Prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

The L.A Story, a selection of work from ten contemporary Los Angeles Jewish artists currently at the Hebrew Union College – Institute of Religion Museum, poses the question of what exactly does constitute Jewish Art and what is its condition today on the West Coast. As part of its answer, provided in essays by the curator, Laura Kruger and art historian Matthew Baigell, it proposes that the Jewish art presented here has some unique qualities as result of where it was produced, i.e. Los Angeles. They maintain that a commitment to Jewish values and issues, including a Jewish historical sensitivity, along with a consciousness shaped by California’s physical environment are especially evident in these diverse works of art. These issues are rightly at the vortex of an emerging consciousness in the Jewish community about the legitimacy, necessity and reality of Jewish Art.

The impetus behind this exhibition is the Jewish Artists Initiative of Southern California, an artist-run advocacy group of 24 artists fostering visual art by Jewish artists, founded by Ruth Weisberg in 2003. Of those artists approximately ten have overt Jewish content based on the works found on the group’s website. To be fair the JAI never said it promoted Jewish Art, only Jewish artists. Nonetheless, one can discern some themes of a Jewish Art from those artists that use identifiably Jewish subjects. Some motifs include Jewish history such as Ruth Weisberg’s work on Israel bound refugees on board the ill fated Altalena and Joyce Dallal’s crumpled UN resolutions; Jewish communal life as seen in much of Bill Aron’s work, specifically here in a photographic foray into the successful lives of Holocaust survivors; Holocaust as explored by Ruth Snyder and notably Terry Braunstein’s the riveting artist’s book “Shot on the Spot”; synagogue and ritual art produced by Laurie Gross; kabbalah / women considered by Gilah Hirsch; Pat Berger’s Women and their Biblical Environment series; and Jewish identity parsed by Tony Berlant and especially Eugene Yelchin’s Section 5 meditation on Jewish identity in Soviet Russia. The majority of the other artists in JAI are concerned with such diverse subjects as nature, spirituality, technology, space, Greek myths, personal discovery and enlightenment; all noble pursuits but hardly unique to Jews.

What is notably missing, with one or two exceptions, in this particular selection of artworks is the vast universe of Jewish texts, culture and history from antiquity to 1948. It is astonishing that among the hundreds of narratives found in the Hebrew Bible, Midrashim and Talmud, and the sweep of 2000 years of Jewish history across the globe only the last 50 years and its cultural preoccupations of identity and gender are fair game to make art with. It is as if the Jewish people have no worthwhile history, culture or memorable texts. Of course there is merit in focusing on the contemporary world and therefore there are works here of considerable interest, two of which I found particularly compelling.

![Jew in the Desert [detail] (1981-85), Printed metal collage; 84’ X 141” by Tony Berlant Collection of Peter Gould Jew in the Desert [detail] (1981-85), Printed metal collage; 84’ X 141” by Tony Berlant Collection of Peter Gould](https://richardmcbee.com/wp-content/uploads/2004/03/tony_Berlant_Desert_Jew-300x225.jpg)

This Jew in the desert casts a long shadow behind him three quarters of the way across the panel. His oversize head is crowned with an archaic naval commander’s hat and he is dressed in a black formal jacket, slacks and boots. While he seems rooted to the place in which he has come to rest he is likewise profoundly lost, a commander without a ship who finds himself paradoxically in the desert. The sky above him is dense with theoretical activity and structure as a few ovoids suggest luminaries. Along the horizon, just behind our lost man, is a painted wooden panel set into the collage surface depicting a picturesque desert landscape punctuated by blue mountains in the distance under a sunset tinged sky. It is very much the romantic image of the desert in stark contrast with the cacophonous reality the Jew finds himself in before us.

Berlant’s floating abstract structures summon much contemporary LA architecture, effectively echoing the work of Frank Gehry. While the landscape emerges as a kind of hodgepodge and is ultimately unintelligible to the Jew of tradition found here it has still trapped and immobilized him. Is this the fate of the Jews of Los Angeles?

Reading right to left, like Hebrew, the Jew’s past, behind him, is a singularly dense set of ten or more rectangles; white, yellow, orange, red and turquoise that are animated by vertical squiggles, virtual notations that march in a strange musical order. One could read the entire piece as a metaphor of the modern Jew’s exodus from the East into California, across the desert from the European shtetl and like the Exodus from Egypt, the idolatrous past that still beckons, structures that hint at the tabernacle that traveled with him, the confusion of his new found freedom and finally the realization that he can go no further, he is at the edge of the continent and there is no promised land to redeem him. Bleak though it is Berlant’s work here utilizes biblical references, California landscape and the specter of a cultural desert to comment on a precarious contemporary Jewish identity.

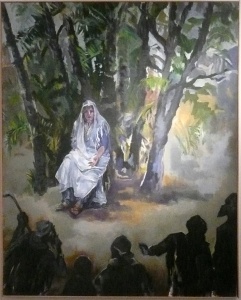

Pat Berger’s Deborah (1991) similarly works to explore our assumptions about Jewish identity. Her figure of the prophetess is depicted as a particularly contemporary woman, perhaps a portrait of one of the artist’s friends. Dressed in a fringed shawl and loose fitting overskirt, one can almost imagine jeans peeking out from under her costume. Even her sandals are suspiciously familiar. A small grove of trees frames her as she gestures towards the viewer, inviting a response to her pronouncements. Arrayed in silhouette in the foreground are five stereotypical biblical men, bearded and clad in turbans, robes and staffs. They gesture, argue and converse with each other, seemingly in wonder at this calm assured woman who presumes to judge. Pictorially they are in a different world than she is, they are the Jewish past and she is the feminist present. There does not seem to be much hope for a dialogue and this reflects a view of contemporary Jewish identity that is cut off from its origins and forced to reinvent itself in the here and now.

As insightful as this scenario may be it fails to acknowledge that we as a people have come a long way since the alienation of the modern Jew in contemporary America so typical of the mid-twentieth century. Currently all of the major movements are deeply involved in reengaging traditional texts and ritual. Openly Jewish communities are growing nationally, day school attendance is at an all time high and in the orthodox world there are more people studying Jewish texts than any time in history. Vast amounts of the traditional texts have been translated and are available to the uneducated Jewish public and while studying them the public can happily munch on an unheard of array of kosher products from almost any American supermarket. That at least is the view from the East Coast.

This trepidation with traditional Jewish subjects is surely both geographical and generational. Culturally New York and its environs have lived through the Jewish rejection of the Old World and rampant assimilation by modernity for the last 70 years. Slowly but surely the younger Jewish world is setting about to reclaim its awesome heritage, demanding that it can coexist creatively with modernity (and post modernity). There is in the last decade a sense of a new entitlement of traditional Jewish culture; Jewish music and literature in resurgence, painting exhibitions such as the recent “Scenes from the Bible” in New York (reviewed here two weeks ago) are only a few examples of a cultural swing not afraid to be too Jewish. Most importantly there is the growing promise that in this process both traditional subjects and modernity will be fundamentally transformed into a dynamic and new Jewish culture, benefiting all Jews East and West and beyond.