Hyman Bloom’s Journey

A creative life is laid out before us, how do we understand it? And since it is definitely not finished (the artist is ninety and still painting in a newly constructed studio in Nashua, New Hampshire), it is a travesty to attempt a summation. But we can certainly review what has gone before and speculate how he got to where he is now and what might come next. That is the challenge of the retrospective, Color & Ecstasy: The Art of Hyman Bloom, at the National Academy of Design until December 29, 2002.

Hyman Bloom was born in Latvia in 1913 to an Orthodox family. He, along with his parents and brother immigrated to the United States in 1920. In Boston he attended art classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and matured into an artist drawn to the contemporary avant-garde, mysticism and spiritualism of the 1930s. His connections within the avant-garde paid off when Dorothy Miller, curator at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, visited his studio in 1941 and included him in Americans 1942 at the Modern. His paintings of that era include The Bride, Rabbi, The Synagogue as well as paintings of Female Corpse and Corpse of Man. The Synagogue, purchased by the Modern in 1943, was part of the opening exhibition of the Jewish Museum in 1947.

In 1950 he is one of seven artists, including Arshile Gorky, John Marin, Jackson Pollack and Willem de Kooning to represent the United States at the Venice Biennale. By all accounts, Bloom had become an established member of the American modern art scene.

In 1954 Jackson Pollack and Willem de Kooning considered Bloom “the first Abstract Expressionist artist in America.” In 1954 he had a major retrospective at the Whitney Museum of American Art. Even though he was considered an insider, he willfully remained on the periphery of the Abstract Expressionist movement in New York and slowly drifted out of public notice and the New York art world. In the mid-1950s he did a series of paintings on séances. From 1958 until 1968 he concentrated on drawings exclusively and, after summering in Lubec, Maine on the northeastern coast, Bloom began to do more and more drawings of trees and fish. His paintings of the 1970’s and 1980’s concentrated on seascapes, fish, lurid still lifes and landscapes of the Maine woods. In 1999 he created two paintings of Rabbis with a Torah. What can we make of this wildly diverse career of making art?

Hyman Bloom has been on a metaphysical journey to locate a Jewish spirituality that was rejected long ago when he became bar mitzvah. This quest of over seventy-six years has yielded a lifetime of creative art and may now have arrived at a reexamination of that which was left behind in the old country. In his catalogue essay the Jewish scholar Matthew Baigell relates a story of when the seven year old Bloom was asked by his rebbe what he would become in America, he answered to everyone’s surprise, “a rabbi.” It of course didn’t occur, but Bloom did continue to be a deeply spiritual individual, restlessly searching out the content of the unknown throughout the course of his creative life.

In the 1930s Bloom was deeply influenced by the Jewish expressionist painter Chaim Soutine and the Catholic mystical painter, Georges Rouault. His early works have a surprising predominance of subjects that refer to his Jewish roots like The Synagogue (1940) painted when he was 27 years old. This particular painting, painted just two years after Kristallnacht, must have sent shivers up the spines of any Jew who saw it. The intense spirituality that emanates from the scene of song and prayer acts as a defiant challenge to the destruction of Jewish life already started in Europe. Its highly agitated surface, the lush handling of paint and the quivering light that affects everything from the swaying chandeliers to the ruby red Torahs summons the totality of community and Judaism as a cry of hope. The solidity and clarity of the composition affirms that the tradition Bloom has left behind is still deeply present in his consciousness.

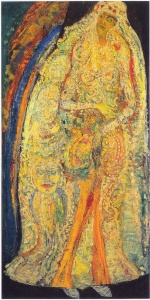

Another examination of the traditional Jewish world is The Bride (1943-1945). Her gown is a lush abstraction of pale cream, green, turquoise and red that engulfs the apprehensive maiden. Woven into the swirls of the gown are a multitude of faces and life forms, perhaps representing the myriad dead relatives that are said to attend every bride’s wedding. In this painting Bloom uncovers the emotional currents of spirituality that surround the chuppah. These were terrible years for the Jews and Bloom reflects the external reality by painting a series of corpses, male and female that he observed during autopsies and dissections he attended in Boston. These stark images reek of the Holocaust as the horrors were unveiled at the war’s end. This grim fascination with death and decay was in a way a deep rejection of the Jewish tradition of utmost respect for the dead. The paintings are expressionistic desecrations of the human form and yet they are a perverse meditation on death and the absence of the immortal soul.

A Leg (1944-1945) presents a severed limb, gangrenous and torn by untold ravages. Bloom has commented that in one aspect they represent “the corruption of society and the human spirit.” It is in this time and in the ten years that follow that Bloom is literally dissecting the world around him in a search for a spirituality that seemed to be extinguished in the ovens of Europe.

The only paintings shown from the 1990s are of two rabbis with Torahs. How did we get back here? Bloom had done some rabbi paintings in the 1940s but since then all the subjects have turned their back on the Jewish world. Now it seems to reappear in images of movement and struggle. The rabbi is ghostly pale, grasping a golden Torah. Behind him to the left is the ark with the Ten Commandments, a crown and rampant lions dominating the upper left. Opposite that image is a white presence in the upper right that the rabbi is gazing towards. The rabbi is pinned between the Torah and the ark, fixated on this whiteness that operates as a visual exit out of the painting. Has Bloom brought out the Torah again into his life? Is the search for meaning now between the glowing rabbi and his Torah and the mysterious white light, the ultimate exit? Hyman Bloom continues to paint in the determination to create visual pleasures of color and light in search of meaning and spirituality. He has served his audience well in this journey and remarks that “the artist’s reward is pleasure, ecstasy from contact with the unknown.” It is our reward too.

Color & Ecstasy: The Art of Hyman Bloom

National Academy of Design