Modern Art / Sacred Space

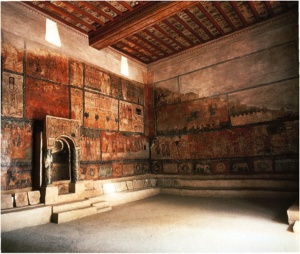

From the earliest synagogues preserved to the present, Jews have struggled with the role of art in their sacred spaces. Decorative or contemplative, subservient to architecture or an independent aesthetic experience? The Dura Europos murals (235 CE) and many early mosaic floors from 250 CE to 500 CE point to a dominant role of artwork brimming with biblical narratives and Jewish symbols.

Hundreds of years later, from the late Renaissance to the 20th century, almost all of the surviving European synagogues point to a much more subservient role, heavy on decoration and symbolism with almost no pure art. After the Holocaust many Jewish communities used modernist architects to build new sacred spaces often attempting to use art yet again as a meaningful component to interior design. Perhaps one of the most successful partnerships between modern architecture and modern art is the Chagall chapel at Hadassah University Medical Center in Ein Kerem (1962). Chagall’s masterful stained glass windows totally surround and dominate the sanctuary and yet since they are well above the heads of the congregation allow the synagogue space to be used without distraction.

Some fifteen years earlier Percival Goodman (1904-1989), an architect and urban planner, became convinced that modern architecture was essential in creating new post-war synagogues, firmly rejecting the historical styles that dominated synagogue design for the previous 150 years. Variously called the “leading theorist” of modern synagogue design (Phillip Nobel, 2001) and “the most prolific architect in Jewish history” (Michael Z. Wise, 2001), he designed more than 50 American synagogues, many in the suburbs where much new construction occurred since 1950. His works are characterized by simple functionalist design utilizing natural light and simple materials to evoke the modern and progressive ideology of his clients, mainly Reform and Conservative congregations.

His design for Congregation B’nai Israel in Millburn, New Jersey (1951) was a radical departure from normative practice. With the advice of art dealer Samuel Kootz, an early champion of Modernism and Abstract Expressionism, he invited three avant-garde artists to design artworks for this synagogue, thereby creating a thoroughly modern model for 20th century synagogues. He chose Adolph Gottlieb, Robert Motherwell and Herbert Ferber, all interested in spirituality, mysticism and symbolism, to design a Torah curtain, a mural and an outdoor sculpture. Due to a fortuitous renovation of the original building, all of these works are now shown in the current Jewish Museum show, Modern Art, Sacred Space: Motherwell, Ferber and Gottlieb.

Adolph Gottlieb was the oldest at 48 and perhaps the most mature. Already well known within the nascent Abstract Expressionist movement his interests in Jung, non-Western symbols and grid-based pictographic paintings allowed him to easily integrate his own Jewish background into symbols that resonated deeply with the congregation.

Gottlieb’s Torah Curtain is the focal point of the sanctuary creating a rich ingredient in Goodman’s design, towering almost 20 feet over the congregation as it reaches the full height of the main hall and luxuriates in the beautiful natural light of the clerestory windows. The red velvet, appliqué and embroidered tapestry was executed by the women of the congregation under the direction of Gottlieb’s wife, Esther. His abstractions place symbols of the Temple across the entire surface contained within his structured grid and freely mingle with equally obscure evocations of the 12 Tribes, the Lion of Judah, the Tablets of the Law and the Tree of Life. Viewing his preliminary sketches we can see how initially a lion figured prominently and after much reworking was finally reduced to a mere paw print, an artistic means of transforming a much too obvious symbol into a more subtle suggestion of royal power. Gottlieb’s Torah curtain perfectly resonates with the simple elemental forms of Goodman’s fundamental design.

