Arthur Szyk (1947) Jacob Steinhardt (1957) David Wander (2011)

The megillahs beg to be illustrated. Each is associated with a notable holiday and each presents an idiosyncratic view of Jewish history and experience. Those that are not overtly narrative cry out to be narrated while the others present the most compelling stories imaginable. Song of Songs is scandalous until tamed by rabbinic interpretation; Koheles equally assaults a pious worldview, Eichah tears our hearts out, while Esther fills us with fear and pride. And finally Ruth causes us to examine the very foundations of the Messiah. Alas, their pictorial history is uneven.

Megillas Esther is the only text to be consistently and fully illustrated, and that only since the 17th century. Selected scenes from the other texts have been sporadically depicted, notably in the 14th century French Tripartite Mahzor and the more extensive Morgan Picture Bible (1240, Paris).

The Book of Ruth is particularly compelling since it establishes the origins (problematic as they may be) of the Davidic dynasty and the ultimate Messiah. While artists over the ages have been drawn to single episodes of this narrative, multifaceted depictions of Ruth are relatively rare. I present to you three examples.

Arthur Szyk’s illustrations for the Book of Ruth was published in 1947, by the prestigious Limited Editions Club. Reflecting his florid illustrational style, his eight illustrations are pictorial embellishments that act as visual summaries rather than literal textual illustration.

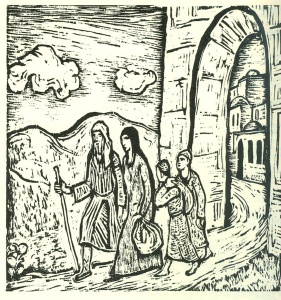

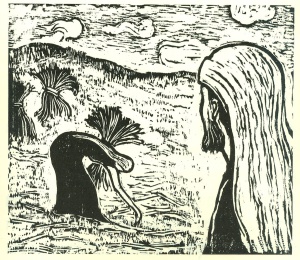

In 1957 the Jewish Publication Society published The Book of Ruth with 19 woodcuts by Jacob Steinhardt and Hebrew and English calligraphy by Franzisca Baruch. Baruch had worked with Steinhardt since their 1918 collaboration on a German/Hebrew Haggadah and is considered one of the founders of modern Israeli Hebrew calligraphy. Steinhardt (1887–1968) is a well-known Israeli painter and woodcut artist, trained in Berlin (Louis Corinth and Hermann Struck) and was associated first with the Berlin Secession group and then the Bezalel School in Jerusalem.

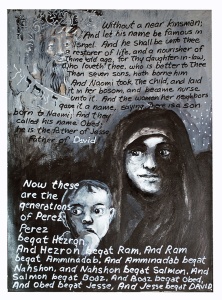

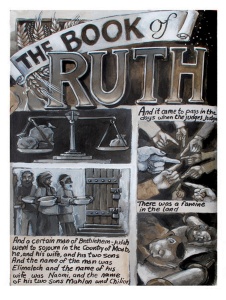

Finally David Wander has created in 2011 a scene-by-scene illustrated Megillah that sets out the entire text of Ruth, in English, accompanied by his deeply midrashic and contemporary visualizations. His Book of Ruth is but one of the 5 megillot that Wander has created in his signature art-book form over the last six years.

David Wander’s The Book of Ruth is an accordion book that measures 2’ high and 30’ long meant to fold-out right to left and done in acrylic and ink on Arches cover stock. Wander studied the text and commentaries with Professor David Kraemer, professor of Talmud and Rabbinics at the Jewish Theological Seminary during the entire process of making what amounts to a total revamping of the ancient agricultural tale.

The book of Ruth, along with Shavous itself, is deeply rooted in the agricultural setting of the barley harvest. Additionally the practice of “gleaning” or, more properly the leket, leftover stalks that had been dropped by the reapers, is narratively central to the story. Wander transforms all of these themes into 21st century metaphors for the perils of urban living. Consistently his vision of Ruth is one of social justice and the struggles of the poor widows to survive set against the unfolding of Jewish national destiny.

The 15 pages are disconcertingly read in English right to left, calculated to echo the discomfort of Naomi and Ruth’s struggle. The images are totally integrated, sometimes literally behind the words, to provide a running commentary on the plain textual meaning. The images on the first page show the townspeople locked out from the help the wealthy Elimelech should have provided, but didn’t. On page 3 the tears of Naomi’s widowed daughters-in-law anticipate the rain that the Hand of God allows to flow on the Land of Israel (1:6).

