The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League, 1936-1951

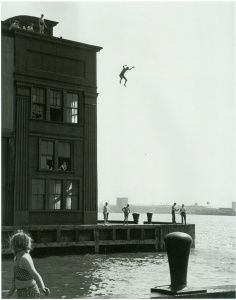

Boy Jumping into the Hudson River (1948) by Ruth Orkin reflects a tragic moment in the history of the New York photographic group, the Photo League. On the surface simply a carefree moment of urban youth, and yet dangerous. That year was the beginning of the end of a brave experiment in modern photography started only 12 years earlier. The Jewish Museum documents the efflorescence of Jewish visual creativity in photography in the current exhibition, Radical Camera, until March 23.

In 1936 the Photo League was founded in New York City by a group of young idealistic photographers, mostly Jewish and, typical of the time, many with liberal to left sympathies. “Justice, justice you shall pursue” (Deuteronomy 16:18-20) could easily have been their motto. Their goal was to promote documentary photography that would address the social issues of the day as opposed to the dominant Modernist photography that championed pure aesthetics; abstract form as pure visual stimulation.

The League became home to a group of photographers who produced some of the most significant images of their time. As social activism and progressive ideology demanded documentation, the advent of small handheld 35mm cameras in the 1920s allowed documentary photography to flourish. The League sustained itself by offering photography classes, workshops, lectures and inexpensive darkroom privileges. It sponsored numerous exhibitions of its member’s works and organized projects that explored the photographic potential of neighborhoods in New York City; including a Manhattan tenement (1936), the Bowery (1937-38), the rich and poor of Park Avenue (1937), and the Catholic Workers Movement (1939-40).

Ironically, in spite of their focus on a professed social program, they created powerful aesthetic statements that in retrospect are a major aspect of Jewish secular creativity. As the Photo League’s creation was an expression of its time, so too was its demise in 1951 at the hands of the House Committee on Un-American Activities that reflected the Red Scare starting in 1947. Brilliant essays in the catalogue, also reflected in text panels, by curators Mason Klein (Jewish Museum) and Catherine Evans (Columbus Museum of Art) and Maurice Berger, Michael Lesy and Anne Wilkes Tucker provide context and insight into the 150 images.

Orkin’s Boy Jumping is emblematic of the kind of aesthetics practiced by many in the Photo League. Patience was matched with impeccable timing and persistent observation. Their photo studio was the everyday world, the mundane of fabric of city life became a palette with which to explore life’s mysteries, joys and beauties. The bollard (a post for tying up ships) in the right foreground visually connects with the two on the pier while it simultaneously balances with the young blond girl in the left foreground. Her backward twist propels us into the heart of the image; the boy leaping and the other figures on the pier. The sheer reckless courage of leaping at least 50 feet into the Hudson River summons a daredevil ebullition of summer youth. Orkin’s composition elegantly contains the unruly joys of growing up in Manhattan in the 1930s.

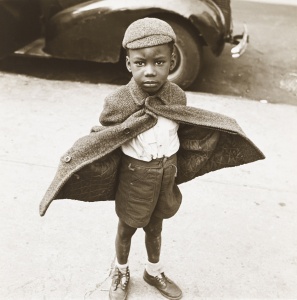

The most extensive project the League supported was the Harlem Document (1936-40), the product of a “Feature Group” guided by Aaron Siskind. It was to document a community in peril; its poverty, crime and rich social life. Among its many images taken in Harlem, Butterfly Boy by Jerome Liebling is gentle masterpiece. This young boy is seen from slightly above, emphasizing his

diminutive stature. Of course the comical gesture of holding his coat open in a wing-like motion becomes a metaphor for fleeting freedom and youth all too likely to quickly pass.

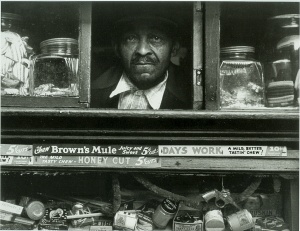

Morris Engel’s Harlem Merchant (1937) takes a radically different approach. The close, almost claustrophobic, composition emphasizes the struggle of small business owners in making a daily living.

Another neighborhood that received considerable scrutiny was the Lower East Side. Almost all of the photographers were first-generation working class and felt quite at home downtown. One unusual aspect of some ten percent of the works in the exhibition is the adoption of an aerial perspective to capture the life of the streets and to simultaneously create alluringly abstract images. Pitt Street, New York (1938) by Sidney Kerner is notable for including not only a game of stick-ball, but also profiles of adjoining tenements, their fire escapes, ladies chatting on the sidewalk and another about to go into a local kosher butcher shop. For such a spare image it is remarkable how much it tells us about downtown neighborhood life.

Harold Corsini utilizes a similar perspective to create a haunting image of street sports in Playing Football (1939), part of the Harlem Document. Here the raking sunlight creates fantastically abstract shapes of cast shadows on the street. The man caught in mid-run appears suspended as if the mere act of playing a sport allows him to levitate from the mundane reality of street life.

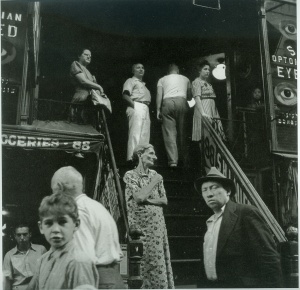

The photographers who were part of the Photo League were dedicated to every possible aspect of urban life that was going through enormous change in the 1930s and 1940s. Waves of new immigrants arrived to constantly shift the mix of race and ethnicity, creating a vibrant and shifting social scene. Sol Libsohn’s Hester Street (1945) documents this kind of flux so typical of many New York neighborhoods. Once the heart of the Jewish Lower East Side, by the 1940s the street had yielded to many other immigrants. The diversity is further reflected in that the image captures almost every person in the crowd looking in different directions, framed by dual eyes of the eyeglass shops on the right and left edges. Libsohn’s photo seems to summarize the underlying alienation amid the urban bustle.

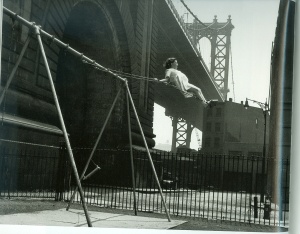

And yet amid all of the difficulties, struggles and stresses of city life, there are persistent images of hope and joy that make life ultimately worthwhile. Walter Rosenblum’s Girl on a Swing, Pitt Street, New York (1938) returns us to the unblemished joy of a summer day, to what it means to grow up in the city in the shadow of its great bridges, as Rosenblum himself did. We know the playground still exists on Cherry Street at Market Slip, thanks to the Jewish Museum’s interactive website (www.thejewishmuseum.org) that not only locates all the images on maps of Harlem, Midtown, Downtown and Coney Island, but also adds rich historical and critical material to further contextualize the exhibition’s images.

The Jewish Museum’s Radical Camera is a thrilling, beautiful exhibition that documents the development of socially conscious photography, primarily in New York City. It was a time of great challenges and great change, uptown, downtown and all around. These intensely creative, sensitive and insightful photographers all had a hand in capturing a time when New York and its people were entering the turbulent heart of the 20th century. Isn’t it interesting that the vast majority of them happened to be Jews?

Jews and Social Conscience

The Radical Camera: New York’s Photo League; 1936 – 1951

The Jewish Museum: 1109 Fifth Avenue at 92nd Street