Medieval Echoes

Rushing in from the Boston airport on a bright Sunday morning, I breathlessly rolled into Boston College’s Gasson Hall, surprised by the sumptuous kosher lunch set out, and settled into the first of a series of PowerPoint Presentations delivered about illuminated medieval Jewish manuscripts. Within the blink of an eye, I was in heaven. This was the beginning of a two day presentation of 8 serious scholarly papers; explorations into the complexities of the medieval Hebrew manuscript. Where else but in a Jesuit college?

Graciously welcomed by James Bernauer, S. J., Director of the Center for Christian-Jewish Learning, the entire program was organized by Marc Michael Epstein (Vassar College / visiting professor Boston College) [Jewish Press, March 2012], designed to explore the Jewish image reconceived as text, Jewish iconography that could function as exegesis and the medieval manuscript as material cultural icon, a key to a polyglot culture.

Epstein set the intellectual tone by demanding that the conference hew a cutting edge; moving the focus of inquiry from manuscript as a mirror of its society to becoming a projection of medieval concepts engaging with contemporary critical academic thought. Optimally such an approach would question fundamental assumptions, especially those concerning multitudinous anomalies within many manuscripts, normally dismissed as “errors” and purely “decorative” elements.

Keynote speaker Adam S. Cohen (University of Toronto) approached the concept of “Visuality” with considerable caution, noting prevailing simplistic approaches to common medieval motifs especially those found in the manuscript margins. The innocence of scenes of dogs chasing rabbits was called into question. Complicating the pictorial analysis was the dual phenomenon of the Jewish appropriation of Christian and secular imagery and the underlying polemical relationship between the distinct but at times overlapping realms of Christian and Jewish medieval art production. The complexity of understanding many of the greatest medieval Jewish illuminations seemed to grow moment by moment.

He engaged in a renewed exploration of the very nature of one illuminated manuscript, The Bird’s Head Haggadah: its “visuality” expressed the 5 senses (2 spiritual, i.e. sight & hearing and 3 physical, i.e. touch, smell, taste). Considering the nature of the gathering it was not surprising that a quote from the controversial Profiat Duran’s Ma’aseh Ephod (1403) concluded; “One should always study from beautifully made books that have elegant script and pages and ornate adornments and bindings…. Therefore it is proper, even obligatory, to decorate the books of God.”

“Meanings In The Margins: Text And Image In The Medieval Haggadah,” presented by Abby Kornfeld (The City College Of New York) began with an examination of the Barcelona Haggadah, ca. 1370-1380, probably created in Girona, Spain. This richly illuminated manuscript displays fluid and even contradictory meanings that resonated between the core images (directly reflecting the text) and “decorative” grotesques on the margins. The important ritual of the 4 cups surfaces in recurring images of Golden Goblets that upon closer examination reveals subtle messages to be decoded. The sumptuously illuminated blessing over wine in Kiddush is crowned by a most curious image of a knight mounted on a lion thrusting with his lance at another knight mounted on a cock who bears a large golden goblet. What indeed could this curious image mean? Only upon examination of the previous page does the meaning begin to unfold. That text posits “If Shabbos falls on Yom Tov… say” this blessing. Additionally the grotesque bird mounted atop the page sternly cautions a man-dragon to keep ‘an eye out’ for such calendrical complications. The knight on the next page pointing to the golden goblet may very well be an additional reminder that the larger Shabbos goblet must be used at those times. In the space of just two pages the marginal images in relation to the text proved crucial to halachic and ritual import of the illuminated page. Who knew a crucial message lurked on the edges?

