Itshak Holtz Drawings

Examining a choice selection of drawings done by Itshak Holtz over 30 years ago is a rare pleasure that allows for the appreciation of his unique sensitivity and insights. I was afforded that pleasure at the inaugural exhibition of the Betzalel Gallery in Crown Heights on Thursday, May 17, 2012. Although the this modest selection of 25 drawings and watercolors of this paradigmatic frum artist ranges from 1963 to 1999, the majority of the works is from the 1970s and reveals a special aspect of his inner artistic soul. Easily this selection of images could narrate the fabric of ordinary Jewish life.

Rejoicing (1974), which at first seems so recognizable, is actually a delightful conundrum. What should be a scene from a wedding or other joyous occasion slowly reveals itself to be a much simpler image of men dancing. Both the loose nature of the artist’s line and the baggy clothing sets the piece not at a simcha but rather to be imagined as taking place in the street, a kind of spontaneous gathering and celebration. On the left there is even one individual who has not joined, his hands clasped behind his back. Strangers come together for a few moments of communal rejoicing and affirm a shared Jewishness.

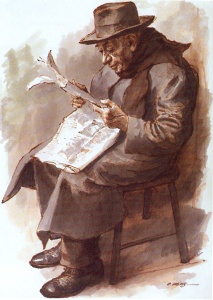

A uniquely solitary moment is captured in Keeping Up With the News (1970). This genre study takes us into the fabric of most people’s lives, the quiet moments we spend reading the newspaper. While the singular concentration of being absorbed in a story or column is something we can all relate to, the fact that this gentleman has his hat and coat on with a scarf wrapped around his neck stirs up questions of exactly where he is placed. The more I look at this drawing the more I feel the chill of an under heated apartment.

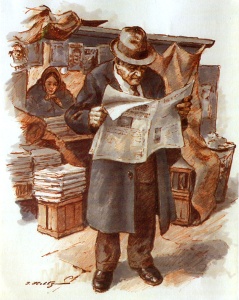

Holtz returns to the subject of newspaper reading in At the Newsstand (1971) in again a disarmingly simple image. While this warmly toned drawing seems straightforward enough, it actually captures a moment of mysterious drama. This man has just purchased a daily newspaper and after he has taken barely two steps away from the newsseller, he is for some reason compelled to stop dead in his tracks. He rips open the paper to intensely read its contents. What scenario that has unfolded we can never know: a story that affects his personal life, an explosive political event, a crucial sports score or the results of a horse race, whatever it is, we have all felt that emotion of needing to know right now.

While these emotions are not uniquely Jewish it is perhaps the passion to know, the need to seize the moment, that marks these images as reflections of our people. What is uniquely Jewish is the shtreimel. He was only 36 when he did this drawing, but seen here, these two Chasidim (1963) establish Holtz’s early commitment to depicting the orthodox Jewish world. But beyond such a commitment, this charcoal drawing is a monumental homage to the Old Masters. These two heads reflect the classical motif of two views of the same individual. The individual in the foreground is naturalistic, casual and empathetic while the profile is a more formal study, and yet refreshingly simple and clear.

Another study that demands attention is Reminiscing (1972). Again Holtz is deeply in the genre mode, minutely describing an old woman, and yet his ability to shift the focus from sentimentality to a woman deep in introspection is breathtaking. Here we are confronted with a real person, her hat slightly askew, perhaps atop an equally precarious wig. Her face has all the characteristic wrinkles of age and yet it is the lone highlight on her right lower eyelid that directs our consciousness into her inner world of memory and longing.

Perhaps the most shocking of Holtz’s drawing is also among the earliest. The Funeral (1966) depicts five Chasidim carrying a body on a bier to its grave. The grave is a gaping hole framed by two shovels stuck in the ground ready to be used to fill it in. These men do not visibly mourn. While the women behind them cry and lament, the men just carry and do their duty to the deceased. Their emotions are all interior, held in check as they do their duty, the most holy honor to the dead. The drawing captures exactly the essentials of a Jewish funeral: we honor the dead by returning them to the ground from which we all originated. We do so in quiet love, honor and respect. It is the Jewish way. Holtz has expressed the essential Jewish service. Just like that.