Making Torah Manifest: Nathan Hilu

“Man must make the Torah manifest” in every action, speech and creative act. That is clearly the credo of Nathan Hilu; master-artist of the Lower East Side, Torah, Tanach, midrash, Gemara and beyond. There is seemingly nothing that doesn’t fall within the purview of his fertile, pious and creative visual imagination. Literally everything in his creative world is seen through the lens of Torah and Jewish sensibility. We get to peek into that world in the exhilarating exhibition Nathan Hilu’s Journal: Word, Image, Memory lovingly curated by Laura Kruger, director of the HUC Museum.Through her expertise and discerning eye she has brought to our attention a rare artist within the Orthodox world: one who is as immersed in piety as in celebration of the totality of Jewish life and thought. It is clear from the 44 works in this exhibition that he is the exemplar of the very modern and contemporary American Jewish artist. And he is only 87 years young.

The “Torah manifest” text appears in How the Rabbi Ties His Shoes; a depiction of the Maggid of Mezhirech leaning over to tie his shoelaces as Aryeh Leib Sarahs comments that it is in the rebbe’s everyday conduct that he will learn the deepest meaning of Torah life. The image is primitive, direct and dominated by the text that explains Hilu’s image. While the integration of text, image and color is typical of Hilu’s approach, this is only one of many motifs that dominate his work.

The Biblical narrative is a natural for Hilu and at least 8 works here testify to that. In Pharaoh’s Dream the text of “Parsha Miketz” is detailed with Genesis 41:47-49: describing how in the “good years there was an abundance of food and Joseph gathered it in.” The bottom of the image depicts three Jews leining this parsha in shul at the bimah with the English translation surrounding them. In the top third of the image are ancient Egyptian harvesters illustrating the text. Contemporary Jewish practice, holy text and ancient history combine to create a biblical painting.

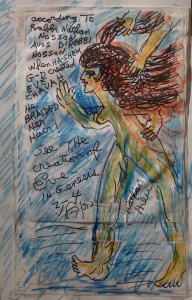

Hilu freely dips into the midrashic sensibility throughout his biblical works and a prime example is God Braiding Eve’s Hair. His simple image of a woman in profile with two hands grasping her hair from the sky is framed by the text that tells us the source is the Avos D’Rebbi Nosson. The image again demands that we consider the textual and pictorial as an equal means of Torah illumination. In Chapter 4 Rabbi Nathan celebrates the honor due to a bride and comments that the Holy One, blessed be He, did so with Eve, fixing her hair and dressing her to bring her to Adam her betrothed. I dare say no other artist has ever made an image of this concept.

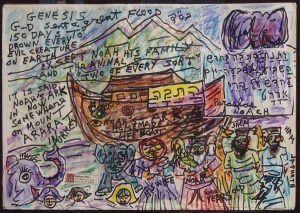

Noah and his Family reveals a good deal about Hilu’s methodology. It is clear that the original image was simply an ark floating on the water with a mountain behind it. As is the norm in Hilu’s work the English text would have to be inserted and so it was, surrounding the image. But then we see numerous cut-out additions pasted on the bottom of the original image. There are a bunch of animals and figures attached to the lower edge; Noah and his family are labeled as such. In the middle of the image the word “haTeivah” (The Ark) is slapped on the front of the ark and next to it a short quotation from Parshas Noach, Genesis 8:4, “And the ark rested in Mount Aarat,” is imposed on the now complex image. It is a pictorial summary of the terrifying travail of months of uncertain survival.

Perhaps the most evocative image within the biblical/midrashic archetype is Serach Tells Jacob. Two figures dominate the image: Serach, the daughter of Asher chosen by the shamefaced brothers to convey the news to their father Jacob that, indeed, Joseph was alive! But here the texts battle; the bottom text tells the basic midrashic story while between the figures another tale unfolds; Jacob sublimely blesses Serah with eternal life for her kindness. By what right does our patriarch exercise this power? We have no idea. And yet it becomes true! This is the textual background explicitly enumerated as the image explodes it; positing a frantic little girl playing the violin (midrashically, a harp, but who cares?), red hair flying above her flowered dress, casting musical notes at her grandfather. They are pictorially joined in the flowered patterns of both her dress and his black bechesheh; a motif that speaks volumes about the intergenerational love and respect of the Jewish family life. They are a perfect duo, both rosy cheeked and him clapping along with her as she fiddles away.

