Waters of Contention

The Mikveh Project: Photographs by Janice Rubin, Text by Leah Lax

For many modern Jewish women there is no more contentious image than the waters of the mikveh. The “ritual bath” is fraught with notions of uncleanliness, impurity and inferiority that traditional male dominated Judaism has imposed upon Jewish women. The curse cast upon menstrual blood is seen as a primitive and punitive denigration of the female body.

Two recent exhibitions of photographs at the Hebrew Union College Museum map possible navigations of the modern Jewish encounter with the feminine. Leonard Nimoy’s Shekhina (2002) proposes an erotic potential in feminine spirituality while The Mikveh Project by photographer Janice Rubin and author Leah Lax (2004) explores the healing nature of the mikveh for Jewish women. The contrasts could not be greater.

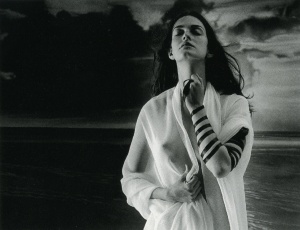

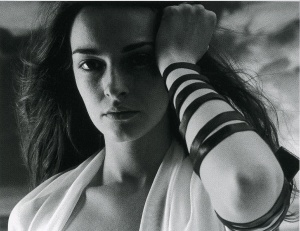

Nimoy imagines that his series of nude or diaphanously clad models are in some way “the photographic image of the invisible,” meaning a metaphorical approximation of the feminine Divine presence. The “inner light of spirituality” is depicted by theatrical lighting under gauzy drapery and banal cloud backgrounds. Some of the images utilize a tallis or arm tefillin strapped on a partially nude model in a feeble attempt to appropriate predominately male symbols of Judaism for feminine spirituality. Inherent sexuality, present in ample details of breasts, thighs and erect nipples, overwhelms his images that peer at the naked female body. The models and their stage-set environments are fundamentally artificial and inauthentic depictions of what should be a private sphere of spirituality. The guilty pleasure of the male gaze predominates.

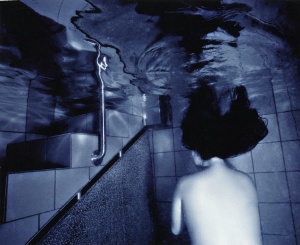

The Mikveh Project, in stark contrast, gently invades the mikveh with the photographer’s presence. Twenty photographs take us into the water itself to join Jewish women in their most intimate moments while still managing to preserve modesty and privacy. We are, via the photographer, also immersed and vulnerable. The intense physical sensation of full immersion brings with it the vulnerability of a foreign and dangerous environment.

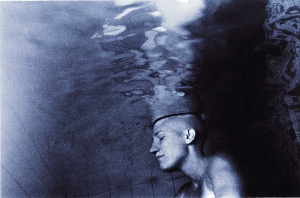

The woman with a shaved head draws us into her innermost thoughts by her intense concentration made all the more acute as the top of her head pierces the water’s surface. The edges of the photo fade just enough to give the illusion that the entire watery environment is supported by the crown of her skull. Anxiety and emotional pain seem to seethe in the water’s agitation as we ponder the narrative of her baldness.

Dark hair dramatically floats upward, reaching for the surface, as a woman crouches down facing the corner of the mikveh. Her posture is of physical concentration without shame. The downward gesture is countered by the ascending stairs and the motion of her own hair rising. This counterpoint reflects an act of submission that will lead to ascent and emergence, a feminine transfiguration from one state to another. Paradoxically physical exposure becomes a gateway for heightened spirituality.

Some of the images reflect an embryo-like floating concentration that begins to capture the elusive moment of transformation. By offering us a sense of that moment, caught in the peaceful tranquility between taking a deep breath and the effort of holding it, Rubin’s photographs evokes the vulnerability of being entirely in God’s hands, as close to the Divine as in the most passionate prayer.

Interspersed with these contemplative images are twenty equally evocative anonymous portraits of Jewish women alongside texts that explore their personal histories with the mikveh.

A seventy-six year old’s mikveh engagement party evokes the feeling that “I’m sure that in the womb that is how you feel, and we’re probably going back there. It’s like home, after you die, and we’ll feel at peace, without worry or anything.” A widow reminisces about her husband: “the first thing he always did after I went to the mikveh was touch my hand. And he told me, “You are so, so holy.” We see her hands lighting Shabbos candles.

Hands form an important visual motif in these works as agents of action and surrogates for the individual. A Jewish lesbian sought solace from her family’s rejection: “Mikveh was a turning point for me in living with my sexuality.” The images create a poetic relationship with the adjacent text. One woman recovering from a physically abusive relationship uses the mikveh as a means of healing. Her hands are gently cleaning her toenails in preparation for immersion. She ponders; “I think about the actions of different parts of my body since the last time I was there… my feet… where have my feet been? What did they run to do? It’s sort of a private Yom Kippur.” It becomes clear that for many of these women the mikveh is a unique kind of prayer, combining their feminine physicality with intense introspection and connection with the Divine.

The mikveh is a realm where the overwhelmingly sensual collides with the intensely spiritual. The ritual bath is central to a woman’s traditional Judaism with all its attendant problems, questions and challenges. Some artistic expressions, like Nimoy’s, reject the tradition for pop images in which the feminine is still locked in masculine symbols and perception. The Mikveh Project does not find the waters of the mikveh demeaning or threatening. As they refuse to be denied their spiritual heritage in a woman’s Judaism the mikveh waters can become a passage to Eden itself.

Hebrew Union Collage – Jewish Institute of Religion Museum

One West 4th Street, New York, NY