The Eruv and Jewish Community in New York and Beyond

What a wonderful exhibition Yeshiva University Museum has mounted with It’s a Thin Line: The Eruv and Jewish Community in New York and Beyond. Sensitively curated by Zachary Paul Levine under the watchful and expert halachic supervision of Rabbi Adam Mintz (see also his “The Brooklyn Eruv” in the Winter 2012 Hakirah Journal), the show traces the origins and development of the rabbinic construct known as the eruv based on the Oral Law.

First found in the Mishna and then elaborated in the Gemara in its own tractate, the show follows the historic development over the centuries with fascinating historic texts, urban maps, illustrated guidelines and over 130 artifacts spanning 500 years.

Initially examining European eruvim, the show quickly narrows its focus to America. The St. Louis Jewish community created the first American urban eruv in 1896 utilizing the ubiquitous telegraph wires and poles in town along with the banks of the Mississippi River. What is especially interesting is that one of the main impetuses to establishing an eruv in St. Louis was the attempt to remove the sin of public Shabbos desecration by the non-observant Jewish population. This would become a major factor in the creation of all urban eruvim.

The multiple iterations of the Manhattan Eruv is the focus of over half of this exhibition and the depiction of how the story unfolds is truly fascinating. What is striking is the rabbinic concern for Manhattan’s Jews, especially as New York quickly became the gateway and home to much of America’s Jewish population. Again the rabbinic scrutiny and action was because many of these Jews were non-observant. In 1905 Rabbi Yehoshua Seigel established the first Manhattan urban eruv, encompassing the entire East Side and utilizing the banks of the East River and the Third Avenue El. The controversy that followed lays the foundation for the next halachic battleground. Uptown migrations of Jews, halachic concerns and the demolition of the Third Avenue El starting in 1950 led to attempts to create an all-inclusive Manhattan eruv. In 1950 Rabbi Menachem Zvi Eisenstadt first proposed an eruv around the island of Manhattan based on the existing sea walls. This was finally established in 1962 in the face of fundamental opposition expressed in a 1952 teshuvah by Rabbi Moshe Feinstein. The exhibition follows the controversy as it becomes considerably more complex on both sides. It is at this juncture in the narrative that contemporary Jewish Art is introduced into the exhibition.

R. Justin Stewart’s Extruded (an eruv project), 2012, is a hanging sculpture that reflects the Manhattan eruv controversy as a three dimensional graphic. Multiple blue and white rayon upholstery threads descend from the ceiling, stopping at discrete levels to graphically depict the historically distinct Manhattan eruvim. At first it seems like a bunch of vertical lines, then the various outlines of Manhattan eruvim floating above one another emerge to create a symphony of halachic encounters. Each level represents one historical understanding of halachic repair and permission. It is thrilling to see modern rabbinics as three-dimensional art.

Elliot Malkin’s The Laser Eruv, first seen by this reviewer in Shaping Community: Poetics and Politics of the Eruv, curated by Margaret Olin this fall at Yale University is featured in an indoor version. Malkin’s work has, in its way, managed to make an ephemeral Jewish concept even more so. The possibility the laser as an eruv “wire” is still tantalizing.

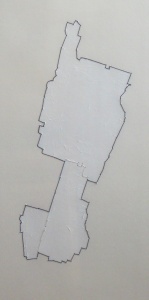

The fundamentals of eruv are outlined literally by artist Ben Schachter. First he has created an “eruv” around the two level installation created by mapping wires around the multiple and complex exhibition walls. The lines linearly depict the surrounding Manhattan cityscape as well as the specific physical outline of the Center for Jewish History, the site of the exhibition. Schachter has 5 other artworks in the exhibition, most of which compress actual eruvim into artwork maps that depict the outlines of real eruvim, here comprised of string surrounding painted enclosures. His works make the expansive concept tangible and physically graspable.

Strikingly in one display case the exhibition documents three mid-20th century arguments against any Manhattan Eruv: Rabbi Moshe Feinstein (who, while he opposes, does not condemn rabbis who would permit), Rabbi Shimon Schwab, and

Rabbi Theodore Adams. This strict halachic position is still upheld on the Lower East Side. Courageously one artist, Yona Verwer, protests. Her Tightrope (2012) prominently raises another aspect of the overall concern with the broader Jewish community. The lack of an eruv “excludes women, children and sick people from full participating in Jewish life and synagogue community.” Her installation depicts 16 panels with images of downtown communities affected by the lack of an eruv. Her artwork includes not only images from these synagogues but also community voices captured on 3 video monitors that express the pain and frustration caused by rabbinic refusal to establish an eruv on the Lower East Side. This is a powerful protest artwork on the part of observant Jews that dovetails directly into earlier rabbinic concern over Sabbath desecration by the non-observant. It demands that the eruv, introduced for the benefit of the observant, must also be understood and be created for those of our community who are in need; i.e. the vulnerable and the non-observant.

The institution of the eruv is an act of hesed, i.e. an act of love and concern. And as such, is radical and immediate. In that spirit this exhibition adds an important voice to the ongoing Eruv Dialogue in Manhattan, Brooklyn and beyond.

It’s a Thin Line: The Eruv and Jewish Community in New York and Beyond

Yeshiva University Museum – Center for Jewish History

15 West 16th Street, New York, N.Y.; (212) 294 8330

www.yumuseum.org

Jewish law prohibits carrying an object from a private domain to a public domain (or vice versa) or within a public domain on the Sabbath. One who intentionally carries, knowing the prohibition on the Sabbath is libel to the death penalty by a Jewish court. The creation of an eruv establishes, where possible, an extended private domain in which such carrying is permissible.