Further along we are introduced to Boaz as a prosperous frum businessman dressed in a suit as he instructs his workers in kindness to Ruth. In a sudden shift, Boaz’s blessing to Ruth (2:12) is depicted as a heavenly vision, the wings of the Holy Presence simultaneously embracing Ruth and the future vision of King David. In image after image Wander casts the Ruth narrative into the present (the barley harvest becomes many bottles of beer (!) and the leket here becomes the ‘empties’ the homeless are forced to glean from the streets to redeem for life-sustaining cash). His final haunting image is dominated by a much more biblical Ruth with the infant Obed. The child is precociously concerned, looking into the future while a lion-faced David peers out from the top of the page.

The world of Jacob Steinhardt’s Ruth could not be more different. Eleven “Biblical” woodcut images set in the Land of Israel are seen with the Hebrew text while the separate English text features generic Middle Eastern landscapes. The expressionism inherent in the woodcut format along with a masterly composition drives these images to expose the visceral core of the narrative. Elimelech, Naomi and their sons forlornly stride out of Bethlehem, oblivious to their fate. In the next image the resulting tragedy is powerfully implied in three female figures alone in a turbulent landscape alluding to the widows return from Moab. Steinhardt allows the text to inform and expand the meaning of each image, masterfully hiding one face to create a silent conversation, an internal narrative that we must fill in to comprehend the image.

The most effective example of this is Boaz watching Ruth glean in his fields. We see her stooped over in the middle distance, intent on gathering her sustenance. Only the left side of his face and back of his head are visible, forcing us to enter his thoughts about this mysterious outsider. We know from the text that he will extend his kindness and security to her, finally relating a beautiful blessing of God’s protection before offering her a full meal with his reapers. All of that emotion and dialogue flows into the silence of his gaze. Steinhardt’s most powerful images are his most spare: as he ends the Hebrew text we see a simple crown descending through the clouds to lead us to the historical and metahistorical future.

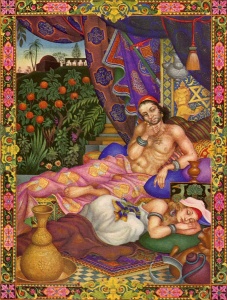

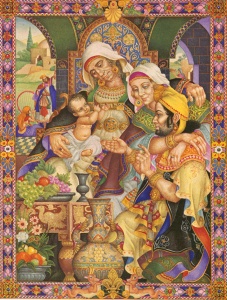

Arthur Szyk illustrated three Hebrew texts: Megillas Esther (1925 & 1950); The Haggadah (1940 & 2008, reviewed here March 2010) and Megillas Ruth (1947). All of the eight illustrations in Ruth are characteristically filled with complex details, lush Persian-style color and expressive characters. The foregrounds tend to be the most crowded and each image is framed with floral and geometric borders, adding to the surface agitation. Some of Szyk’s images have a forbidding and stern undercurrent that expresses this artist’s constant awareness of the trials and tribulations of the Jewish people and well as other injustices. His stern heraldic lions, symbolic of the House of David, are found in at least 5 of these images. In the image of Naomi, Elimelech and their two boys leaving Bethlehem the background features a dead camel preyed upon by vultures, a gruesome sign of the famine in the Land. In another odd twist, the last image of King David features the caption “ I will fear no evil for Thou are with me” from Psalm 23:4 directly over an image of the Valley of Death strewn with human bones.

Frequently Szyk is most interesting when he strays a bit from the text and delves into the internal dialogues the narrative suggests. Ruth Goes With Her Mother-in-Law presents the two women right after Ruth’s fateful decision to stay with Naomi. While Orpah is seen leaving in the background, the two women are seated, not going anywhere, and absorbed in deep reflection. Naomi is fearful, thinking of how much she has lost and how few her prospects are upon her return. In contrast, Ruth seems hopeful that something will work out.

In a similar manner the artist depicts the fateful moment that Ruth is discovered at the foot of Boaz’s bed. The text describes him as startled and puzzled as to who she was. Szyk depicts him, here seen as a young handsome man, as contemplating affection and love. In a curious way, this was Boaz’s moment of revelation. So too in Szyk’s next to last image And Ruth Becomes Wife to Boaz, the young family, Ruth, Boaz and Obed, is seen under the watchful gaze of Naomi, in spite of the textual exclusion of Ruth expressed in the verse “’There is a son born to Naomi, and they named him Obed” (4:17). Szyk is creatively amending the text to provide a sweet and lovely ending to a trying tale of widowhood and twisted fate.

Each of these artists has approached Ruth from a distinctive point of view. Steinhardt reflects the literal text, allowing it to augment his images. Szyk evokes the exotic flavor of a long-gone world as he explores non-textual meanings. Finally, Wander demands that we see the narrative primarily through contemporary eyes while allowing the sweep of the House of David and the coming Messiah to finally triumph. It’s all there and all possible in the lines of Megillas Ruth.