Robert Motherwell’s massive mural (approx. 6’ x 15’), placed in a somewhat cramped entranceway to the classroom area, unfortunately is not as persuasive. As the only non-Jewish artist he was tutored by art historian Meyer Schapiro in Jewish themes and symbols and, considering his background in philosophy and as modernist spokesman, he was extremely receptive to these ideas. The final painting is ultimately more of pastiche than a synthesis of ideas. The Tablets of the Law and the Menorah are clearly recognizable. His preparatory sketches shown here all have more life and energy than the final product. They demonstrate the rough edges and passion of classic Motherwell works. For an Abstract Expressionist one would hope for more expressionism in paint handling and surface than is seen in the mural itself. It is as if he was overly cautious to get the “Jewish stuff’ right, making sure it wasn’t too abstract.

Herbert Ferber’s And the Bush Was Not Consumed was conceived in collaboration with Rabbi Max Gruenwald of B’nai Israel, an ardent supporter of the new synagogue design. Thereafter the sculpture’s progress was monitored by him and the architect. Ferber worked on many sketches and small models before he offered to enlarge the lead-coated copper work to its current epic proportions of 12’ high by 8’ wide, fittingly mounted on the building façade forming the back of the Torah ark that was covered by Gottlieb’s Torah curtain. The artworks of course could not be seen simultaneously but the architectural concept was nonetheless thrilling.

Ferber’s angular and curvilinear forms are unfortunately neither evocative of a Divine presence in the Burning Bush (long the symbol of the Conservative movement) nor of the metaphorical resilience of the Jewish people. Seeing the work up close does not yield an evocative surface and the calligraphic shoots fail to coalesce into a coherent composition. His work is ill served by its placement on the north façade, making it frequently hard to see in shadow and is further hampered from observation by its distance from pedestrian access. While it was surely daringly abstract in 1951, it is less than exciting today.

The curator Karen Levitov has accomplished something very special by bringing these works into such close proximately (which is not possible in their original setting); simultaneously placing them in the context of Goodman’s overall design and situating them in their historical context. She sees Goodman’s design and his use of avant-garde artists as a seizing upon a Utopian moment, forging a new and hopeful future for an American Jewish congregation. For Goodman the Holocaust had ignited his interest in a uniquely Jewish architecture as a means of securing the future of the Jewish people. New middle class suburban Jewish communities were optimistic about their future and seemed more than willing to embrace the progressive ideals of modernist architecture and art. Conversations with congregants and their children revealed that the artwork, its modern design and context, was much appreciated as an exciting element in their synagogue experience. Congregation B’nai Israel was on the cutting edge and the congregation was proud of that fact.

The concept hammered together by Percival Goodman was a resounding success with the congregation and ultimately yielded many other designs that thrilled other congregations for decades. Therefore why are some of these individual artworks somehow lacking, less than thrilling as radical art?

The complexities of abstraction and symbolism, form and function, begin to address the issue of art in a sacred space. Art in a sacred space must necessarily be subservient to the function of the space, i.e. religious ritual and contemplation. This concept, when art becomes essentially decorative, prevails when the artist knows and believes less than the dominant practice of the sacred space. But when the artist arrives with a concept and belief that can dominate the sacred space, then a work of art can begin to define the space both religiously and aesthetically.

This concept is evident in many of the masterpieces of Western art from the Scrovegni Chapel of Giotto in Padua, Michelangelo’s Sistine in Rome to Chagall’s windows in Jerusalem. The artist’s vision dominates by the pure force of his conviction, knowledge and belief. The sacred space is forced to accommodate a new religious vision. In the Millburn synagogue the opposite was true. Here Goodman’s vision of a modern Judaism reborn was paramount and the artists he chose were at best willing accomplices to his radical idea. Gottlieb seemed best poised to incorporate his Jewish background into his art while both Motherwell and Ferber ultimately approached the Jewish subjects as outsiders.

The role of art within synagogue architecture is complicated at best. When purely decorative it plays a subservient role and is almost always less interesting as pure art. When it presents a clear and persuasive religious vision it can oppressively dominate its environment. Percival Goodman’s Millburn synagogue reinvigorated the struggle to find the right balance to create a vibrant dialogue between artwork and the architect’s vision. It is a synthesis waiting to be born and when that balance is struck the results are electrifying both religiously and aesthetically. It is the sacred space we all pray for.

Modern Art / Sacred Space

The Jewish Museum

1109 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.

www.thejewishmuseum.org