Mourning, Memory & Art

David Roberts (1796-1864) was a Scottish painter who in the late 1830’s traveled extensively in the Levant and Egypt documenting “Orientalist” sites in drawings and watercolors. Together with the lithographer Louis Haghe, he marketed his work to a public eager for exotic scenes. Queen Victoria was one of his first customers.

Roberts is not the only artist to memorialize visually the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., an event marked, along with the loss of the First Temple four centuries earlier, on the ninth of the Hebrew month of Av (Tisha b’Av). On this day, which this year falls on August 9, Jews are commanded to mourn their ancient tragedies by fasting, reading the biblical book of Lamentations, and reciting dirges.

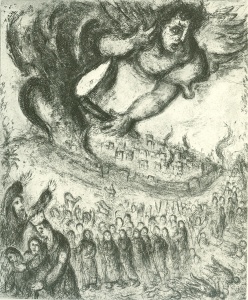

In order properly to mourn, one must feel the tangible loss of something cherished and remembered. Words alone are insufficient for the task: it helps enormously to be able to visualize, if only in the mind’s eye, that which has been lost. Among Jewish artists, two who have notably attempted to deal with the events are Marc Chagall and Archie Rand. Chagall’s Capture of Jerusalem, from his 1956 series of etchings drawn from the Bible, cuts to the chase, presenting an anguished angel setting fire to Jerusalem as the Jewish people flee. The artist’s insight is unnerving, as if imploring God to answer why such terrible destruction had to be wreaked on His house and His people.

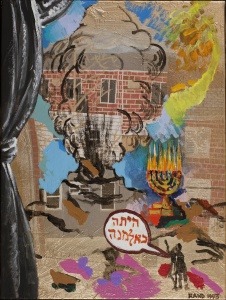

Rand, in Av (1993), depicts the prophet Jeremiah exclaiming (in the words of Lamentations) that Jerusalem has “become like a widow”: with a dark curtain pulled back, we see the smoldering ruin, fractured with after-images of a grand building devastated and shattered. The painting may not provoke tears of mourning, but it, too, poignantly raises the question of God’s justice.

Other contemporary Jewish examples are few and far between, perhaps because of the hesitancy with which many Jewish artists approach biblical themes and the overwhelming preoccupation with the Holocaust as the tragedy of our own time. The pickings among non-Jewish artists are similarly slim, but grow marginally more plentiful if we go back in time.

The French classicist Nicholas Poussin (1594-1665), passionately obsessed with antiquity, delivered a convincing expression of chaotic carnage in his Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem (1638). We are in the thick of battle. Dead and decapitated bodies litter the Temple courtyard, and captives are being hauled off or summarily executed. The Roman commander (soon to become emperor) Titus, on a rearing white steed, is thunderstruck by something he sees high above the Temple; many of his men are similarly transfixed by the mysterious sight beyond the upper edge of the canvas.

In Western depictions of the destruction, this may be the first time the awesome hand of God is acknowledged in the events. Unlike the Arch of Titus in Rome, about which more below, Poussin goes well beyond the defeat of the Jews—indeed, there is nothing Jewish about the defeated—to address God’s role in history.

The 19th century offered more visions steeped in theology by non-Jewish artists. Wilhelm van Kaulbach’s enormous Destruction of Jerusalem by Titus (1850) features the prophets Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and Daniel overseeing the high priest committing suicide as his people are being slaughtered. The mythical “Wandering Jew” is driven off the scene, hounded by demons, while on the right, sweetly painted Christians turn their backs on the whole horrific affair. Kaulbach means to testify to the end of the legitimacy of the Jewish people.

Then there is Francesco Hayez, an Italian Romantic given to allegorical paintings and portraits. In his The Destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem (1867), a bloody riot is taking place on the gigantic stone altar in the Temple courtyard. While Hayez doesn’t get the orientation of the altar correctly, or the fact that it had a ramp rather than steps, the chaos and mayhem are overwhelming, and rendered even more so by the invaders’ capture of the golden menorah. Amid the billowing smoke we see angels fleeing: a nod to the idea that in the course of this event the divine presence fled from the Temple Mount. In spite of its chaotic splendor, however, the painting never rises above a costumed tableau vivant.

Which brings us back to David Roberts. In his The Destruction of Jerusalem, a breathtaking panorama unfolds before us: the Temple Mount, the city to the west, the Antonia fortress, the whole operatic spectacle seen from high up on the Mount of Olives. The north wall of the city is in flames, while in the foreground a Roman legion of archers is launching an (improbable) attack from high over the Kidron valley. Bare-breasted female captives hysterically bemoan their fate, for the most part ignored by the soldiers.

Roberts’s scene, like so many of the others, is grand but finally unmoving: a dispassionate drama from antiquity, in this case lacking even a hint of the theological element captured by Poussin, Kaulbach, and Hayez, not to mention Chagall and Rand.

Curiously, the only depiction of the destruction that really does bring tears to the mourner’s eyes is the oldest and the cruelest. The Arch of Titus was erected in the Roman forum a mere twelve years after the victory over the Jews in Jerusalem. As part of Roman pagan ritual, a procession through the arch by the conquering general would bring blessing on the city of Rome and purify the returning soldiers. The reliefs on the inside of the arch depict the triumphant commander opposite the spoils taken from the Temple—among them, the massive golden menorah carried by twelve men, the showbread table, and two silver trumpets.

Even in its present condition, battered by two millennia of standing in the open air, the scene has the impact of a news photo taken yesterday. More than words, more than imagined re-creations on canvas, a confrontation with this heartrending contemporaneous image brings home the power and the pain of crushing defeat. This—the concrete, palpable tokens of Jewish sovereignty and faith, right there in front of us in the capital of the pagan victor—is what was lost, and must never be lost again.