Woodcarving from the Synagogue to the Carousel

Much like the Jewish people themselves the legacy of Jewish Art has miraculously survived seemingly endless assaults of the past two centuries. In Eastern Europe the forces of assimilation, cultural denial and holocaust have worked tirelessly to abandon, reject and destroy a vast portion of our cultural birthright. Countless synagogues, along with their prized carved arks, decorated walls, illuminated manuscripts, books, Judaica and folk art creations have been abandoned and left to rot as traditional communities have withered and died. Others have been purposefully destroyed outright by those who hate us. Nonetheless, a surviving remnant of this precious legacy has endured and one of the best examples of its glory is currently to be seen at Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses on exhibition at the Folk Art Museum. Both the exhibition and the brilliant catalogue are musts for all who cherish our cultural heritage.

Aside from pure artistic pride we will discover another historical gem in this exhibition; the echoes of a fantastic 17th century Baroque art as filtered through a Jewish consciousness embedded in its woodcarving, stone cutting and papercuts. The exhibition charts the art of Jewish craftsmen as they worked in stone, paper and wood from their origins in Eastern Europe to their subsequent works in American synagogues and the surprising role they played in the burgeoning carousel industry in the early 20th century.

Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses is divided into five chronological sections starting with photographs and exacting models of Polish, Ukrainian and Lithuanian wooden synagogues. This introduction sets a tone of architectural and visual opulence more common to 17th & 18th century Baroque Italian churches than our subdued and austere concept of synagogue architecture and interiors. What we forget (and these photographs confirm) is that the excitement and passion of the Baroque, emblematic of the Counter Reformation assault against the Protestant heresy, became a universal visual language for all of Europe, including the Jews, in the early years of the 17th century. While the Renaissance stressed balance and harmony, the Baroque style was exuberant, dramatic and emotional, reveling in fantastic animals and symbols that would express a fervent religious experience.

The salient features of these synagogues were the lavishly painted and decorated interiors and the elaborately carved wooden arks. From these surviving photographs we can make out but a few examples of a flourishing art form: ornately detailed floral designs interspersed with zodiac and panels of textural quotes (Chodorow, Ukraine) and a wonderful painted menagerie of winged lions, eagles and fantastic beasts (Grojec, Poland) that adorn the sacred interiors.

The 18th century Torah ark seen from Olkienniki, Lithuania is a masterpiece of iconography, intricately carved and crowned with a double headed eagle (representing temporal and celestial power) grasping a shofar and lulav bundle. Below are the ubiquitous blessing of priestly hands that hovers over a crowned set of Tablets of the Law flanked by carved griffins, unicorns and mythical animals. Even closer to the viewer is a depiction of the Ouroburos, a serpent swallowing its own tail that represents the Leviathan, emblematic of renewal, eternity, redemption and the source of nourishment in the messianic world to come. Arks like these were often over 30 feet tall and were Baroque masterpieces of wood carving that substitute squirming beasts and vine-like flowers for the flying angels so common in many churches. Of the hundreds of similar wooden synagogues, almost all were destroyed in the Holocaust. All that is left are a dozen or so photographs, many of which we see here.

The next section of photographs are carved gravestones from Eastern Europe that continues the rich iconography in a decidedly more primitive form. The four animals from Pirke Avot 5:23, “ Be bold as a leopard, light as an eagle, swift an a deer and strong as a lion to do the will of your Father in heaven,” are still in evidence as well as the messianic imagery of the Ouroburos and the ever present lions that guard the precious Torah. The difference is that almost all the renderings in stone are considerably more iconic than the more pliable wooden arks. These rich and inventive images are trapped in a tenacious medium and ultimately archaic representation. Only the inherent durability of stone and pure chance has allowed many of these tombstones to survive the ravages of time and war.

Papercuts are ultimately the most surprising aspect of this exhibition, presenting 32 brilliant masterpieces in a tour de force of folk art skill. Their creativity and diversity are breathtaking and this showing amounts to a world class introduction to this uniquely Jewish art form. This delicate and demanding art was practiced primarily by young boys and men starting in the nineteenth century when paper became relatively inexpensive. The paper was folded, cut according to an exacting design and then laid on solid colored background to enhance the image. Some, if not all, of the paper was ornamented with pen, ink and watercolor to create a rich, delicate and multilayered symmetrical image. Almost half of the papercuts shown here are American with the rest from Eastern Europe. The subjects range from omer calendar, zodiac, succah decoration, mizrah (the majority of examples containing the phrase mi tzad ruach hayim; “From this direction comes the breath of life”), amulets, shiviti, yarhtzeit, family memorials and an eruv tavshlin. The richness and complexity of the imagery is breathtaking, one example simply more stunning than the next. The very nature of the detailed and painstaking medium becomes the message of an intense visual universe brimming with symbols and shared meaning.

One especially unusual example of a mizrah is by Natan Moshe Brilliant from Lithuania (1877) that manages to combine not only cut and painted elements but also collages from printed sources thereby weaving a symbolic and complex narrative. Starting at the bottom, Moshe and Aaron flank a menorah within an evocative architectural space supporting a register of zodiac images that in turn is the foundation for depictions of David playing the harp, Abraham slaughtering the ram, Moses removing his shoes at the Burning Bush and finally a poetic rendering of Noah and the ark. And this only scratches the surface of the iconographic treasure house that is contained in this large papercut masterpiece.

