Considering Dura: Part II

Dura Europos looms large in the history of Jewish Art not only because of its place as the earliest example of Jewish Art but also because its achievements are seemingly at odds with the conceptual and halachic problems it presents. The complexity and variety of Torah subjects depicted are more ambitious and extensive than any Jewish Art until the advent of the illuminated Haggadahs in Spain one thousand years later.

The notion of a synagogue interior fully decorated with images does not reappear until the famous painted shuls of Poland, Lithuania and Russia in the 17th century. All that said, the images we see are at times problematic.

Aside from the fact that the extensive figuration, especially on the Western wall toward which congregants would pray, flies in the face of the injunction against graven images in the context of worship, other issues arise upon closer inspection, Many of the Torah figures, Abraham, Moses, Samuel and Elijah are depicted in Roman costume as contemporary statesmen-heroes, blurring the distinction between Jew and Gentile. There are troubling factual inconsistencies: the last two sections of the Exodus panel are out of narrative sequence; the consecration of the Temple of Aaron seems to show a bull about to be killed with an ax contrary to normative Jewish slaughter and the panel frequently labeled as Solomon’s Temple shows the Temple doors decorated with recognizable pagan figures. Finally the panel Rescuing Moses from the Nile depicts Pharaoh’s daughter as unclothed. Nonetheless, these contradictions to our notions of appropriate synagogue decoration must not distract us from attempting to understand the earliest example of Jewish narrative art.

We have seen many instances of Jewish Art borrowing non-Jewish motifs for Jewish theological purposes. The use of the Zodiac as a representation of God’s control of the natural world through his celestial agents in ancient synagogue mosaic floors, combined with figurative personification of the seasons and the inclusion of Helios, the sun god riding a chariot, was a common motif in the Jewish late antique visual lexicon. We have also seen this motif throughout Eastern European synagogues and even in the contemporary Bialystoker Shul on the Lower East Side.

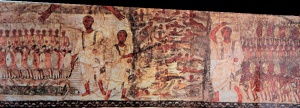

The figure of Moses, seen at least eight times, is the most frequently depicted individual in the Dura paintings. Exodus dominates the upper right register of the Western wall and reads right to left. The giant figure of Moses, his staff raised high, is leading the well-organized and armed Israelites. Behind them are the open gates of Egypt that show three winged deities above the doors, representing the paganism left behind. Next, moving to the left, is a flat aerial view of the sea filled with the drowned Egyptians. Moses appears again at the left edge of this sea, his staff stretched out over the waters. Finally Moses is seen yet again, his staff touching the sea filled with fish that has parted for the Israelite army marching along 12 clearly defined lanes. Twice along the very top of the panel the “Hand of God” is seen directing the miraculous events. The depiction of an armed Israelite Exodus going through the sea along 12 lanes indicates the artist’s familiarity with midrashim that indeed date from this period. The Exodus panel, comprising three episodes that feature a boldly heroic Moses working in tandem with an invisible God, is one of the most triumphant images imaginable of Jewish victory over pagan oppressors.

Many of the Dura stories, including Exodus, are depicted using Continuous Narrative (mentioned as “Sequential Narrative” in Part I; a technique in which the action unfolds in one continuous visual field, depicting the same characters repeatedly as events develop, thereby conflating time and space. Trajan’s Column in Rome depicts the events of the Dacian Wars in one continuous strip winding from bottom to top of the 98’ column. Completed around 131 CE, it is a well-known example of Continuous Narrative.

Directly below the Exodus panel but separated by the middle register, is the extensive depiction of Rescuing Moses. This also narrates from right to left in three distinct scenes; starting with Pharaoh ordering the midwives to kill the Jewish male infants. Progressing to the left side of the panel we see the infant Moses twice; once being held by Pharaoh’s daughter (?) in the water that flows along the entire length of the scene and then held by two women, presumably Miriam and Jocheved. They are dressed identically to the midwives and probably reflect the midrash (Shemos Rabba 1:16) that identify the midwives as in fact Miriam and Jocheved.

