New York: Capital of Photography at the Jewish Museum

“I think there are two kinds of photography—Jewish photography and goyish photography. If you look at modern photography, you will find, on the one hand the Weegees, the Diane Arbuses, the Robert Franks—funky photographs. And then you have the people who go out in the woods. Ansel Adams, Weston. It’s like black and white jazz.” William Klein, veteran photographer, quoted in the New Yorker May 21, 2001 by Anthony Lewis, thinks Jewishness is distinguished by a predominately urban consciousness somewhat akin to the “funky” side of “real jazz.”

The exhibition, New York: Capital of Photography, currently at the Jewish Museum, presents more than one hundred color and black and white photographs by famous and lesser known photographers, all set in New York, yet with very few of explicitly Jewish subjects. Guest curator Max Kozloff proposes the startling idea that there might be a Jewish photography that is defined not by subject but by interpretation, effectively expanding upon the pronouncement of William Klein.

Kozloff, noted art critic and former editor of Artforum, observes that in the twentieth century “the great majority of the photographers concerned [with art or street photography] were or are Jews.” He describes these Jewish photographers as “being always in transit, yet never arriving.” Further shaping the concept of the exhibition, Karen Levitov, assistant curator, maintains that “the city itself becomes a protagonist that constantly interacts with those who walk its streets” and those who photograph it.

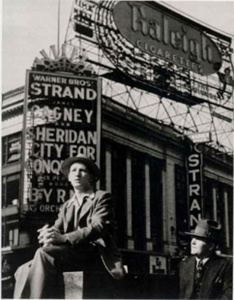

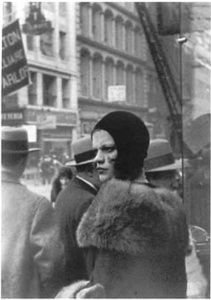

In his catalogue essay Kozloff presents examples of “Gentile photography” in contrast to expressions of a “Jewish sensibility.” Walker Evans’s Girl in Fulton Street (1930) portrays simply “a member of the urban habitat” whereas Lou Stouman’s Sitting in Front of the Strand, Times Square (1940) depicts “his subject [as] a solitary in Times Square, the world’s busiest crossroads.” Kozloff proposes that these Jewish photographers, even though they were assimilated second and third generation Americans, almost never depict their subjects as fitting in or truly belonging in the tumultuous urban environment. He sees this as reflecting the residual tensions of Jewish cultural assimilation.

The gentile photographers depict New York City as a known and accepted entity, unmindful of the undercurrents of ethnic tensions and emotions.

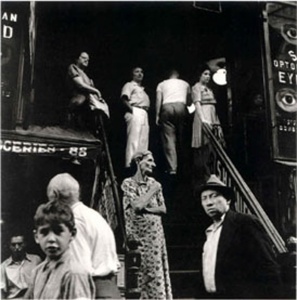

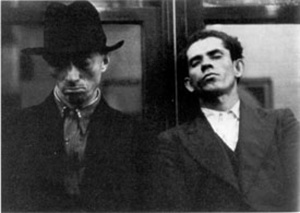

Subway Passengers (1938) by Walker Evans presents “units of population.” Evans “does not involve himself with feelings about them as people.” In contrast Sol Libsohn’s Hester Street (1938)

depicts the unstable ethnic mix of the Lower East Side in which each person is emotionally and culturally isolated in his or her own private space. The hypothesis of a special Jewish photographic sensibility is appealing. There are, however, at least two questions that must be addressed. Is this idea actually reflected in the photographs and, if so, what is specifically Jewish about this sensibility?

The assembled photographs reveal a predominance of a Jewish sensibility that finds the city and its denizens unsettled, emotional and edgy. The gritty crime photos of Weegee always have an ironic twist as some member of an anonymous crowd shoots a glance back at us. His famous Crowd at Coney Island, temperature 89 degrees… (1940) is a portrait of ethnic masses yearning for relief from the summer’s heat. In many photos the gentiles seem to be hold the grimy masses at an emotional distance; as others, whereas the Jews photograph disparate ethnics up close, threatening and familiar.

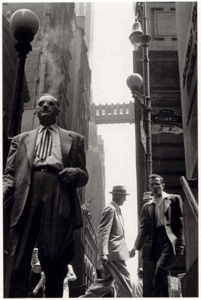

Kozloff writes; “It was as if these photographers of Jewish origin were able to comprehend a minority status that permeates the whole city as a generic condition.” If that is indeed reflected here, is it a Jewish sensibility at work or rather the overwhelming reality of ethnic New York that has impressed itself on photographers who happen to be predominately Jewish. Does the “funky” tie and subway perspective emerging from the depths in Leonard Freed’s Wall Street, New York, 1956, really connote the photographer’s Jewish vision or is this just the way New York looks?

More to the point is the need to identify a specific “Jewish sensibility.” We all believe we know when someone looks or sounds Jewish. There is a certain glance, an edge and a critical approach to the larger non-Jewish world that we associate with a Jewish ethic. But are we the only ethnic group that finds itself on the periphery peering in? Perhaps that which Kozloff calls a Jewish sensibility is generated by Jews who are losing their distinctiveness and are beginning to finally assimilate culturally. This sensibility simply reflects the loss and dislocation

from one’s tradition. Yet a more vibrant Jewish sensibility already exists in the desire to create a cohesive intellectual life founded on family and Torah. Within that context, how would a critical aesthetic driven by the study of Tanach and the analytical methodology of Gemara express itself in Jewish photography about our city?

The exhibition, New York: Capital of Photography and its catalogue essays, highlights the question of how and if Jewishness is reflected in the twentieth century photographic aesthetic. Even more importantly, by asserting the existence of a Jewish sensibility, it questions exactly what is the nature of that sensibility. This catalogue and exhibition force us to confront two possible perspectives. One is generated as Jewish photographers are moving away from Jewish life. Equally possible, though, is the emergence of a Jewish creativity driven to define and strengthen itself as a cultural force based on traditions and methodologies gathered from three thousand years of Jewish life. The future will depend on which course Jewish photographers choose.

New York: Capital of Photography

Jewish Museum

1109 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y.