Just as with the tombstone carvings, the difficulty of the medium itself tends to limit the depth of content available to the craftsman. Complexity made up of stock symbols can only take artistic expression so far. The great flowering of artistic expression is to be found in the Torah ark woodcarvings in the next section.

This selection of 32 rampant lions, some with luchos (Decalogue), is the most exciting visual and artistic aspect of Synagogue to Carousel. While two actual arks are shown (one from Nova Scotia, Canada and the other from Chelsea, Massachusetts), all the rest of these works are extremely evocative fragments of ark wood carving; the ever present lions flanking a depiction of the frequently crowned 10 Commandments. As we see these examples of Torah arks made in America we recognize that the Baroque elements have been sharply reduced to only a few elements; peripheral ornamentation and the depictions of the rampant lions. In these lions the profiles are more schematic and standardized ferocious beasts. But once they face us a wonderful transformation takes place. The animal face takes on more and more human qualities, rendering the symbolic guardians of the Torah considerably more complex and nuanced. It is here that the artistic genius and genuine passion of these mostly anonymous craftsmen soars.

Three sets of lions on one wall offer instructive distinctions. One, from Newport, Kentucky presents solemn, serious, Egyptian-like animals; another pair from Kansas City, Missouri bellows a hysterical unhinged growl with tongues protruding, and finally a Midwestern pair guards with a set of profiles reminiscent of Chinese images; blood red eyes, mouth and claws. The diversity of images seems to represent the individuality of both artist and the congregation in terms of what guarding the Torah might mean.

Three pairs of lions (possibly created by the same artist) and salvaged from the Lower East Side seem gleeful in their defense of the holy luchos. Another set of rampant lion faces (also from the Lower East Side) remind one of the terribly serious and fearsome elders of those venerable congregations, weathered faces that betray the trials and tribulations these immigrant Jews endured. What comes to mind perusing these sculptures is that each represents a destroyed Torah ark and an abandoned congregation. These are the surviving fragments of the decimation of American Jewish life, their beauty and diversity are the tragic evidence of how much has been lost.

The artisans who labored on the American Torah arks were immigrants from Eastern Europe who practiced the same skills back in Europe. But once here in America they began to diversify by necessity, many using their skills in furniture, cabinetmaking, woodworking and carpentry. When they could they continued in creating Torah arks such as the legendary Samuel Katz from the Ukraine. He arrived in America in 1907 and by 1913 had moved to the Boston area. During the 1920’s and 1930’s he carved at least 23 Torah arks making him the “most prolific identified ark builder in America.” But not all such artisans were as successful.

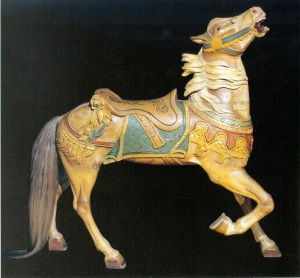

America at the turn of the 20th century was a land of opportunity and the combination of an immigrant urban population, mass transit and the greatest amusement park in the United States; Coney Island, opened doors for Jewish craftsmen to work in what was a booming industry; the carving of horses and other animals for carousels and other amusements. As the exhibition shows, three Jewish carvers, Marcus Charles Illions (whom we know did synagogue carving), Solomon Stein, Harry Goldstein and Charles Carmel, brought to perfection was became known as the Coney Island Style of animal carving. It is characterized by flamboyant and expressive details and poses of the horses. Manes flew in the air, horses tossed their heads, stomped their hoofs and snorted in unbridled passion.

From the examples we have here these artists had clearly different styles. Illions’ animals tended to have a fluid Baroque quality, combining a forceful naturalism with drama. In contrast Stein and Goldstein (they were a partnership) tended towards a more restrained and medieval image. Finally Carmel, while fluent in more than one style as they all were, seems to favor the brute passion of a barely tamed beast characterized by an open mouth, lolling tongue and terrified eyes. It is in his works most of all that the Baroque heritage surfaces in its secular manifestation and is most deeply felt.

The history of the American synagogue since mid-century has been tragic, many, many abandoned and destroyed along with the precious art they contained. So too the great centers of carousel and amusement park carving, abandoned and/or updated to machine made imitations. The guest curator of this exhibition, Murray Zimiles researched and documented this vast project for the last 20 years, tirelessly collecting material and connections from Europe, America and Israel. Stacy C. Hollander, the American Folk Art Museum senior curator coordinated with Zimiles and made this exhibition possible. Together they have “return[ed] to the Jewish people, and to world culture, an awareness of and appreciation for a visual tradition of great beauty, vitality, symbolic richness, and decorative complexity that flourished over a period of several centuries in Central and Eastern Europe and flourished briefly in the New World where it underwent a remarkable transformation and secularization.”

The remnants we see here are indicative of what we as a people, as Jews, are capable of creating. We only have to believe once again in our skills and insights as Jewish artists to allow our art to bloom once again. It is this that makes Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses such an inspirational exhibition.

Gilded Lions and Jeweled Horses: The Synagogue to the Carousel

American Folk Art Museum

45 West 53rd Street

New York, N.Y.

www.folkartmuseum.org