Marc Michael Epstein’s presentation continued to push the envelope to unlock the Jewish medieval political sensibility for contemporary audiences. “‘The End Of The Deed Is Implicit In The First Thought:’ Implied Ensuing Action In Medieval Manuscripts Made For Jewish Audiences” covered considerable ground from the Rylands Haggadah, the Rylands “Brother” Haggadah and, notably, a 14th c. Haggadah from Catalonia, Spain (British Library, Add. Ms 14761). In one of his first scholarly papers 27 years ago he understood the page that proclaims “We were slaves to Pharaoh in Egypt…” with the marginal image of a dog serving a hare seated in a throne as “a typical example of mondus inversus iconography wherein the ‘Egyptian Dog’ would in a time to come serve the timid but ultimately triumphant Jewish hare.” In a wide-ranging analysis Epstein now sees the visual polemic unfolding over time; the past Egyptian slavery on the bottom of the page, featuring one “sun” to dry the bricks of slavery, present medieval oppression of forced building labor, but finally capped with the eschatological hare and dog, roles reversed and basking under two “suns” (i.e. the sun and moon at the end of time).

The Leipzig Mahzor image of the “Disgrace of Haman” plays upon multiple tropes of action and consequences played out over time in the same image. Haman’s daughter attempts to disgrace Mordechai, ends up defiling her father, and falls to her death at the base of the Hanging Tree; a tree that bears more than a passing resemblance to the very “Tree of Jesse” Christianity uses to legitimize its savor. Her evil motives justly lead to the punishment of those who would harm contemporary Jews. In light of Epstein’s analysis Medieval illuminators used every pictorial and temporal resource in both the Jewish and Christian canon to give their sacred texts a cutting-edge politicization well beyond the normative piety of ritual texts.

But what about that little black bird about to be shot by a crossbow in the Cervera Bible (bifolium 444-445)? While some scholars see this as an innocent decorative courtly hunting scene, others might interpret it as an image of Jewish vulnerability in the face of Christian cruelty. According to Epstein the image is considerably more nuanced. Carefully analyzing the images, Epstein deduces that each of the threatening elements; large crossbow and predatory hawk and hunter, are in fact absurdly disproportionate and unrealistic against whatever annoyance the little bird might pose. Indeed, the image may be understood as effectively mocking the overblown Christian bluster against the Jewish population. At the end of the day, from a medieval Jewish perspective, the little bird will just fly off unharmed.

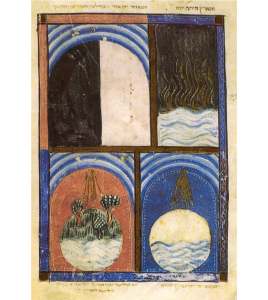

In what seemed initially transgressive, “The Iconography Of God’s Presence In Medieval Hebrew And Christian Illuminated Manuscripts,” Aleksandra Buncic (University Of Zagreb) examined what for us now are totally normative images. Buncic utilizes the Sarajevo Haggadah to identify multiple visual expressions of God’s presence. Golden rays created with actual gold leaf are used throughout the full six days of Creation, the sequence itself unique within Hebrew illuminated manuscripts. Curved golden rays represent “the Divine Presence hovered over the surface of the waters” followed by the second day with straight golden rays commanding “Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters…” Other representations of the Divine include strangely headless angels in “Jacob’s Ladder” and the Divine Hand commanding Abraham to halt the sacrifice of Isaac. Each of these motifs finds precedents or visual echoes in contemporary Christian illuminated manuscripts, indicating a refreshing fluidity between the different aspects of medieval society.

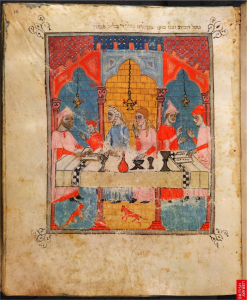

The concept of “Visuality” is obviously dependent upon looking itself. Applying this notion to the manuscripts themselves seemed especially appropriate in “The Eyes Have It: Looking At Looking In The Iberian Haggadot” by Julie A. Harris (Spertus Institute For Jewish Learning And Leadership). Visual categories proved helpful; in the Golden Haggadah: “Controlling the Gaze” operated well in both Noah’s drunkenness and in Lot’s Wife. The inability to see echoed in Jacob’s inability to “see” the deception in the sale of Joseph as well as the Plague of Darkness. In yet another image of a medieval seder (“Sister” Haggadah, BL MS Or 2884, fol. 18) we became acutely aware not only of the little symphony of hand gestures around the table but the central female figure who looks directly at the audience, forcefully pointing to the Heaven above. Here our gaze is “caught!”