As one might well guess, the issue of Pharaoh’s daughter’s depiction has been hotly debated. One fascinating explanation given by biblical scholar and anthropologist Raphael Patai is that this depiction again reflects the artist’s borrowing of pagan motifs for a Jewish theological meaning. According to Patai, this figure represents no less than the Shekhina, the divine female aspect of God. As outlandish as this might seem at first, in fact at least two places in the Gemara, Shabbos 87a and Peshachim 87b posit the closeness of Moses with the Shechinah. Finally the Gemara in Sotah 12b tells us that “’She (Pharaoh’s daughter) opened it and saw him the child’ – it should have been ‘and saw.’ R. Jose b. R. Hanina said: She saw the Shechinah with him.” As Gabrielle Sed-Rajna comments on the Dura murals overall; “The free use of these materials (Tanach and midrash) shows that in the 3rd century the Biblical narrative and midrashic amplification formed an indivisible and living unity.”

On the left side of the Torah niche, effectively mirroring the Anointing of David and Rescuing Moses on the right, is the Triumph of Mordechai. The narrative flows from left to right, leading the eye directly to the Torah Niche in the center of the Western wall. Mordechai, clad in regal Persian garb is seen astride an impressive white horse being led by Haman, dressed in a skimpy tunic suitable for a stable boy, again reflecting the Midrash. Four individuals dressed in Roman togas and perhaps representing the saved Jewish people (since they are not dressed in the dominant Persian costume), seem to acclaim Mordechai’s triumph. Finally on the right King Ahasuerus is seated on his throne alongside the crowned Queen Esther. While difficult to discern, the steps to the throne are decorated with eagles and lions, another midrashic reference to the stolen Throne of Solomon used by Ahasuerus. A messenger is seen handing the king a small scroll, reflecting the royal decree allowing the Jews to defend themselves against their enemies. According to Sed-Rajna this scene is a typical “triumphal march” common to imperial Near Eastern art paired with a classic “royal audience” motif to present the contemporary Dura audience with a representation of “the providence that God generously dispenses to his people, and of the favor that a foreign ruler, and a Persian one at that, manifested towards the Jews.”

In its subtle way this panel is emblematic of the Dura narratives. The artist felt free to interpret the text to suit his immediate needs. Aside from the generous use of midrashic material, he shows the Triumph of Mordechai as if it were the climax of the story that saved the Jews. Of course it is no such thing, rather it is a fleeting victory against the determined Haman who is only defeated when Esther the next day courageously denounces him to Ahasuerus. Nonetheless the artist was determined to depict the triumph of the Jews under God’s providence using the tools of easily understood contemporary Roman and Syrian visual motifs.

Our examination of the Dura Europos murals has yielded important insights into early Jewish Art. We saw how the Torah niche images of the Menorah, Temple and Binding of Isaac utilized both symbolic and narrative representations to create meaning (in Part I). This week we examined three complex examples of Continuous Narratives, Exodus, Rescuing Moses and the Triumph of Mordechai. Exodus boldly proclaimed Jewish triumph over Egyptian oppression, Rescuing Moses depicted the salvation of the infant Moses by the hands of an Egyptian princess and finally the Triumph of Mordechai posited the victory of the Jewish people in the guise of an imperial celebration. All of the above was accomplished by freely combining Biblical and midrashic references and exploiting an eclectic assortment of non-Jewish visual sources.

In Part III we will explore the resurrection narratives of Ezekiel and Elijah along with a theory of how two broad Comparative Narratives form a scathing criticism of surrounding pagan religion.

N.B. I am deeply indebted to many of the scholars referenced in this review, especially Gabrielle Sed-Rajna’s work Ancient Jewish Art (1985) Chartwell Books, NJ and the images found therein.