A Movie by Jean-Marie Straub & Daniele Huillet (1975)

How can the artist presume to make art when every stroke, every effort at creating an intelligible and beautiful object, might be construed as an affront to the wholeness and perfection of God and His handiwork. Every one of the artist’s images could be seen as a potential idol, a potential Golden Calf. This is the dilemma embodied in the conflict between Moses and his brother Aaron that Arnold Schoenberg examines in his 1932 opera Moses und Aron. And it is a central theme explored in the 1975 film Moses und Aron by the radical filmmakers Straub and Huillet. The screening on Sunday January 25 of the New York City Opera’s Cinematic Opera / Operatic Cinema series effectively reintroduced Moses und Aron to New York audiences in advance of the release of the CD by New Yorker Films.

The Straub/Huillet film is a stark and yet accurate rendition of the opera (reviewed here on February 13, 2004 and available at jewishpress.com) that radicalizes the already controversial themes found in the original. Known for their austere films with ostensible Marxist overtones Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet are well-known cinematic collaborators who created at least 26 films between 1968 and 2006. Their signature technique involves long immobile shots and the use of gritty locations along with non-professional actors and actresses. For Moses und Aron they selected an ancient Roman amphitheater in Alba Fucens in the Abruzzo region of Italy, half way between Rome and the Adriatic. The weathered ruins provided a perfect setting for the unfolding drama of a very peculiar kind of brotherly rivalry, each representing a different approach to the revelation at Sinai.

It becomes increasingly obvious as the film unfolds that the brothers, Gunter Reich as Moses and Louis Devors as Aaron, are dramatically different; the character of Moses embodies the distant prophet enraptured with an abstract idea; a fundamentalist, a radical monotheist. In contrast Aaron is the popularizer, smooth-talking emissary to the rambunctious Jewish people, a confident creator of artifice, a salesman of the monotheistic idea.

The filmmakers explained their methodology in a 1976 interview with Joel Rogers (Jump Cut – No. 12/13 pg.61-64) stating that after seeing the opera in 1959 they realized that “the staged opera was not at all what Schoenberg had imagined. Not what he planned.” Rather his intentions were “to provoke and rally the audience. Such a work in 1930 or 1932 was an incredible provocation.” Certainly taken at face value the text of the libretto (written by Schoenberg) and the ultra modern 12 tone scale of the music was provocative to any potential audience in conservative and anti-Semitic Vienna at the dawn of Hitler’s election in Germany. However, whether Schoenberg was intent on revolution is far from certain. In any event Straub and Huillet use this interpretation to exacerbate the antagonism between Moses and Aaron. The opera as normally performed ends with the second act and Moses bemoaning, “Unrepresentable God!… Shall Aaron, my mouth, fashion this image?… Thus am I defeated!…” The filmmakers see this as “the defeat of Moses, the defeat of the progressive idea…” Therefore the film shows the fragmentary third act, never performed in New York before, without music (as Schoenberg had left it) in which Moses is triumphant over Aaron. Aaron is seen bound with Moses standing over him, accusing his brother that “images lead and rule this people…you have betrayed God to the gods, the idea to images, this Chosen People to others…”

In his comments at the New York screening David Levin, Associate Professor at the University of Chicago and executive editor of Opera Quarterly, sees this opera and especially the film as being uniquely non-operatic and non-cinematic. Central to most performance and film are the notions of spectacle, entertainment and visual and auditory pleasure. These elements are suppressed in the opera (Schoenberg’s 12 tone scale music being particularly demanding while the highly intellectual theme daunting at best) and in the film almost obliterated.

Rather what we have in both is an expression of high modernism, rigorous in form and distant from popular culture if not most audiences. Clearly the film makes explicit what is implicit in the opera.

The film opens with a shot of the back of Moses’ head, seen slightly from above. He begins his sung-speech dialogue with the Voice from the burning bush. That shot remains static for close to eight minutes until interrupted for another minute by a black screen, with music, that announces the second scene. Then a sung and sung-speech visually static dialogue commences with Aaron for another eight minutes, and so on through the 12 scenes of Act One. The costumes are banal and regrettably “bible movie”–Arab style robes. The chorus are similarly dressed, stiffly lined up in a small group, delivering their deadpan reactions to the at first unwelcome news of a new God. No one enters or exits, no one moves. The camera in panning between an isolated individual and the chorus or between individuals is the active eye. This highly static and stylized cinematography shot against colorless ruins in a oval amphitheater has the curious effect of making the music seems more intense and colorful that I have ever heard it. And of course the lack of visual excitement concentrates the meaning in the sung dialogue.

In the fourth scene the people demand to see God to worship Him. They are told “Shut your eyes and close your ears… only then can you see Him!” The awesome starkness of Straub and Huillet’s movie reflects and radicalizes Schoenberg’s vision of the invisible, incomprehensible God. While uncomfortable and at first tiring, their compelling vision perfectly fuses the abstract concept of the unseeable, unknowable God with a cinematic form that is almost totally visually static, dry and barren… almost not there at all.

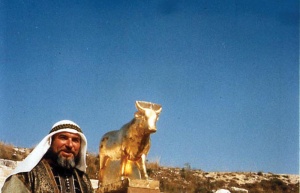

The second act begins with “Before the Mountain of Revelation” and immediately something has changed. “Where is Moses” the people demand as they ferment rebellion. Aaron tells them, “You shall provide the stuff, I shall give it a form… imaged in gold forever… You then shall be happy!” And Aaron makes the enormous Golden Calf. Suddenly five slaughters dance before it, choreographed as a rather predictable modern dance. Nothing is static. Abruptly there is movement, drama, naturalistic images that devolve into a staged formulistic orgy. The images morph into the night with all manner of terror and excess, sacrifice, violence and blood offerings. Because the movie has totally changed its tone and style we are convinced that Aaron, in trying to appease the unbelieving people, has unleashed the forces of the mundane, the natural, the physical and the banal.

Moses returns and accuses Aaron… “What have you done?” Aaron shockingly answers, “Nothing unusual…” Aaron argues for the people, their needs and his love for them while Moses declares “for the idea! My love is for my idea, I live just for it.” We have returned to the static, the ideal, the sacred idea. Moses smashes the tablets he carries declaring, “they are images too!” He accuses Aaron that even the fiery pillar and the pillar of cloud are images… “Godless image!” And with that Moses sinks to his knees and declares he is defeated. But of course the movie takes us to the third act where Moses triumphs over all images and his brother is utterly defeated.

Straub and Huillet presents in Moses und Aron an unbearable image. Their work posits an elemental struggle, an idiosyncratic history of our beginnings with an imageless God, imagining, much like Schoenberg and yet more fierce and unforgiving, what the experience at Sinai must have been like for the Jewish people and their leaders, brothers deeply divided.

These beginnings help us understand our rebellion and stumbling in the wilderness. Only after forty years did we slowly begin to understand. And we used, much like Aaron, images. We fashioned a tabernacle for the ineffable “to dwell in.” We learned His laws and commands to please Him, we in fact created images, at least mental images, even definitions, of the unknowable Divine. And from this experience we learned (and were commanded by God Himself), that the idea of a radical monotheism could not nurture a people and that the creator of artifice, ritual, even art would help feed our spiritual lifeblood for generations to come.

So the Jewish artist can make art and will not offend God. Part and parcel of God’s creation is human creativity. Creator and created are secure. Schoenberg and his film makers Straub and Huillet in their re-reading of the biblical text take us back to a time at Sinai when it wasn’t so clear.

Moses und Aron

In German with English subtitles

New Yorker Films