The Golden Haggadah (15r) features a memorable image of six elegant Gothic maidens, depicting Miriam singing with a timbrel with the women at the Sea. The figures are significant because they serve as the transition between the Exodus narrative and the last images of contemporary medieval Passover scenes, and because they are the largest figures in the entire 56 narrative scenes in the Haggadah. However, who exactly is Miriam in this scene? Other examples of this scene clearly define Miriam with a timbrel in the center or taller than all the others. The central figure in the distinguished blue dress is playing a harp and is obscured by the woman holding up music. If Miriam is the maiden with the tambourine, it is odd that she is neither central nor distinguished by her dress. Could it be that the “hidden” nature of Miriam might reflect the Christian trope of “Synagoga,” the blindfolded symbol of the fallen Jewish nation? At the end of the session, we all felt a bit blindfolded. It was significant and refreshing that in a roomful of medieval Jewish manuscript scholars, no definitive answer was agreed upon. Not surprisingly, concrete answers are at times elusive 700 years after a complex image is created.

The second day of the conference offered continued complexity in attempts to unlock consistently difficult medieval images. Zsófia Buda (Oxford Centre For Hebrew And Jewish Studies, Yarnton /Bodleian Library, Oxford) explored “’And The Earth Did Not Cover Him:’ The Murder Of Zechariah And Its Revenge.” In the Hamburg Miscellany (1426-1430) there is a rare example of an illuminated text of Lamentations, here (fol. 1r) depicting the murder of Zachariah. The numerous textual confusions (there are three biblical Zachariahs) make decoding the image especially thorny even though it is placed beneath the Hebrew text. Further issues of “blood crying out from the earth” were explored with images of the murder of Abel, all of which lead to an examination of the motifs of martyrdom in both Christian and Jewish medieval illuminations.

Leor Jacobi (Bar Ilan University) escorted us into the heart of the Exodus narrative with “Pharaoh Alfonso, Or The French Falconer?” In the “Hispano-Moresque Haggadah” (Castile, Spain, ca. 1300) there are multiple scenes that closely follow the Exodus narrative, detailing twice when Pharaoh is depicted on horseback at the Nile River. Once he is shown with a falcon, evidently in the midst of the royal sport of hunting waterfowl and once without. In a detailed analysis of the Biblical text, images from 3 different Haggadahs and three medieval commentators, the exact meaning and import of these images was successfully decoded, directly relating the Haggadah images to contemporary images of King James I of Aragon (1213-1276) and King Alfonso X of Castile (1221-1284), both of whom practiced the royal sport of water falconry. It is clear that for medieval Spanish Jews the privileges of royal power remained remarkably constant over the ages.

“Jews And Arts In Medieval Apulia” by Linda Safran (Pontifical Institute Of Mediaeval Studies) examined some of the rare artifacts of the vibrant ancient Jewish community that occupied the heel of the Italian peninsula from the Roman era until final expulsion in 1495. Among many hints of the rich Jewish history, the record of monumental seven branched menorahs in churches that Jews “often went to admire” indicated times of peaceful coexistence in a region now almost totally bereft of Jews.

Finally, “Stars And Bones: Revisiting Ezekiel’s Visions” by Pamela Berger (Boston College) examined the multitudinous early sources of the 4 creatures mentioned in Ezekiel, finally focusing on two early 13th century Tanachs with extensive masorah micrography. Here the text of Ezekiel was illuminated by the beasts themselves in micrographic images; a celestial vision writ small with ancient tradition.

At the end of the two days a fascinating glimpse into the rich complexity of medieval Jewish life and its contemporary relevance had intriguingly emerged. This of course summoned the nagging question as to why we still do not embellish our Jewish texts with artwork at all, not to mention work of equally complex commentary.

Jews, Christians & Visuality: New Approaches

2014 Corcoran Chair International Conference: Boston College, MA

March 9-10, 2014