Retrospective At Yeshiva University Museum: Moritz Daniel Oppenheim

Many of these paintings I do not like. Some I do. All of them are very important for us to look at and understand since Oppenheim’s work represents the seminal encounter between Jewish tradition and the challenges of the modern world.

This exhibition, Moritz Daniel Oppenheim: Jewish Identity in Nineteenth Century Art, presents over 90 paintings of the first and perhaps most famous Jewish artist of the 19th century. It presents all aspects of his very successful career and for the first time shows his depth and skill as a portraitist and as a genre painter. The exhibition at Yeshiva University Museum on 16th Street is beautifully hung and designed by Oliver Hirsch of Hirsch & Associates Fine Art Services. The show was organized by the Judisches Museum der Stadt Frankfurt am Main under the patronage of the German Chancellor Gerhard Schroder and is accompanied by a definitive catalogue raisonne published by the Frankfurt Jewish Museum. It must be seen by anyone interested in Jewish Art.

Who is this man Moritz Oppenheim (1800-1882)? He was the first Jewish painter of the 19th century to work within the German non-Jewish world and still affirm his Jewishness. As far as we know he remained observant and was within the community of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch in Frankfurt, Germany.

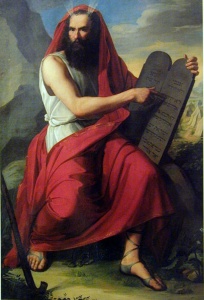

He was eighteen when he painted the aggressive Moses with the Law. It is a wall sized evocation of our Teacher pointing at “You shall have no other gods…” within the Ten Commandments, that maintains respect and piety in both the powerful depiction of Moses and the avoidance of using God’s name fully spelled out. The emphasis on the second commandment by the artist shows a subtlety well beyond his years.

His work as a portraitist of prominent gentiles and Jews was the work that gained him well-deserved universal celebration. Throughout his career, his portraits are convincing encounters with real people. Both the serious and evocative 1822 Self-Portrait and Ludwig Borne (1831), of the apostate journalist and poet who worked for Jewish emancipation, show Oppenheim as a master of romantic brushwork and direct observation. His portraits of the elder Hanna Baer and Joseph Baer, both from 1840, have a dignity and simplicity of the Golden Age of Dutch portraits.

The more complex paintings he did of members of the Rothschild family over a twenty year period rise above simply competent society portraits. His bridegroom portrait of Lionel Nathan von Rothschild (1836) exudes a confidence in which all things seem possible. Oppenheim seems to genuinely share the optimism of his sitter posed in a classic triangular composition in perfect balance before a subdued and stately landscape. The painting celebrating the marriage of Charlotte von Rothschild to her cousin Lionel is a much more studied affair that attempts an early Renaissance style. Oppenheim is always a stronger painter when he is simpler. The masterful portrait of Adolph Carl von Rothschild (1851) is a tour de force about power, privilege and wealth. Simple, direct and regal, the painting has an empathic quality that tells us that Oppenheim saw his own success and fate bound up with these very successful fellow Jews.

And rightfully so since he had been a successful portrait painter since his twenties, winning competitions, and finally meeting the leading figure of German culture, Goethe, and illustrating his works. He was commissioned to paint the portraits of Kaiser Otto IV and Joseph II in 1839 and was finally granted a prized citizenship of Frankfurt in 1852, quite an accomplishment for a Jew in those times.

His humble origins in the ghetto of Hanau, Germany were most prominently explored in the genre work he did in the last twenty years of his life. The extensive series, Scenes from Traditional Jewish Family Life, seen here in three original oil paintings and a seven grisailles (painted in gray to accommodate mass reproduction) documents for the first time German Jewish family life cycle events. The series is presaged by Oppenheim’s purported masterpiece, Return of the Jewish Volunteer from the Wars to his Family still Living in Accordance with Old Customs (1834). This painting is the first of the Jewish family life series and it shares with the later series many of their problems and difficulties.

Many of these works exhibits obsession with detail, sentimentally exaggerated gestures, and rolling eyes typical of theatrical moral parables. They are illustrations of set themes such as the values of hearth, family and country or superficial piety. They illustrate the Jewish yearly events in a literal description of each event. Objects tend to be arranged as isolated things (or predetermined symbols) rather than composed into meaningful relationships with one another. These paintings do not evoke by pictorial metaphors the complexities of the human relationships rather they remind one of silent movie stills where exaggerated gestures, caught in mid-action, attempt to replace actual speech. As a result, most of the power, honesty and insight he exhibited in his portraits is lost or obscured.

At the same time these paintings are enormously important to understand in their social context. They reflect the efforts of Oppenheim to address and solve the dilemma that German Jews found themselves in the mid 19th century. The struggle to maintain a Jewish identity, whether as observant Jews or not, was constantly challenged by the powerful forces of assimilation and nationalism. The pressure to demonstrate that they were good and upstanding members of the growing German nation was overwhelming. Many Jews were unable to resist and converted to Christianity. Oppenheim, in this series of paintings depicting idealized late 18th century Jewish life in the ghetto argues for a pride in the collective Jewish past and the possibility of a Jewish future as an integral part of the German world. The

overt sentimentality of these paintings reflects the gnawing fact that the sureties of the past were gone forever and had been replaced by a modern reality that constantly challenged their faith and values.

Both The Wedding (1861) and The Rabbi’s Blessing (1871) are exceptions to the bane of illustration that mars the later work. They are self-assured, composed and allow the color and light to narrate their themes. The Wedding, with its golden glow and Venetian color, is especially impressive as an exotic 19th century Romantic view into another world.

Moritz Oppenheim confronted with his art a world with enormous parallels to our own. He knew how important it was to remain within the folds of the observant community even as he achieved great success beyond. His struggle to guide his fellow Jews is a fitting model for any Jewish artist working today. I would only hope that artists today would attempt to forge a future rather than simply confirm a past.

Yeshiva University Museum – Center for Jewish History

West 16th Street , New York, N.Y.