Prints at the Philadelphia Museum of Art

What is it about big? Why are we impressed by size when we all know that the quality of any given thing is easily just as, if not more, important? The simplest answer is that while man can normally make many things that are small, i.e. on a human scale, the larger something is the more effort and skill seems to be necessary. As complexity and size increase the more similar to the Almighty’s creations does a mere mortal’s effort seem. The grand sweep of the sky, the expanse of ocean and the heights of the mountains all bring God immediately to mind. And so too is it with big artworks. Grand scale and ambition are meant to evoke power, confidence and authority; they can seem almost Divine.

The Renaissance, starting in the mid-fifteenth century, was characterized by large scale works created for private palazzos, civic palaces and newly built churches. Easily the largest and best known is Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling that measures a breathtaking 45 by 128 feet of painted surface teeming with hundreds of figures. The Venetian master Titian, who lived over 90 years and produced a prodigious number of paintings, created many impressive oil paintings for churches that measured anywhere from a modest 5 by 4 feet to a daunting 22 by 11 feet. Large scale artworks abound as the Renaissance culture throughout Europe proclaimed the glory of individual and the Catholic faith.

With the invention of the mechanical printing press using movable type in 1439, the printing of books was revolutionized and along with it the creation of reproducible woodcut prints. Engraving and etching soon followed and many Renaissance artists utilized this medium as a source of income and a lucrative way to disseminate their images and create demand for more commissions. The one problem was that images were limited by the size of the press and paper upon which the image was printed, no match for the constant demand for large images that frescos and oil paintings could create. Sometime in the beginning of the 16th century the idea took hold to make large prints using multiple blocks and plates, printed on multiple sheets of paper that were then mounted on roll paper or directly on the wall. This concept quickly caught on as a relatively inexpensive way to decorate large walls and further promote the works of the great artists that the ruling class and rising urban bourgeoisie celebrated. All of this is brilliantly documented in the exhibition at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Grand Scale, on view until April 26, 2009.

The subjects and sizes of the 47 rare examples are extremely diverse, sharing only the fact that each image was created from multiple plates and printed in multiple sheets of paper. Some examples of the prints: interior views of grand palaces, fantastic architectural facades, Christian stories, panoramic landscapes including views of Nuremberg and Venice, depictions of carved classical friezes (up to 10’ long), classical Greek and Roman myths, allegories, Customs and Fashions of the Turks (over 16’ long), a complex scene of the Large Village of Kermis with at least 115 people depicted over its 4’ length, Triumphal Procession of Maximilian I (over 8’ long), Triumph of Caesar with 65 major figures (11’ long) and finally the enormous fantasy, Triumphal Arch of Maximilian I by Albrecht Durer made from 42 woodcuts and 2 etchings measuring a monumental 11 by 10 feet.

Among this panoply of Renaissance themes there are eight Biblical subjects including Adam and Eve, The Deluge, Balaam and the Angel, two versions of the Sacrifice of Abraham, Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law and one brilliant Submersion of Pharaoh’s Army in the Red Sea. These last four woodcut block prints provide a rare view into the high Renaissance sensibility concerning the Jewish bible in the popular tradition of the graphic arts. The phenomenon of the large-scale print lasted less than one hundred years and quickly disappeared with the subsequent waning of the woodcut technique. Inherently fragile, complex and difficult to store, these are rare examples of an art that appeared for a fleeting moment in the continuum of Western cultural history. We must be especially grateful to curators Larry Silver of University of Pennsylvania and Elizabeth Wyckoff of Davis Museum, Wellesley College for their expert efforts to create this groundbreaking exhibition.

The Sacrifice of Isaac (Andrea Andreani after Domenico Beccafumi) (1586) is an example of a conflated narrative, a visual technique typical of the Middle Ages and Renaissance that presents multiple aspects of the story in one composite image. This print is dominated by the dramatic figure of Abraham ready to wield an impressive sword, his cloak billowing behind him, as Isaac, pictured as a submissive lad, awaits his fate. Of course an angel appears directly over Abraham just in time to halt the cruel deed. Beccafumi, a Sienese Mannerist, naturally felt free to take liberties with the text, notably in the fact that Isaac is not seen as bound and the slaughtering knife has become an awesome weapon of war. In the upper left background we see an angel first calling Abraham to take his son Isaac to be sacrificed while on the right Isaac is returned home by Abraham and reunited with his mother. Printed from eight woodblocks, the 29” X 60” print presents a normative version of the story with the heart-felt but non-textual homecoming as his only creative addition to the narrative.

