Auschwitz: A Graphic Novel by Pascal Croci

Pascal Croci’s graphic novel, Auschwitz, begins with a question to a witness from Auschwitz-Birkenau; “How long have you been keeping all this to yourself?” The answer, “Fifty-two years,” is shocking. The novel that follows provides a glimpse into the reason why these experiences are almost impossible to speak about. And in doing so Croci uncovers more than a terrible history, he points to an intolerable present.

For the Jewish artist the desire to illuminate a Torah is an irresistible act of devotion, an offering to Hashem as precious as any sacrifice imaginable. Each parsha is etched into the Jewish consciousness as a calendar for the year, changing weekly, subject, tone and atmosphere. From the primal drama of Lech Lecha to the national transformation of Yisro, and beyond to Moshe’s tragic death on the eve of our long sought homecoming, the weekly portion celebrates and delineates God’s complex relationship to His beloved. Illuminating the Torah parsha by parsha is the artist’s ultimate amidah.

Victor Majzner has created a contemporary illuminated Torah called Painting the Torah, that distills each parsha into one complex image. Majzner is a widely exhibited Australian artist and former professor of Painting at the Victoria College of the Arts who has in recent years turned his attention to Jewish themes including the Land of Israel (the Negev), the dybbuk, the Wandering Jew, creation of The Australian Hagaddah (with his son Andrew Majzner in 1993), Images of Tanya, and various projects which are connected with the Institute for Judaism and Civilization in Melbourne, Australia.

In the book’s introduction the dangers inherent in visual representations are admitted by Kabbalah scholar Rabbi Dovid Tsap. Aside from the seemingly clear ban found in the Second Commandment, according to the midrash the vision afforded the Children of Israel at Matan Torah opened the way for the creation and worship of the Golden Calf. However the Ramban “explains that the Biblical injunction refers to specific symbols only, eg. angels, celestial constellations or demonic deities, and even then only if the intention is to worship them.” In an apparent contradiction, in Avodah Zarah (43 A-B) the verse in Exodus “You shall not make [images of] what is with Me (itti) enjoins even the creation of purely decorative images. Nonetheless, the contemporary posek, Rabbi Shmuel Halevi Vozner has ruled that for the purposes of teaching Torah, even celestial imagery is permitted. What is clear is that the Torah inherently recognizes the power and danger of the visual imagination while the rabbis seem to be divided on the permissibility of visual images in practice. The long visual record of Jewish art clearly opts for its permissibility and dynamism as a cultural force.

The earliest illuminated Biblical manuscript are Christian works: the Latin Quedlinburg Itala fragment (from the book of Kings) dating around 398 CE and the Ashburnham Pentateuch, a much better preserved Latin 6th century work that features some 60 miniatures and probably reflects Jewish midrashic influence in the illustrations. The famed Greek Cotton Genesis (almost completely destroyed in a 1731 fire), was possibly produced in Alexandria, Egypt around 500 CE and was thought to have as many as 340 miniature framed paintings in the text of the book of Genesis. It may have been the original model for the extensive 13th century mosaics in San Marco, Venice. The contemporaneous Vienna Genesis with 48 surviving pages is thought to originally have 192 illustrations, many images of which show influence by various Jewish midrashic sources.

The oldest complete bible (Tanach) is the Leningrad Codex, probably written in Cairo around 930 CE. This Masoretic text following the grammatical and vocalization notation of Ben Asher contains an illuminated carpet page depicting the Tabernacle and its utensils. There are Hebrew Biblical manuscripts with carpet pages (abstract or purely decorative pages of overall illumination) from 13th century Christian Spain as well as the richly decorated 14th century Farhi Bible that sports 29 Islamic inspired carpet pages introducing the Hebrew text. Frequently the Temple implements are the favored subjects of such depictions. The medieval illuminated bibles proved irresistible to Jews and Jewish artists, created in such diverse communities as Sana’a, Yemen, Burgos, Toledo, Saragossa, Cervera, Spain, Perpignan, Aragon, and Southern Germany.

Contemporary Jewish biblical illuminations include extensive works by Marc Chagall (1935-56), Abel Pann (1930), Archie Rand’s Parsha Paintings (1989) and Yonah Weinrib (2009). That said, only Rand’s Parsha Paintings attempt to do what Majzner has accomplished, i.e. an image that sums up each and every section of the Torah.

