental border. It is an unabashed triumph for the Jewish people over the wicked Egyptians. And, considering that both in costume and mindset the Egyptians in this Haggadah represent contemporary Christians, clearly this is a Jewish Art that expresses the tension between Christian rulers and Jewish subjects in the difficult years of 14th century Spain.

While there is much to be said for all the images of the plagues displayed earlier this year (the exhibition opened March 27, 2012); the effective beginning of the narrative cycle, the Burning Bush and the Return to Egypt, demands special attention especially in the attempt to place medieval Jewish Art in context. The curators observe, “in medieval Europe, where art was prized as a means of storytelling, Jewish life and history were often represented visually.” To contextualize the Rylands Haggadah they have placed in adjacent cases examples of Jewish subjects found in Christian medieval art. One shows the Battle of the Maccabees, here prefiguring the Crusaders similarly fighting to save the Holy Land. Two illuminated Bibles are presented: one with an image of Judith beheading Holofernes, an episode dear to Jews but not found in our Tanach while the other features the martyrdom of Isaiah by being sawn in half. This episode is also non-textual but well known in both the Talmud (Yevamos 49b) and the Pseudepigrapha.

Another case features two illuminated leaves from the Postilla Litteralis of Nicholas of Lyra (1360-80). This extremely important and much copied biblical commentary attempts to harmonize Rashi’s commentary within a Christian perspective! The illuminations here show the arrangement of the various tribes encamped around the Tabernacle and the curtains of the Tabernacle itself. The Rylands’ image of the Return to Egypt presents another kind of surprising interaction with the surrounding Christian culture.

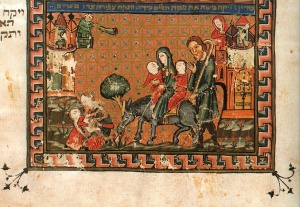

In the Book of Matthew, Joseph and Mary flee with their child Jesus to Egypt to escape King Herod’s attempt to murder a presumed child redeemer. Some scholars see this passage as a deliberate attempt to link the early history of Jesus with Moses the Redeemer, specifically the verses of the return to Egypt of Moses, Tziporah and their two sons seen in Exodus 4:20-26. The artist of the Rylands Haggadah (as well as the Golden Haggadah) seized upon this Christian appropriation of a Jewish text, in turn appropriating the Christian depiction to depict the original Jewish theme. The results are revelatory.

At the time of the creation of the Rylands Haggadah (ca. 1330) the visual motif of the Flight into Egypt had been well established and was ubiquitous. This subject depicts a female figure holding a child on a donkey, in profile, being led or followed by a male figure with a staff and is seen in major Italian works by Duccio (1311), Giotto (1306) and most notably a French Gothic illumination in the Book of Hours for Jeanne D’Evreaux (ca. 1320) currently in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Cloisters.

In our Rylands image (unfortunately damaged) we can see Tziporah on the donkey holding one child in front while her second child clings to her back. Moses is guiding them along from behind as they travel from Midian, depicted on the right, to Mitzraim depicted on the left. In the lower left we again see Tziporah, now on kneeling on the ground quickly circumcising their son Eliezer, understood by Rashi as her heroic act to save Moses’ life from Divine displeasure (see Nedarim 31b-32a).

Here the Rylands’ artist brilliantly contrasts the Jewish Return to Egypt, depicting the pivotal narratives of saving Moses’ life through of the mitzvah of circumcision and the very beginning of the redemption of the Jewish people, with an Christian anecdotal episode of the hasty fleeing of the “holy family” to Egypt that will only necessitate a return to take up the narrative again. He has appropriated and subverted a piece of Christian visual culture, one based on a Christian adoption of a Jewish text, and has asserted Jewish mastery and primacy over sacred text. One hopes that the new owner over 600 years ago of what is now known as the Rylands Haggadah appreciated what his humble craftsman delivered into his hands. I know we do.

[I am deeply indebted to Marc Michael Epstein’s The Medieval Haggadah, Art, Narrative & Religious Imagination (2011) for many insights into radical nature of these manuscripts.]

The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Fifth Avenue and 82nd Street, New York