Kupferstein’s Collection

Mr. Tibor Kupferstein has a dream. He would like to create the first Jewish Art Museum in Brooklyn. It doesn’t seem too farfetched considering that the borough hosts the largest concentration of Jews in the New York metropolitan area. And yet making his personal collection of Jewish art accessible to the public has been fraught with all kinds of bureaucratic roadblocks and technical snafus that seem determined to turn a beautiful gift into a sad unfulfilled saga. It doesn’t seem fair.

Kupferstein has spent the last 30 years collecting just about anything that has a Jewish connection. Born in Hungary, he came to the United States in 1948, went to college and first became a fashion designer and then went into retail sales of fur coats. Obviously a man of many talents, he then shifted professions and finally settled into metal work contracting. The diversity and success of his professions subsequently allowed him to indulge in what became a life-long passion, collecting Judaica.

His vast collection takes up every inch of space in a two-story house on a quiet side street in Flatbush, bought just to present his collection. Each room has a general theme barely holding the massive number of works of art that threatens to overflow from room to room. One enters the house directly into the painting salon, long and reasonably well lit, with approximately 150 paintings covering every inch of the walls and neatly stacked in rows down the middle of the floor.

Just off to the left of the entranceway there is the historic Palestinian and Israeli map room that contains some 200 examples of cartography. Through the next doorway we find the home of approximately 50 rebbe paintings. Another room is jam packed with posters and photographs of Jewish comedians and movie stars. In the halls and stairways there are vintage Jewish Welfare Board posters competing for space with yet more paintings and prints.

Upstairs an entire room is devoted to all kinds of Judaica: menorahs, candlesticks, yadim both silver and wooden (one especially made for a left-handed person), commemorative and decorative plates, figurines, tourist mementos and knick-knacks. On the walls leading back to the library there are collections of 18th century Biblical prints and innumerable graphic works on yet more Jewish themes. Similarly the library is lined floor to ceiling with books of Jewish interest and a modest collection of seforim. Additionally in many storage boxes stowed away in nooks and crannies Kupferstein has managed to collect a broad selection of original letters, responsa and manuscripts from the 18th to 20th century. He even has a collection of postal stamps that concentrate on Jewish subjects.

With such a vast collection dedicated to the Jewish experience it is hard to single out which works deserve critical appraisal, but a number of items struck my eye. The 22 paintings of the contemporary Brooklyn artist Ibby Kleiner immediately drew my attention with their combination of folk artistry and deft composition. Her approach to shtetl life rises above facile sentimentality by means of her extremely astute eye for composition and visual metaphor. In Tashlich she has sensitively separated the men and women, emphasizing the women in the foreground and playing on groups of three to create a pleasing rhythm across the image. Interestingly she manages to find at least two males hidden in the women’s group, a welcome nod to the complexities of village society.

She displays similar skill in Pogrom, dividing the canvas by a low fence that separates the fleeing Jews from the deceptively benign oppressors on horseback. The Jews have only managed to snatch a few belongings stuffed in sacks before they were forced to flee. From the fact that many of the men are wearing tallism, it is subtly clear that they had to flee quickly in the middle of their morning prayers and without warning. For Kleiner disaster in the Old Country can be only moments away. In its quiet way the painting is terrifying.

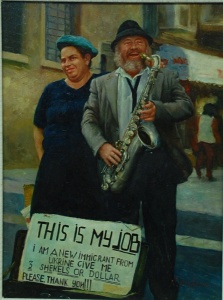

Another artist who is hard to ignore is the photo-realist N. Bingham. While it is clear that his images are painted from photographs this rather skilled painter has a good sense of composition and feel for an arresting images, especially in This is My Job, a street scene of a new immigrant musician and his wife trying to raise some cash by his performances. This artwork proves yet again how loyal Kupferstein is to anything Jewish.

Michael Gleizer’s Tashlich, a large oil on canvas, is clearly one of the showpieces in the collection. Its three-part vision of the Rosh Hashana ritual is unique in how it warps both time and space. The bottom section seems to present the scene at its most distant as the figures standing on the edge of the stream become part of the landscape. In the top band we have come closer and now see the congregation from the back, as at least two of the men have raised their prayer books in supplication. Finally the largest and central section tells us much more about this little community at the lakeside. The men are all dressed in long black coats while the children are decked out in their late summer finery; shorts, straw hats and bright outfits. Somehow the flat simple lakeside landscape with the neat white houses across the way feels closer to the Hamptons on Long Island than Poland. A truly refreshing painting.

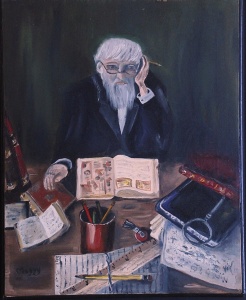

As I was getting ready to leave I noticed in Mr. Kupferstein’s office a small intriguing painting. It depicts an older man, sitting at his desk surrounded by books, papers, pencils and a ruler. He is deep in thought with his hand supporting his head. There is a wonderful combination of energy and patience in this grey haired man, a quality splendidly matched by Mr. Kupferstein himself. This kind of dedication to Jewish art and all things Jewish is an essential hallmark of the Jewish collector, a stalwart leader in the preservation and celebration of Jewish culture. Without collectors Jewish artists have virtually no way to make a living, and perhaps even more importantly, dwindling reason to continue to make Jewish art. And without Jewish art, a significant bit of Jewish life dies. We can’t let that happen. And that’s why we are truly lucky to have folks like him around.