Majzner’s images can be understood on a number of different levels. The aforementioned author of the introduction, Rabbi Tsap, sees the works as visual meditations on the Kabbalistic meanings hidden in the text. Working with the notion that the Torah operates on two primary levels; revealed narrative and concealed mysticism, he reads the meanings of the images in terms of kabbalistic color correspondences with the sefirot and refractions of emotions again emanating from the sefirot. This interpretation relies on the highly symbolic nature of many elements in Majzner’s illuminations.

In his preface Majzner sees the works he created here as a means of learning Torah, developed from six years of intensive learning and painting (preceded by some 20 years of ongoing Torah study), parsha by parsha, contemplating a wide variety of commentators, kabbalah, teachers and literature to help focus and shape his vision of the weekly portions. “Slowly the images began to reveal themselves to me. Gradually I started seeing the Torah as a visual feast.” It is deeply refreshing see an artist express this kind of humility about making art. As an expression of piety and practicality about learning Torah and creating art it is certainly a very good guide as to how the viewer should approach this work as a learning experience.

Each of the 54 parshas presents one page of highly condensed English and Hebrew text facing one image annotated with a Rashi, Rambam, Gemara or eclectic commentator. At the end of the book there is a chapter by chapter short explanation of the images. Taken as a collectivity they are deeply impressive as a learned intellectual and visual meditation on the Torah experience.

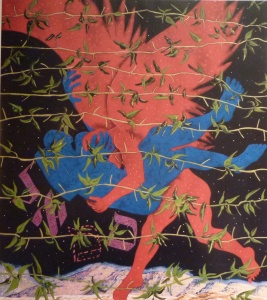

Vayishlach depicts Jacob’s terrifying encounter with a supernal being: simultaneously Esau’s guardian, the angel of death and an apparition of the Divine. The red winged creature lifts the helpless Jacob off the ground behind a vine-like scrim of foliage reminiscent of barbed wire. It is as if the crippling encounter with the supernal presaged the Holocaust.

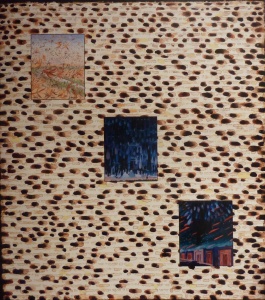

Parsha Bo waxes deeply personal, as the entire image is effectively one matzah embedded with three squares of the final plagues. The plague of locusts shows a peaceful landscape flooded with millions of insects destructively swarming in their famished quest. Next the plague of darkness seems to drip down upon the Egyptian monuments with a lava-like inevitability. Finally the plague of the Death of the First Born descends from the night sky passing over the blood stained Jewish portals, comets of red death heading to the damned Egyptian first born.

Kedoshim focuses on the fateful words; “You must be holy, since I God your God am holy.” A giant set of luchos emblazoned with the commandments forms the structure upon which the sefirot chart punctuated by blue flames effectively maps the body of the Divine. Quoting from Yedid Nefesh “Please be revealed and spread upon me, my Beloved, the shelter of Your peace” Majzner is simultaneously pleading and showing us a symbolic representation of the Divine and the road through which we can become holy: Torah and mystical revelation.

The image for Mattos reflects a midrash that depicts the encounter of Pinchas with Bilam and the five levitating Midianite kings. Pinchas overpowers them with the great holiness of the tzitz of the Cohen Gadol and the Midianite kings plunge to their deaths as B’nai Yisroel slaughter all the Midianites and burn their cities. Majzner brilliantly connects this overwhelming horror with the purging of Midianite vessels bringing this violent history into our everyday koshering experience.

The strange and puzzling mitzvah of egel arufah in Shoftim has the elders of the city declare, “Our hands have not shed this blood, and our eyes did not see.” Over the outline of the slain man indeed the bloodied innocent calf lies, the washing hands hovering, attempting to assuage the nagging guilt that somehow, somebody was responsible for an unsolved murder. Justice is demanded even from the ostensibly innocent because in the holiness of the Land of Israel we are all responsible for one another.

Majzner’s images boldly speak to us in the context of our Torah knowledge, his presentation of biblical text and commentary and a flurry of kabbalisticly inspired symbols. While much is inevitably lost in limiting his Torah commentary to only 54 visual interpretations, what is gained is the invaluable signifying of each parsha with a visual identity. We all admit that the Torah is a vast palace, a textual universe that we visit each year and yet don’t necessarily know as well as we think we should. Majzner’s illuminated Torah, Painting the Torah, if we follow him parsha by parsha, image by image, will help us get a little more personal and a take us a step closer to fully possessing our sacred heritage.

Majzner’s Illuminated Torah

Painting the Torah by Victor Majzner

Design by Michael Battista and Paper Stone Scissors

Melbourne, Austrilia, 2008