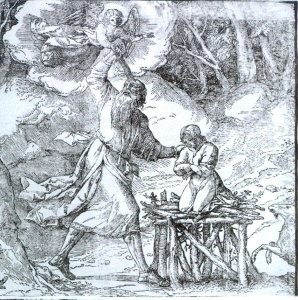

Another version of the same story is an impressive 31” X 41” print created from four woodblocks, The Sacrifice of the Patriarch Abraham, attributed to Titian (1514-1515). This is also a conflated narrative but with a simpler and more compelling progression. The foreground features Abraham charging Ishmael and Eliezar to remain with the donkey while he and his wood-laden son go up the mountain. Abraham appears in profile, a tired but energetic old man, deeply earnest as he speaks to an attentive and concerned Ishmael. Ishmael’s gesture with his empty hat initially puzzles us but serves to draw us into a complex dialogue Abraham has with his eldest son. It is a deeply compelling scene illuminating the complexities of a familial drama as they unfolded. In spite of his abundant faith and the alacrity that Abraham shows in the sacrifice scene behind them, this print convincingly begins to explain why this was indeed the greatest test of our patriarch’s life.

Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law (1590) is based on Beccafumi’s design he originally rendered in marble mosaic for the Siena Cathedral floor. It is a rather impressive 4’ X 6’ printed from eight woodblocks but considerably fussier than the stark chiaroscuro of the mosaic floor itself. Boldly composed with Moses receiving the Law at the very top of a schematic mountain the foreground is dominated by Moses holding the tablet (!) aloft ready to smash it to smithereens. He is flanked by the creation of the Golden Calf on the left and the worship of the completed idol on the right. Beccafumi’s image, filled with hordes of figures in stock classical poses (many from Michelangelo) enacting an operatic drama totally lacking all conviction and faith, is stage-set piety. Sometimes big is only that.

On the other hand Titian’s Submersion of Pharaoh’s Army in the Red Sea (1513-1516) is a masterpiece that sets its biblical drama in contemporary 15th century reality. Rendered in energetic and expressive broad strokes a brooding sky is set over the skyline of an Italian city; towers, buildings, church steeples abound with distant mountains just visible over the horizon. The seething sea comes right up to the buildings, threatening to engulf them just as it is swallowing the mounted Egyptian army in the foreground. Wave after wave advances upon the terrified riders, some advancing into the sea as others attempt to turn tail and escape the merciless waters. The chaos is explicitly rendered as the horses thrash about with their riders desperately clinging to their necks in their futile attempt to survive.

This scene of destruction is brilliantly juxtaposed with the Children of Israel seen on the right side, safe on the shore with a mountain looming directly over them portending the soon to come Sinai experience. Many react to the devastation of the Egyptian army with glee while others openly thank God for their deliverance. Most notably we see Moses, his staff stretched out over the waters, turning away from the slaughter and seeming to confer with Aaron directly next to him. This small gesture of hesitation transforms a brilliant illustration into a poignant commentary on the very nature of the Egyptian defeat, exposing the tension between the Jewish joy of freedom expressed in the Song at the Sea with the Divine admonition not to sing a full Hallel on the seventh day of Passover because, after all, God’s creatures are dying in the sea.

Easily the most exciting print in the exhibition, Titian’s print is a daunting 4’ X 7’ image printed from twelve woodblocks. Unfortunately it is also one of the least well preserved in the exhibition and especially difficult to see in reproduction. Nonetheless this dynamic original image from the pen of a master artist envisions a pivotal event of triumph tempered with compassion and creates a dazzling example of grand scale expressing insight into the complexities of the biblical narrative. And, yes, sometimes big is better.