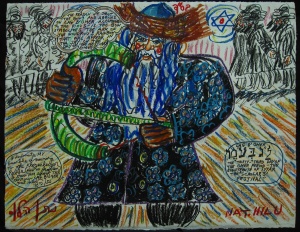

Hilu’s genre scenes depict multiple settings including “portraits” of local New York shuls including Chabad Zikron Moishe, Congregation Derech Amuno and Chasam Sopher; an exploration of his experiences as a US Army soldier at Nuremberg and Buchenwald, personal events, scenes of local Jewish life and depictions of Jewish life and lore in general. The aforementioned How the Rabbi Ties His Shoes is one such example of the latter, as well as his masterful, Lag B’Omer. On one level his image is an homage to the Klozenberger Rebbe (now in Heaven he tells us). The Rebbe stands proudly before us holding an approximation of a green bow and arrow. Surrounded by dancing Hasidim, he explains that “the reason we shoot the bows and arrows on Lag B’Omer, according to the pious, is the bow symbolizes the ark of the wondrous rainbow that will appear in the sky on the day of the Messiah’s coming.” The didactic nature of the text almost overwhelms the image but for the power and vibrancy of the color and restless line. Hilu’s passionate painterly gestures, from the sweep of the Rebbe’s burnt sienna streimel to the agitated blue beard (blue beard!), convince us that this is no primitive rendering of reality. Rather this is artistic invention at its finest in the service of a passionate belief in the vibrancy of a Torah life.

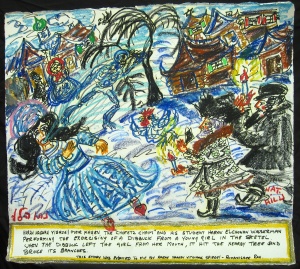

A similar theme drawn from Jewish lore is The Dybbuk illustrating a story told to Hilu by the Rumanisher Rav, HaRav Yaakov Yitzchok Spiegel. Evidently the Chofetz Chaim and his student HaRav Elchonan Wasserman performed an exorcism on a young girl. We see the two rabbis sternly approaching the girl from the right, each holding a candle. The Chofetz Chaim seems to be brandishing a rooster in addition to his siddur. The shtetl behind them tilts precipitously as does the maiden possessed. Out of her mouth a skeletal blue demon escapes in a fury. The predominantly blue nighttime tone of the image is punctuated by the red of the rabbi’s candles and hands, red shutters in the town beyond as well as a lone red bonnet of a girl watching from the background. The dynamic composition moves first from right to left and then surges diagonally to the upper right and finally returns to Miss Red Bonnet on the left, perhaps telling us that there is more than one exorcism scheduled for that night. After all, one can never tell where demons hide themselves in the human heart.

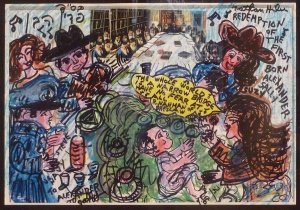

Pidyon HaBen returns us to the more mundane world of Jewish ritual celebrations. From the collaged illustration that forms the background in what appears to be the study hall of the Home of the Sages on Bialystoker Place, this simcha has all the markings of a family event on the Lower East Side. Each participant is explicitly named (Suzy, Sally, Steve, US Navy, and the baby of honor Alexander) and music, food and drinks are appropriately in evidence at the joyous redemption of the first born. But as is usual in Hilu’s art, it is the text that elevates the image to a more profound realm. In a yellow word balloon Suzy proclaims, “‘The whole world is a narrow bridge; have no fear at all.’ R Nahman of Breslaw” This initially unnerving admonition casts the whole event into another light, making us all realize both the precarious seriousness of life’s journey and the faith-based courage that will sustain us with the innocence of a child.

Artists like Nathan Hilu are easy to dismiss as merely simple folk artists. Nothing could be farther from the truth. Indeed his sophistication and insights summon the giants of Torah commentators and rival a myriad of art-world stars. The Postmodern literalism evidenced by his textual quotations is combined with a deeply poetic visual sensibility. And, shockingly, his work is potentially open to everyone by the virtue of his translations and explicit declaration of sources.

Hilu has spent his creative life making Torah values manifest in his artwork. Our Jewish lives, history and sacred texts are the medium through which he proclaims his message. It is a sacred gift; live it and make it art.

Hebrew Union Collage – Jewish Institute of Religion Museum

One West 4th Street, New York, NY